The Mysterious Benedict Society, now airing on Disney+, is a refreshingly subversive adventure story. Based on the book series by the Arkansas novelist Trenton Lee Stewart, The Mysterious Benedict Society places children at a level of importance rivaling Jesus’ words in Matthew’s Gospel: “Unless you change and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” The children who make up the mysterious society are four brilliant and talented orphans, led by Reynie Muldoon, who is played by Mystic Inscho. Young George “Sticky” Washington has a photographic memory; Kate Wetherall has endless practical knowledge and physical prowess; and Constance Contraire, played by the hilarious young Russian actress Marta Kessler, appears to be telepathic.

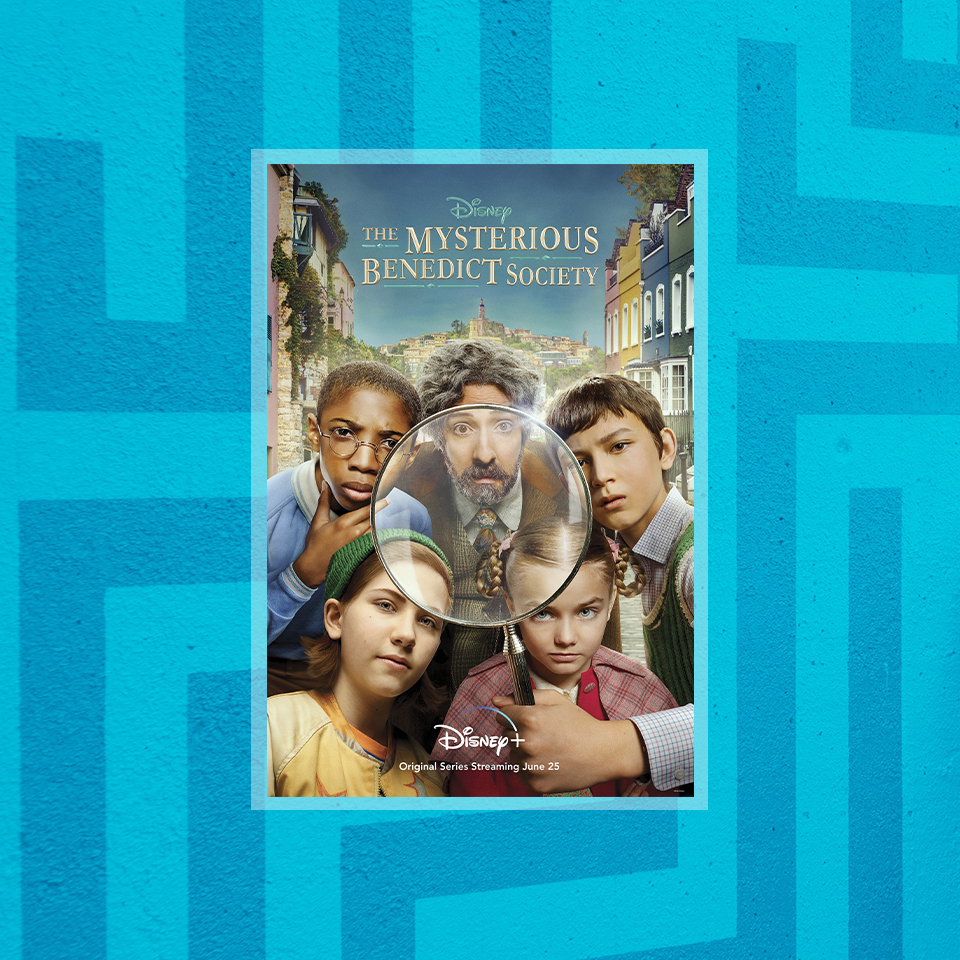

Tony Hale produces the show and stars as the mysterious Mr. Benedict, who finds the four children and prepares them for a special mission, telling them, “You all possess a quality that is lacking in our society.” Benedict is a kindly, rumpled intellectual—an orphan himself who seeks to save the world from “the Emergency,” a mind-control campaign being waged through subliminal messages in the media. He lives in a remote, beautifully wooded landscape, surrounded by books, drinking tea and eating earthy meals with his eccentric associates, including the superb Kristen Schaal as Number Two.

