Bishop Robert Barron has lately mentioned that we in the United States appear to be experiencing a “Jacobin moment.” Legitimate grievances about justice in the civil arenas have given way to unruly, sometimes violent mobs running hot in our cities, and contentious debate within the Church.

But this is not the only “Jacobin moment” in recent history. In fact, on a global scale, 2020 may change things forever, but it is still something of a little sister to the tumultuous year of 1968, a watershed year, which ushered in an era of social disintegration unique in living memory.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, setting off riots in many cities and sparking urban unrest that would last for months. The following month in France, agitators almost brought down the government. On June 6, Democratic presidential candidate and senator Robert Kennedy died from wounds suffered after an assassination attempt the day before. In August, Soviet troops brutally crushed the “Prague Spring” in Czechoslovakia, and Mayor Daly put down the infamous “police riots” at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The Vietnam War got worse by the day. The list goes on and on. In the United States it all gave way to 2,500 domestic terrorist bombings in 1971 and 1972—an almost unfathomable situation even for the wild year we are now experiencing.

Importantly, where we are now comes from where we were then, and the clash of ideologies that seems purely political is really a contrast of religions. Author Joseph Bottum said recently,

What I’ve seen for some years building and is now taking to the streets once again is the fourth Great Awakening except without the Christianity. I see in other words what’s happening out there as spiritual anxiety. But spiritual anxiety occurring in a world in which these people have no answer. They just have outrage. And it’s an escalating outrage.

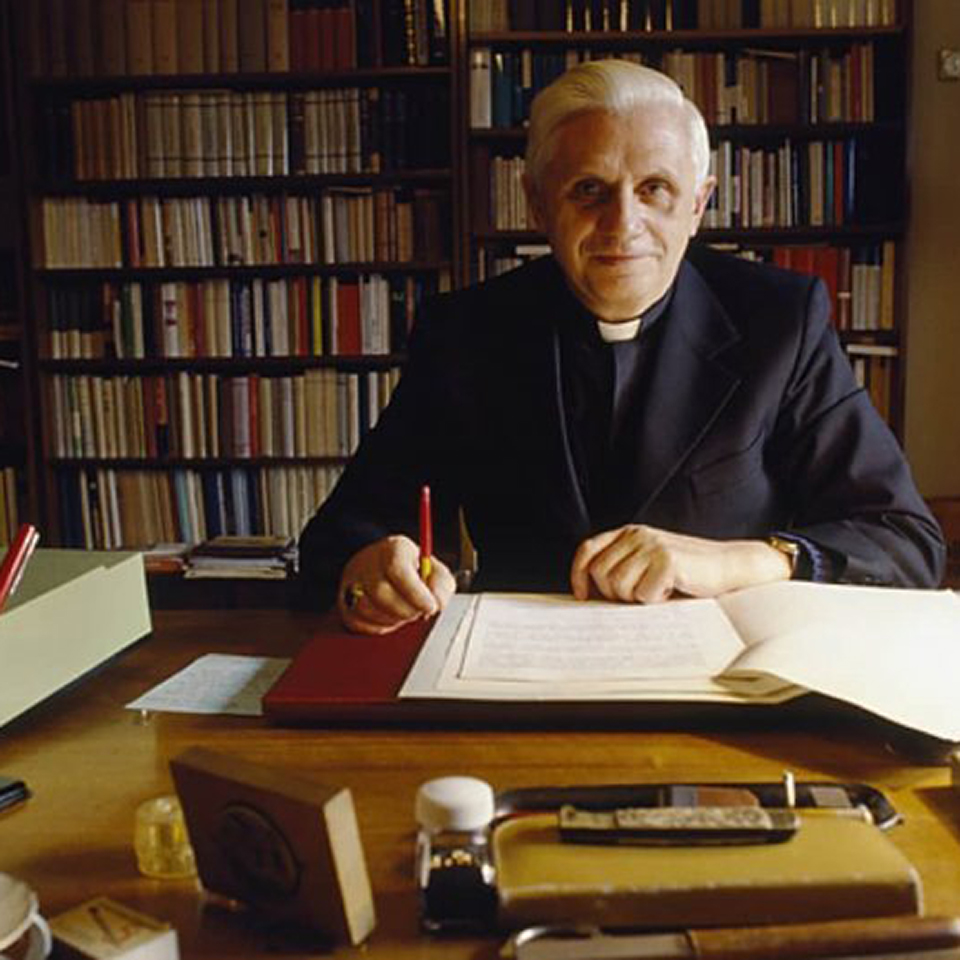

In his theological masterpiece Introduction to Christianity, Joseph Ratzinger foresaw it all, and offered a way forward that is still largely untried. In the preface to the new edition of 2000, Cardinal Ratzinger wrote:

The year 1968 marked the rebellion of a new generation, which not only considered postwar reconstruction in Europe as inadequate, full of injustice, full of selfishness and greed, but also viewed the entire course of history since the triumph of Christianity as a mistake and a failure.

