At his concert on May 17th, 1966, Bob Dylan was a lightning rod. Some of his fans were outraged. They’d heard that he was bringing an electronic guitar on stage during his recent concerts, a shocking departure from his folk music roots. Would electric Dylan grapple with social issues and speak to people as soulfully as acoustic Dylan?

Then came a moment that changed rock music forever. More importantly, it changed Dylan.

Shortly after 7:30 p.m., Dylan walks onto the stage of the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, England. In front of 2,000 fans he plays a solo set with his acoustic guitar and harmonica. The crowd swoons.

After he finishes Mr. Tambourine Man, he walks off the stage. The audience is on edge as they wait for the second set. They’ve heard rumors that it might be electronic rock.

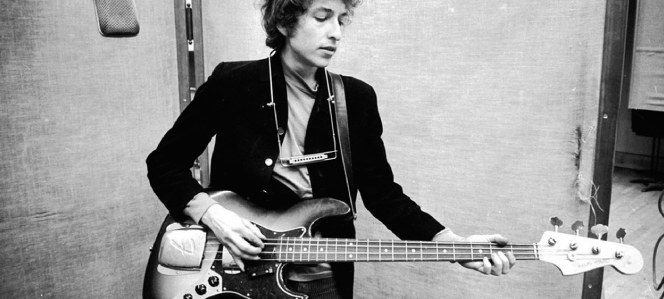

When he comes back on stage with his band, the Hawks, he’s got a 1965 black Fender Telecaster electric guitar with a maplecap neck swinging from his neck. Rick Danko, the bassist, has a Fender Jazz Bass plugged in to a Traynor amplifier. Dylan is about to blow them away with high decibel sound.

Tension builds in the crowd. Hecklers rumble. By the time he finishes the song I Don’t Believe You, Dylan is straining to be heard over the speakers. Fan C.P. Lee remembers the thunderous volume: “I felt like I was being forced back in my seat, like being in a jet when it takes off.”

Then things turn nasty. After Ballad of a Thin Man comes to an end, one fan, a non-believer in Dylan’s evolution, finds a rare moment of quiet and cries out “Judas!”

In the history of heckling, this stands apart. It’s the accusation that one is a traitor, not true to oneself, and not true to one’s friends—or fans. The only thing worse is the rebuke of Peter: to be called “Satan.” Neither one is good.

Dylan strums his electric guitar and grumbles, “I don’t believe you.” He starts plucking the strings of his Fender. “You’re a liar!” Then he turns his back, turns up the volume, and delivers a thunderous version of Like a Rolling Stone. When he sings the line, “How does it feel?” it sounds like an accusation, not a question. His whole body writhes, and he pours what’s left of his voice into his microphone as if he wants it to climb down his heckler’s throat.

Dylan knew himself.

When he heard a voice call him “Judas”, he knew it wasn’t the voice of someone who truly knew him. It wasn’t the voice that called him from the beginning.

Dylan knew the lie because he knew his story.

The Story of Stories

Bob Dylan is a master storyteller. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature for his songwriting in 2016. But before he told stories through his music, he listened to his own story. Because he did this, he understood his personal evolution, even if others didn’t.

Dylan also listened to our human story, which is caught up in a divine drama of creation, rebellion, redemption, and restoration. He didn’t learn about it as a third-person observer, but as someone caught up in the drama.

The story was not only about him, he was an actor in it. Knowing the story allowed him to make sense of his life and the events unfolding in the world–the Cold War, the Space Race, the Civil Rights Movement–because he knew the plot.

Dylan’s writing reveals the extent to which he assimilated the Christian narrative into his life. In his early years in Greenwich Village, the American Civil War fascinated him. But he didn’t see it merely as the bloody, mindless death of 750,000 people. In his memoir he writes, “Back there, America was put on the cross, died, and was resurrected. There was nothing synthetic about it. The godawful truth of that would be the all-encompassing template behind everything that I would write.”

He didn’t learn the godawful truth about human nature from the Civil War. He learned it from the bible. He saw life, death, and resurrection happening all around him because he knew the universal story of salvation.

According to the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, the mark of postmodernism is “incredulity toward metanarratives,” or a refusal to accept the story that we’re all immersed in. Dylan, the most modern of men, didn’t adopt this incredulity. Instead, he rooted himself in our human story and the personal stories of the people around him—stories bound together with timeless truths. Because he did this, he was able to make some of the most powerful music of the 20th century.

We can learn from him.

Story-Driven Discernment

God can break into our lives and change our trajectory in a heartbeat. But he never destroys our history. He redeems it.

Dylan knew that his musical evolution was true to himself because he didn’t view events in his life in an atomistic way. He didn’t adopt a “hermeneutic of discontinuity” which does away with the past. Pope Benedict XVI often spoke about the dangers of this hermeneutic, or way of interpretation, when speaking about the Church’s liturgy. Instead, he says that a hermeneutic of “reform” must be seen within a hermeneutic of continuity.

And so with life. Dylan understood his evolution as an artist through the whole of his life.

Am I not sometimes guilty of thinking of vocational discernment only in terms of the future? In terms of what God is calling me toward? No doubt God is calling me toward something, but He has been calling me from before I was born! If he hadn’t, I wouldn’t have been born. To ignore that reality is to ignore the story of God’s love for me.

It’s only if I take my entire story seriously that I can understand and find meaning in the present, and this brings an entirely new depth to vocational discernment.

But it’s not only my story that matters. The people that I encounter in my daily life have personal stories that deserve to be listened to. It’s an act of love to enter deeply into their stories with empathy, imitating the love of God who entered into mine. Looking at another with an empathetic gaze that says, “I’m here, I care about your story,” has the power to awaken and make present a story that brings light and life to us both as we witness the work of the Holy Spirit who was present from the beginning.

Often, the “shape” of God’s call can only be discerned after we’ve stepped back and looked at the entire canvas. And we can do this by entering into one another’s stories.

The life of each person can’t be understood in a snapshot, a resume, or a social media profile. We have to enter fully into one another’s stories if we hope to know and love them as God does. He is the archégos (ἀρχηγός)–the Author –of every human life (Acts 3:15).

And God is an author worth reading.