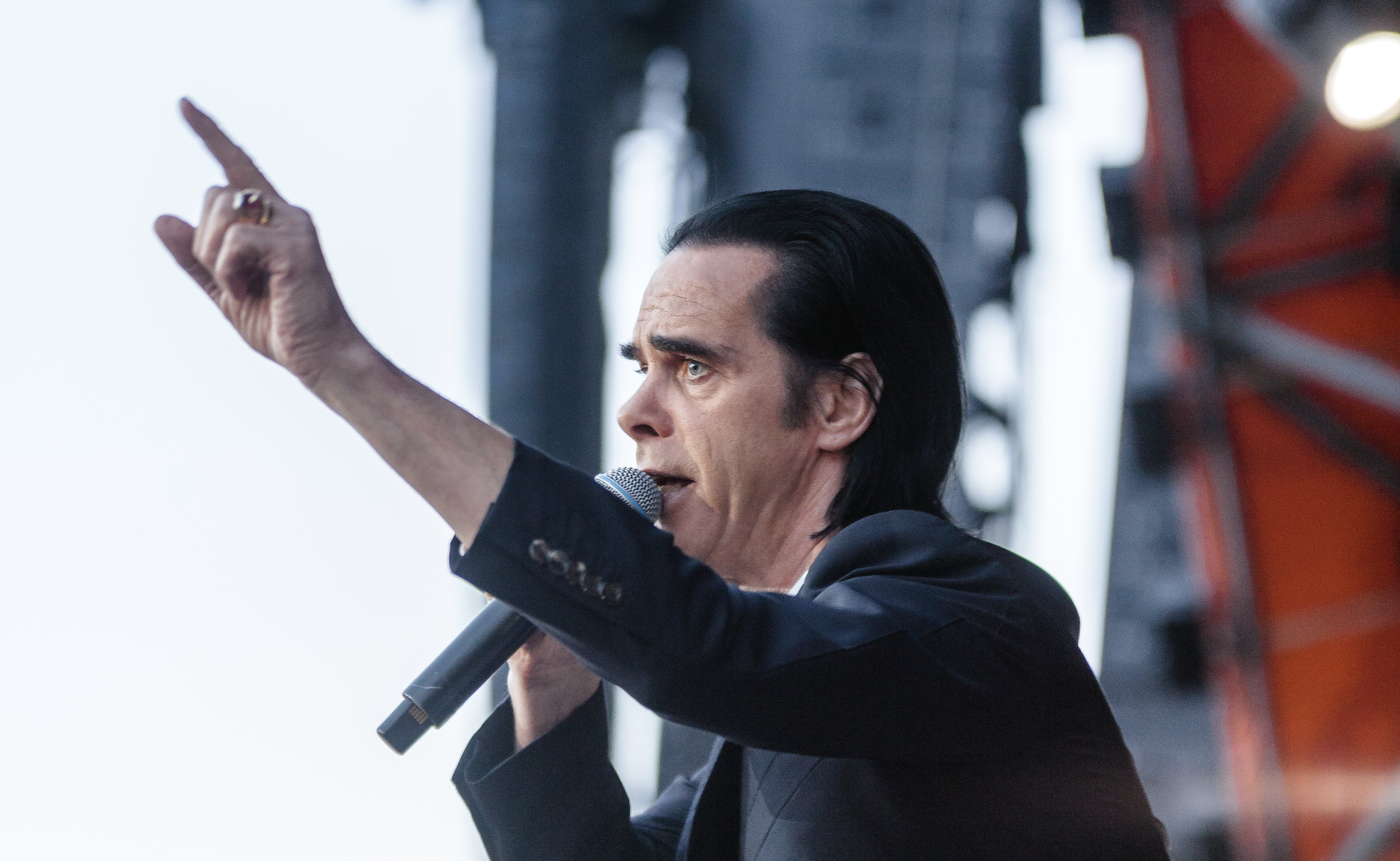

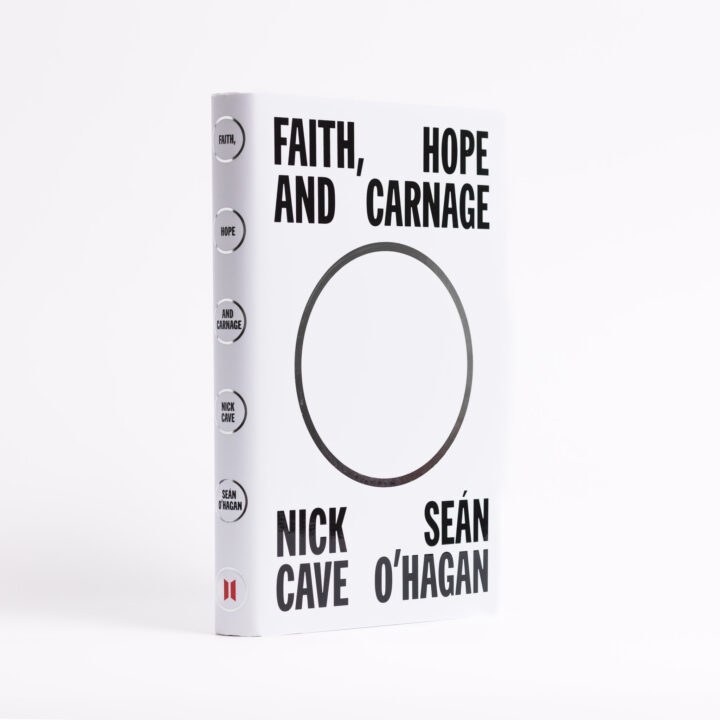

Over Christmas, I finally made time to read Faith, Hope, and Carnage, a book of recent interviews between music journalist Sean O’Hagan and one of my musical heroes, Nick Cave. A prolific songwriter, Cave has long been the front man of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds and was previously the lead singer of the Birthday Party in the 1970s and early 1980s. In recent years, he has done some of the most prodigious work of his career with fellow Australian Warren Ellis. He has composed numerous film scores, written volumes of poetry, appeared in films, and recently sculpted a series of ceramic figurines about the life of Satan.

Cave’s style is one-of-a-kind: avant-garde, manly, and most of all, deeply religious—and the book shows us all of it. Full of heartfelt—sometimes heart-wrenching—sincerity, Faith, Hope, and Carnage is a must-read for fans but an equally valuable resource for anyone interested in the intersection of modern art and Christianity.

For my part, Cave’s music has been a trusted companion in both good times and bad. Although I was a casual fan in the 1990s, my first major exposure to him came in 2004 when my then-girlfriend (now wife of over seventeen years) gave me the double album Abattoir Blues / The Lyre of Orpheus. To this day, I often put on the song “Breathless” for a blast of joy—the feeling of being in love despite whatever mess there may be in the world around me:

Still your hands

And still your heart

For still your face comes shining through

And all the morning glows anew

Still your soul

Still your mind

Still, the fire of love is true

And I am breathless without you

More recently, during the Covid lockdown of early 2020, I took up long-distance running, and on my excursions in the fresh air, I would listen again and again to Cave’s devastating 2019 record Ghosteen, which he wrote as a meditation on grief after the tragic death of his fifteen-year-old son Arthur, who fell to his death from a cliff near the family’s home in East Sussex, England, in July 2015. It is undoubtedly the work of a deep Christian believer but not the happy-clappy variety, thank God. I couldn’t take blithe optimism during those strange days. On “Sun Forest” he sings,

And a man called Jesus, he promised he would leave us with a word that would light up the night, oh the night, but the stars hang from threads and blink off one by one and it isn’t any fun no it isn’t any fun to be standing here alone with nowhere to be with a man mad with grief and on each side a thief and everybody hanging from a tree, from a tree, and everybody hanging from a tree.