In the midst of social turmoil, Ratzinger wrote, the job of the Church was to propose Christianity anew, and with evangelical bravery. What if we could think of the people pulling down sacred statues as potential recipients instead of enemies of the Gospel? The future pope begins, “In the leaden loneliness of a God-forsaken world, in its interior boredom, the search for mysticism, for any sort of contact with the divine, has sprung up anew.”

It forces us to wonder: Are even the protestors vandalizing sacred things somehow looking for God? Of course they are. But how do we respond? Ratzinger ponders, “Need we only call on the aggiornamento, take off our makeup, and don the mufti of a secular vocabulary or a demythologized Christianity in order to make everything all right?”

No. The project is far more startling.

James Marsh’s 2008 documentary Man on Wire is based on the memoir of the famous French tightrope walker and daredevil, Philippe Petit. On August 8, 1974, Petit attempted his greatest feat ever. With a small band of accomplices, Petit broke into the World Trade Center, which was then in the final stages of construction, and flung a wire from one tower to the other. He then stepped out into the sky and walked for forty-five minutes above New York City, holding a thirty-foot long, fifty-five-pound balancing pole. He looked down all 1,776 feet and waved at the tiny specs of people below. At one point, he even laid down on the wire and looked up at the sky. If you haven’t seen it, I promise, you’ve never seen anything like it.

Petit demonstrated a fearlessness that seems insane to the normal person. Who can imagine being that confident in the face of anything even remotely so perilous?

Here, Christians can draw inspiration.

We begin by admitting our precariousness on our own tightrope. Let’s face it, doubt about the truths of Christianity’s claims will at least occasionally haunt even the most ardent believer, so why pretend otherwise? We face the dilemma that “what is at stake is the whole structure; it is a question of all or nothing.”

But the inverse is also true. The avowed non-Christian religion of both nonviolent and violent strands of secularism and social activism are equally as vulnerable. If there is even the slightest doubt in the non-Christian mind that the reality of the faith is true, then, Ratzinger argues, “that ‘perhaps’ is the unavoidable temptation it cannot elude, the temptation in which it, too, in the very act of rejection, has to experience the unrejectability of belief” (p. 46).

At any moment, misguided zeal that leads to destroying a statue of a saint or vandalizing a Church could turn around and transform miscreants into the most reluctant converts in all of America. Think of Saul of Tarsus, onetime persecutor of the Church. If Christians can keep the “perhaps” alive and well, then we keep the trap of reality expressed in Catholic doctrine ready to spring. An ardent believer in something—anything!—runs the risk at any moment of falling off the tightrope and into the pit of reality: God, creation, Christ, the Church.

Despite the strategy of “doubt” and “perhaps,” the faith of the convert-catchers must be mature—none of what Bishop Barron calls “beige Catholicism” or what Ratzinger calls “an interpretation of Christianity . . . that no longer offends anybody.”

Nor can Christians wallow in victimhood, whether real or imagined. “Belief,” Ratzinger says, “has always had something of an adventurous break or leap about it.” Or as Chesterton put it more than a decade before he made the leap into the Catholic Church, “There never was anything so perilous or so exciting as orthodoxy.” We need fearless saints to walk the wire, with the ability to lie down and stare up to heaven and look down to the world and not fall.

In a stroke of genius, the future Pontifex showed us how to build a bridge from Christian reality to non-Christian artifice against the backdrop of postmodernity’s own worldview. Ratzinger notes, “Both the believer and the unbeliever share, each in his own way, doubt and belief.” He concludes, “Doubt, which saves both sides from being shut up in their own worlds, could become the avenue of communication.”

The next time we see a shocking image of a saint tumbling down—or a beheaded Mother of God—once we have processed our justified anger and sadness, let’s see how we can “resurrect” them; let’s offer up a prayer to the God who resides even within every action of doubt, that he will fill it, and to overflowing.

Then let’s expect to see a stirring of grace replace the tumult.