I return once again to Homer, who says, “Sing in me, oh Muse, and through me tell the story.”

—Bob Dylan

Homer is new this morning, and perhaps nothing is as old as today’s newspaper.

—Charles Péguy

It was nary four short years ago that the incomparable songwriter Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. And notwithstanding the mercurial figure’s intriguing two-week silence before sheepishly accepting the honor, it was what Dylan said in his speech that truly surprised everyone. To be sure, Dylan credited early folk artists whose music was so “different than the radio songs [he’d] been listening to all along [because] they were more vibrant and truthful to life.” But while Dylan’s work was formed by an immersion in the folk vernacular, rhetoric, and “all the deserted roads that it traveled on,” there was something more that shaped him.

I had principles and sensibilities and an informed view of the world. And I had had that for a while. Learned it all in grammar school. Don Quixote, Ivanhoe, Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver’s Travels, Tale of Two Cities, all the rest—typical grammar school reading that gave you a way of looking at life, an understanding of human nature, and a standard to measure things by. I took all that with me when I started composing lyrics. And the themes from those books worked their way into many of my songs, either knowingly or unintentionally. I wanted to write songs unlike anything anybody ever heard, and these themes were fundamental.

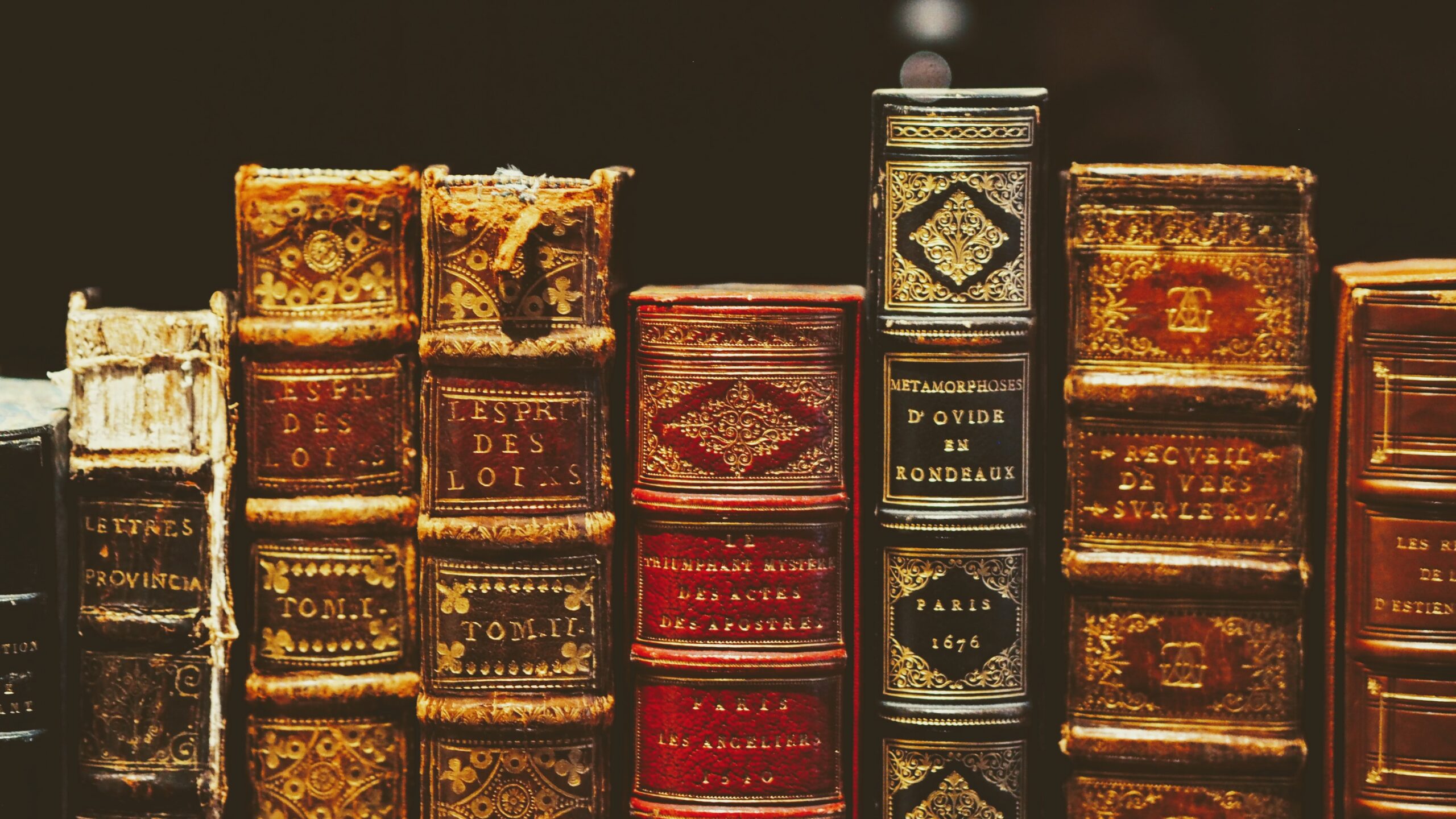

They were, indeed. Dylan would go on to explain how three classic works of literature—All Quiet on the Western Front, Moby Dick, and The Odyssey—molded his lyrical sensibility. And if you listen closely enough to Dylan’s oeuvre, you will hear strains of Shakespeare in Desolation Row, Ovid in Workingman’s Blues #2, and even Virgil in Lonesome Day Blues.

But what the Nobel Prize Committee deemed worthy of commendation four years ago is now being pulled from the curriculum in many high schools. In a recent Wall Street Journal essay, Even Homer Gets Mobbed, the #DisruptTexts and modern critical theory movement has successfully mobilized teachers and curriculum committees to remove the nefarious works of Shakespeare, Homer, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and even the troublesome Dr. Seuss from the hands of vulnerable youngsters.

Explaining the reasons for reconsidering classic literature, Padma Venkatraman, a young adult novelist, was quoted saying, “Absolving Shakespeare of responsibility by mentioning that he lived at a time when hate-ridden sentiments prevailed, risks sending a subliminal message that academic excellence outweighs hateful rhetoric.” And in an essay Weeding Out Racism’s Invisible Roots: Rethinking Children’s Classics written for School Library Journal, Venkatraman insists,

Changing the stories we read (or don’t read) won’t change society overnight, but I do believe it will help curb insidious biases from perpetuating in future generations. If we’re serious about preventing children from growing into adults who indulge in exclusionary behavior or ignore supremacist institutions and traditions, we must take small steps that are within our control, while demanding larger changes.

