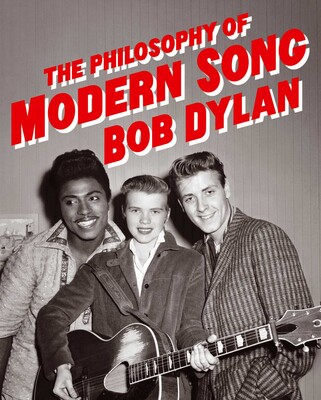

Over sixty years into his career, Bob Dylan remains a prolific artist, resuming his Never Ending Tour after a brief pause due to Covid and building upon his already tremendous body of work with new, provocative material. The latest installment is his book The Philosophy of Modern Song, released in November. The book is not a systematic treatise, as its title might suggest, but rather a series of vignettes of about sixty-six songs chosen from almost every decade of the last century. The majority of the songs covered in the book were recorded in the 1950s and early 1960s as Dylan grew up and came of age. The text exudes classic Dylan: dense imagery, symbolic, abstract, hard to follow, charming, vexing, and full of rich insight. There appears to be no central theme to this book; it reads more like a journal that Dylan fills with thoughts and responses in real time as he listens to each song. It exemplifies what the Anglo-Catholic T.S. Eliot describes in his essay on artists called “Tradition and the Individual Talent”: “The poet’s mind is in fact a receptacle for seizing and storing up numberless feelings, phrases, images, which remain there until all the particles which can unite to form a new compound are present together.”

There have been some intriguing albeit unsubstantiated claims that Dylan recently converted to Catholicism. That a Christian sensibility has been occupying his mind, however, is very possible: during a run of dates last spring, Dylan concluded every set with “Every Grain of Sand,” one of his biggest hits during his period of writing Christian music. The Philosophy of Modern Song further suggests that he is indulging that sensibility because it is deeply rooted in Christian culture.

It is at least noteworthy, even if it is only pure coincidence, that there are sixty-six chapters, the same as the number of books in a Protestant Bible, and the book is replete with references to Catholicism and Scripture, some more serious and some more flippant. In the chapter on “Mack the Knife” by Bobby Darin, Dylan writes, “Whereas Sinatra just about invented the Roman Catholic Church, Darin was merely an altar boy.” Concerning “Ruby, Are You Mad?” by the Osborne Brothers, he calls the song “Church Latin.” He references the archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael while exploring “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” by Nina Simone. In his piece on “El Paso” by Marty Robbins, Dylan searches for metaphors in cassocks, bishops’ rings, early Christian martyrs, the Vatican, and the Eucharist:

Rosa’s Cantina is the same cantina over and over again. The symbolic Rosa, the black gown and the bishop’s ring, the bread and the wine, and the blood. The blood of Christian martyrs, blood that dies the white rose red, racked and scourged. A Catholic song, universal, where no insult will go unchallenged. Where every trail goes cold, where Rome has spoken.

It has long been argued that Dylan’s music cannot be understood without a deep knowledge of the Bible, and the same is true for the music that Dylan reveres. He compares the principal character in “Long Tall Sally” by Little Richard to the Nephilim people in the Pentateuch, and he ponders the pagan god Moloch that appears throughout the Old Testament in the chapter on “El Paso.” The protagonist in “Blue Bayou” by Roy Orbison encounters “the Tower of Babel . . . skyscrapers of gibberish and double talk.”

One of the reasons people turn away from God is because religion is no longer in the fabric of their lives.

One of the most unexpected passages in the whole book appears in the chapter on “If You Don’t Know Me by Now” by Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes, when Dylan ends the chapter with a reflection on the book of Job, which reveals not only his grasp of Scripture but also some familiarity with biblical scholarship:

Supposedly, early readers of the Bible were disturbed by the harshness of God’s behavior against Job, but the prologue with God’s wager with Satan about Job’s piety in the face of continued testing, added later, makes it one of the most exciting and inspirational books of the Old or New Testament.

Many songs Dylan explores clearly signify elements of Christianity, and for good reason: most of these songs were created in a world that was Christian socially, morally, and cultically. Up through the revolutions of the 1960s, elements of Christendom permeated the wider Western culture and held strong influence in the arts. This holds true in most music genres of the time, the same genres that hold Dylan’s attention in this book: blues, country, folk, bluegrass, jazz, and early rock and roll. Dylan puts it this way in the same chapter on “If You Don’t Know Me by Now”:

One of the reasons people turn away from God is because religion is no longer in the fabric of their lives. It is presented as a thing that must be journeyed to as a chore—it’s Sunday, we have to go to church. Or, it is used as a weapon of threat by political nutjobs on either side of every argument. But religion used to be in the water we drank, the air we breathed. Songs of praise were as spine-tingling as, and in truth the basis of, songs of carnality. Miracles illuminated behavior and weren’t just spectacle.

Part of Dylan’s philosophy, it seems, is more than mere nostalgia. We have forgotten the musical traditions that form the bedrock of our music, and we need to return to them. If we heed his words, we will find that those traditions matured in a Christian culture. The very roots of the music we find all around us bring us face to face with an ethos of worship, praise, and petition woven in “the fabric of their lives.” The Philosophy of Modern Song, then, has a very timely appearance. In the prime of the streaming era, Bob Dylan chooses to engage in ressourcement, inviting us present-day readers to discover what our musical precursors can teach, and their pedagogy is rife with seeds of the Word.