Cave’s back catalog has served as a crutch and a springboard for me in different ways and at different times, and especially during recent, recurring periods of high-functioning anxiety and depression (or writer’s melancholy, or whatever it may be). On “Brompton Oratory” from his 1997 album The Boatman’s Call, for example, he processes a painful break-up from fellow musician Polly Jean Harvey by sitting in a beautiful church—an outpost of the kingdom of heaven, a house of healing in the middle of the busy city of London. He sings:

And I wish that I was made of stone

So that I would not have to see

A beauty impossible to define

A beauty impossible to believeA beauty impossible to endure

The blood imparted in little sips

The smell of you still on my hands

As I bring the cup up to my lips

By contrast, when I’m feeling less vulnerable and in the mood for a rousing jolt from a deity who suffers no fools and allows for no rivals, I crank up “Red Right Hand,” which readers may recognize as the theme song to the Netflix mob drama Peaky Blinders.

Although his songs have been saturated with biblical themes and imagery from the beginning of his career, Cave has long been cagey about his specific doctrinal commitments. But in the wake of Arthur’s death, the pain of unimaginable loss clarified many things. Some of the anguish he and his wife, Susie Bick, were experiencing is documented in Andrew Dominik’s 2016 documentary One More Time with Feeling, and on Cave’s subsequent recordings—of which there have been a great many. The book is downright apocalyptic, in the literal sense—a total unveiling that finally points to hope.

About his Christian identity, he says, “The word ‘spirituality’ is a little amorphous for my taste. It can mean almost anything, whereas the word ‘religious’ is just more specific, perhaps even conservative, has a little more to do with tradition.” He elaborates, “Religion is spirituality with rigour, I guess, and yes, it makes demands on us.” He talks about reading the Bible and Flannery O’Connor and Marilynne Robinson, about going to church, and about the choice of faith. “I believe,” he succinctly concludes.

He says about his prayer life, “Prayer is a kind of concentrated listening. For me, prayer creates a silent, contemplative space where the soul has its place to speak. And, for me, prayer is not so much talking to God, but rather listening for the whispers of His presence.”

“I believe,” he succinctly concludes.

Cave also talks at length about a sort of ministry he has called The Red Hand Files. Every day, fifty to a hundred people write him emails asking questions, sometimes about his art and life, but mostly seeking advice about their own struggles. He reads every letter and answers many of them publicly: “Each answer says ‘I matter. You matter. We are of consequence.” Describing his replies almost as an internet version of a corporal work of mercy, he says, “The work is a form of salvation.”

About suffering, he says, “Suffering is, by its nature, the primary mechanism of change. . . . God bestows upon us these terrible, devastating opportunities that bring amelioration and transformation.”

About mourning, he says, “There can be a kind of morbid worshipping of an absence. A reluctance to move beyond the trauma, because the trauma is where the one you lost resides, and therefore the place where meaning exists.”

About grief, he says, “Grief gave me a reckless energy. It afforded me a feeling of invincibility and a total disregard for the outcome, a sort of fearless abandonment to destiny. The worst had happened.”

He reflects on the pandemic, which he calls “the calamity of our time.” He talks about his past drug addiction, his childhood in Australia, social media, and modern cancel culture. He calls wokeism “akin to a fundamentalist religious impulse.” He talks about masculinity, marriage, and fatherhood, and he tells a lot of behind-the-scenes tales about the creation of some of his most celebrated songs and albums. He even describes the four pieces of religious art that have shaped his artistic vision: Grünewald’s Crucifixion, Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà, Rodin’s Christ and the Magdalen statue, and the huge painting The Beheading of John the Baptist by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. He expresses his admiration for St. John of the Cross, Saint Teresa of Avila, William Blake, and St. Augustine.

He comes back frequently to his son Arthur, the person he loved and loves still—the person whose loss will define his life until the end. O’Hagan asks, “Is Arthur a kind of guardian angel?” to which Cave replies from the heart, but with theological acumen, “Well, he does protect me, but he is not a guardian angel. Arthur is my son and he died. He exists just beyond my vision and my reason and a whole sea of tears—as a promise, maybe, or a wish.”

Finally, it’s about the art: “Music is a spiritual currency unlike any other in its ability to transport people out of their suffering.”

Thank God for Nick Cave, and check out Faith, Hope, and Carnage for one great musician’s perspective on the things that matter.