Further, she reasoned, “Unless we have the time, energy, attention, expertise, and ability to foster nuanced conversations in which even the shyest readers feel empowered to engage if they choose, we may hurt, not help.”

But that is exactly what teachers are supposed to do. For any formative work (whether math or physics, Spanish or literature), a teacher serves as teacher precisely because they are called to take the time and energy, to offer attention, expertise, and ability to foster nuanced conversations. That is exactly what my teachers did for me and what so many are doing for my children. We talked about the stories; we didn’t abandon them. We delved into nuance; we didn’t avoid it. When I was learning To Kill a Mockingbird in tenth-grade English, I was inspired by Atticus Finch’s courageous stance against the racial injustice leveled at Tom Robinson. And in our classroom discussion, the racial epithets in the book didn’t tempt us to use them, but further underscored the righteousness of Finch and the evil of racism. When my Literature class read The Iliad, we weren’t warmed to the idea of women being treated as spoils of war. We explored and were mesmerized by the mixed record of mankind’s heroism and brokenness. And frankly, though I was never asked to read Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, The Scarlet Letter, in high school, I think the wickedness of an earlier cancel culture might be instructive for the self-satisfied modern version.

Great literature is challenging and complex. It grapples with the muddiness of the human condition that is inescapable—a muddiness that our kids (whether we like it or not) are already wrestling with and will, in fact, be waiting for them upon their entry into “the real world,” where there will be no censors, no minders, and no trigger warnings. Great literature well taught is intended, as Matthew Arnold wrote, to reveal to us “the best that has been thought and said.” Engagement with great literature is not for the purpose of cultural snobbishness or useless pedantry, but for our deeper formation. It is to ennoble and unnerve us. It is to foster wonder and instill in us the child’s unending question, “Why?” It is to make us think. Great literature is to remind us of who we are and, even more, who we are called to be.

To be sure, the curriculum should be open to modern writers. If they write well, have a meaningful story to tell, and a valuable perspective to bring—and by this, I mean literary excellence, not thinly veiled ideological harangues—let’s consider their writing. Perhaps their work too will one day be considered a classic.

But in the meantime, don’t cancel Homer. Let’s celebrate literary masterpieces in their wonder and grittiness. Let us learn well their virtues and grapple with their vices, for they are human virtues, human vices, that must inevitably be grappled with regardless how careful a curriculum. In this lies the process of formation; in this is the molding of character. And to all the teachers and mentors who did this for me (and for my children), thank you and please carry on.

After all, you just never know who you may be forming.

Just ask Bob Dylan.