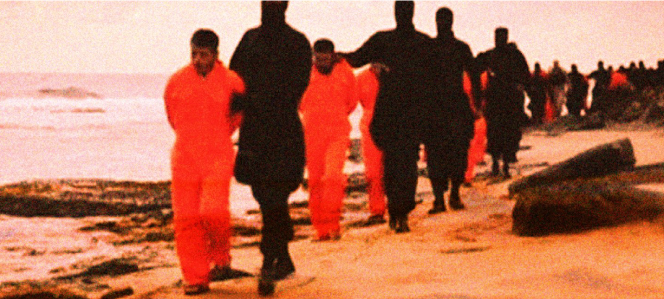

This February marks the four year anniversary of the martyrdoms of 21 migrant workers in Libya, put to death by ISIS for their Christian faith. All but one of the men were Coptic Christians, and the last man, Matthew, was a Ghanaian man whom the ISIS kidnappers had not initially targeted, but who would not renounce his faith or part from his brothers in Christ.

Martin Mosebach tells the stories of each of these men, as far as he can, in his new book The 21: A Journey into the Land of the Coptic Martyrs (ably translated from German by Alta L. Price). Until their deaths, they were anonymous in the eyes of the world. They left minimal written trails (only some were literate).

So, to tell their story, Mosebach shares as much of their individuality as he can, but he also presents a portrait of their world. To know who these men were, he invites us to know who they belonged to and what traditions shaped their lives, formed their wills, and inflamed their love of God.

Mosebach narrates his visits with the families of the martyred men. Their sons, brothers, and husbands left home in order to provide for their families’ material needs, sending money home from their work in Libya. After their deaths, many of the families have stories to tell Mosebach about how their loved ones are still taking care of them, crediting them with healings and visions.

In the homes of the martyrs, Mosebach saw that every family had a little oratory set up. Some of them displayed images of the martyred men that drew on older traditions of Orthodox icons; others photoshopped images of the men from their national IDs to set crowns upon their heads and dress them in priestly vestments.

When Mosebach looked closely at the relics displayed in these cabinets, he saw a similar blend of the traditional and the quotidian.

The bishop of a neighboring diocese had taken the Pauline notion of Christian life as a race or a competition quite literally and given the families polished metal trophies, as if the martyrs were a victorious soccer team:

The cabinets usually stand in their own small room, an oratory, which houses not only the reliquaries and trophies but everything else the men left behind: shirts and shorts; jellabiyas and mobile phones; their liturgical robes; the embroidered white tunics they wore in the church chorus; the cymbals they played during the liturgy; souvenirs of their many pilgrimages; and even the Bibles of those who could read.

The image of the cell phones next to the Bibles and the tunics struck me at first as jarring. Like the (somewhat kitschy) photoshopped images, the idea of treating a phone as a second order relic seemed too modern for martyrdom.

But, as Mosebach’s book drives home, martyrdom is not a matter of antiquity. The Copts Mosebach visits have endured over a thousand years of persecution. William Dalrymple’s From the Holy Mountain: A Journey Among the Christians of the Middle East is a thorough and moving tour through the travails of Christians throughout the modern Middle East. And, in our own Church, we need look back no farther than 2016 to find the witness of Fr. Jacques Hamel, martyred while offering Mass in the Normandy region of France.

Those who die in odium fidei are the saints we find it easiest to recognize, because their love of God is thrown into sharp relief by the torments they suffered. Other saints, who poured themselves out in patient, persistent love, may take longer to recognize. St. Therese of Lisieux and Bl. Pier Giorgio Frassati are saints of this type, and there are many more whose names we do not know and whose deeds will go unremarked until, if we are so blessed, we encounter them in heaven.

As I pass through my everyday life, untroubled by the dangers the Coptic martyrs faced, I may handle the possessions of a friend who is allowing Christ to grow in him. I may help wash the dishes that will one day be second-order relics, might borrow a handkerchief that could one day be cut up for holy cards. The deaths of the Coptic martyrs were extraordinary, but their sainthood is what every person I meet was made for.

In his sermon “The Weight of Glory,” C.S. Lewis reminds us that the transformation of the 21 is what is asked of all of us:

There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.

We are all called to be saints, whether or not our faith is put to the violent and visible test that the 21 endured. We are all made to leave the kind of traces they left behind—relics, miracles, marturion—a witness of our own.