This piece first appeared in the Spring 2020 “The Four Last Things” issue of Evangelization & Culture, the quarterly journal of the Word on Fire Institute. You can learn more and become an Institute member today to read more pieces like this.

To be sure, William Shakespeare’s Hamlet is one of the most complex, mercurial figures in all of literature. Haunted (literally) by the ghost of his murdered king-father, Hamlet spends the majority of the play ruminating and vacillating over what he is now to do. His queen-mother seems little concerned with mourning her recently dead husband, and within a month of King Hamlet’s death, young Hamlet’s uncle Claudius (brother to the deceased king) has usurped not only his brother’s crown but also his marriage bed. In his grief and confusion, what is young Hamlet to do?

Hamlet’s mother tries to counsel him: “Good Hamlet, cast thy nighted color off, / And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark.” His uncle reprimands him, “To persever / In obstinate condolement is a course / Of impious stubbornness, ’tis unmanly grief; / It shows a will most incorrect to heaven.” His friend Horatio tempers him, “These are but wild and whirling words, my lord.” And his love Ophelia prays for him: “O, help him, you sweet heavens!” But their words are to no avail.

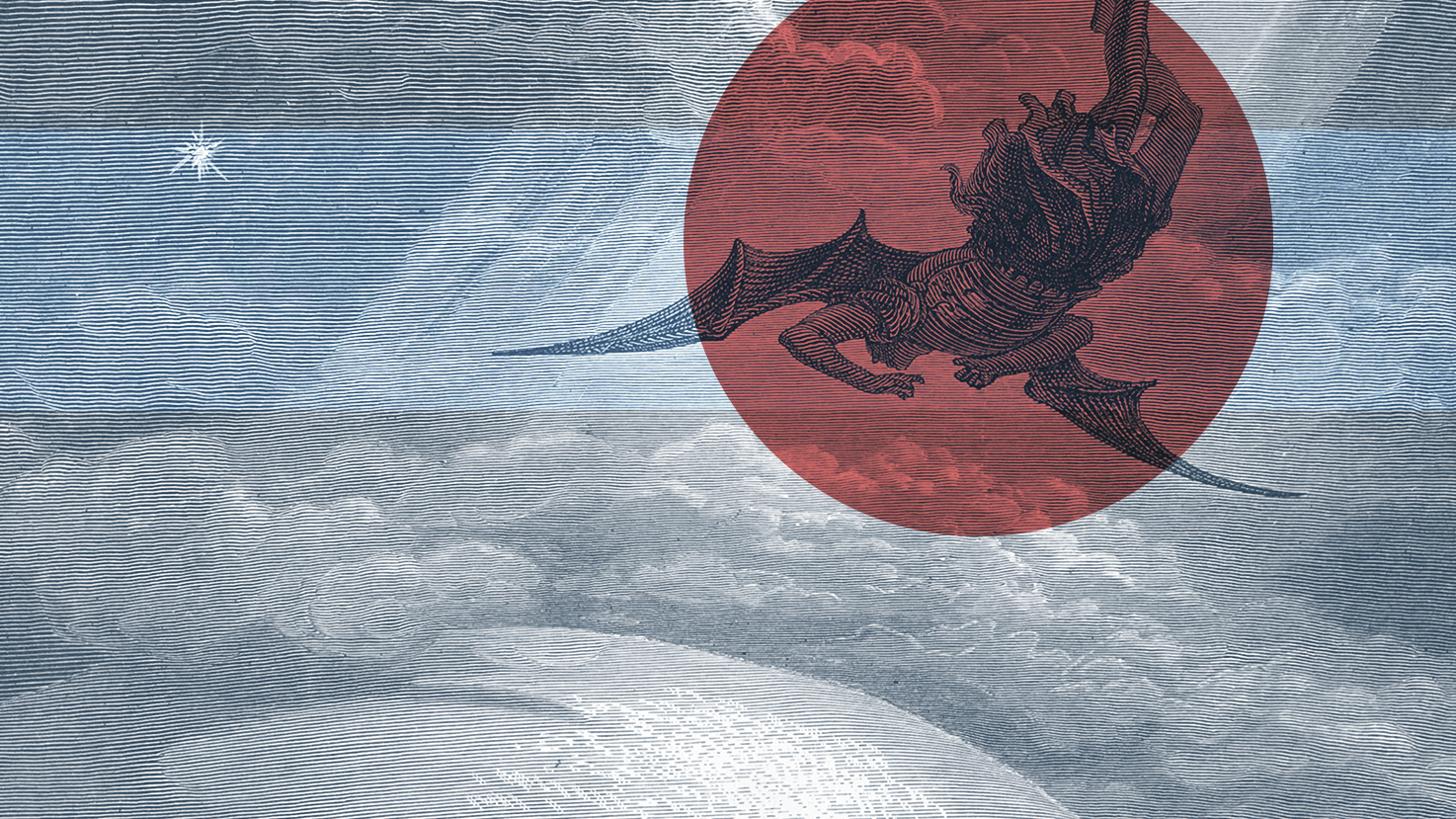

Instead, it is the silent voice whispered through gritted teeth and the blackened gaze staring from empty sockets that pierce Hamlet’s soul. In an image that is emblematic of William Shakespeare, Hamlet holds the recently disinterred skull of his childhood jester and erstwhile father figure, Yorick, in his hand. And in his grief, the young man loses himself.

Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio: a fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy: he hath borne me on his back a thousand times. And now how abhorred in my imagination it is! My gorge rises at it. Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft. Where be your gibes now, your gambols, your songs, your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one now to mock your own grinning—quite chap-fall’n?

Knowing the richness of Yorick’s laughter and the warmth of his company, Hamlet confronts the ephemerality of life and the barrenness of death. It is death embodied in a skull—a moment of memento mori—that awakens Hamlet from his paralysis. And now, he is finally moved to act. Death has a way of silencing, shocking, and moving us. Faced with our own mortality and that of those we love, we begin to see things in sharper focus. What limited us before is no longer insurmountable (or, in some cases, even relevant). What distracted us previously is easily shifted from view. For a moment, the world is seen anew. This is what matters, we discover, and it matters now. Hamlet’s moment peering into the skull of Yorick carries echoes of Christ’s death and sacrifice for us. A man infinite and excellent who had borne us on his back a thousand times hangs impaled and dead on a cross. It shocks us. It opens our eyes. It takes our breath away. And it moves us to act. Death has a way of doing that.

Or it should.