Like a loving father, Benedict is noncoercive and noncompetitive to a fault, creating a refuge from the world’s manipulations. He says, “There is a place where truth matters, even if most people don’t pay attention to it.” In either an uncanny coincidence of names or an unacknowledged common source in the work of Alasdair MacIntyre, The Mysterious Benedict Society evokes something like the “Benedict Option,” the prescription for renewing civilization that Rod Dreher describes in his well-known 2017 book.

The Mysterious Benedict Society takes place in a mechanical rather than digital world, with welcome echoes of Roald Dahl, Madeleine L’Engle, and Lemony Snicket. It feels like the past, but not any real past; and the characters, plot, and overall aesthetic convey the same humane analog reality present in most of the films of Wes Anderson. There are no cell phones or personal computers. No polyester or disposable dinnerware. The children must even use Morse Code as part of their mission to expose “The Emergency,” which we quickly discover is coming from The Institute, a school for gifted children. Reynie, Sticky, Kate, and Constance infiltrate the school in order to report back to Benedict with information that may be helpful in stopping the wicked designs of the Institute’s unknown leader. The Institute’s bright yellows and blues, along with a somewhat more modern design than the rest of the show’s setting, contrast with the endearing rag-tag flock that the tweedy Mr. Benedict shepherds. When we finally meet the Institute’s headmaster, Mr. Ledroptha Curtain, we find him and his world to be the mirror opposite of Benedict’s: intimidating, antagonistic, and “progressive.” (I’ll avoid spoilers here and leave it at that!) The children are encouraged to watch satellite television whenever they like and to eat whenever they are hungry. They are given constant mixed messages to go wherever they want, so long as they stay on the trodden paths. The Institute is a place of jargon and aporia where there are no rules but lots of strict, unspoken standards. As we see in our own world, the penalty for nonconformity in an ostensibly laissez-faire environment can be severe.

The Mysterious Benedict Society is timely. In a way similar to Dahl’s Willy Wonka, Benedict is forthright about wanting to use the four genius orphan children, if they are willing, as a foil to the powers-that-be who are corrupting all children in myriad ways. Reynie, Sticky, Kate, and Constance represent something like Dumbledore’s Army from the Harry Potter books, and they embody innocence and loyalty in a world where, Benedict tells them, “proof is useless unless it’s proof of something people already want to believe.” The tragedy of “my truth and your truth,” “truthiness,” and “fake news” almost seems normal now; but recent events have intensified unease in many of us like we have never felt before. Someone is manipulating us . . . but who? And why? If it turned out that 5G really was a massive brainwashing operation, would anyone really be surprised? But more startlingly, would anyone really care? The Mysterious Benedict Society encourages us to wake up.

Even in these strange days, kids tend to call things as they see them. Reynie sees right through Mr. Curtain’s encouragement to “work the system.” Kids know when they are being manipulated, and they do not like it. They turn away when an abstraction clashes with the concrete reality they are experiencing in the moment (try to tell a three-year-old to save something she is enjoying now for some indeterminate time in the future instead). And becoming like children, Jesus says, is essentially about humility and courage.

The first few episodes of The Mysterious Benedict Society remind us that if we do not succeed in ruining our kids in this generation, it may well still be possible for them to make something better of this world than our current technocratic paradigm. God willing, the future could even look a little bit like Mr. Benedict’s life of inquiry and recreation, and like Christ’s life of worthy devotion. Or maybe some of us should invest in tweed and try a Benedict Option with whoever wants to come along. Just no cell phones, please.

If you have read the books and know the ending already, please don’t tell me. As I write this, Episode 5 of 8 is about to debut on Disney+, but I am unable to wrest the first novel from my daughter’s hand. The Mysterious Benedict Society concludes on August 6, 2021.