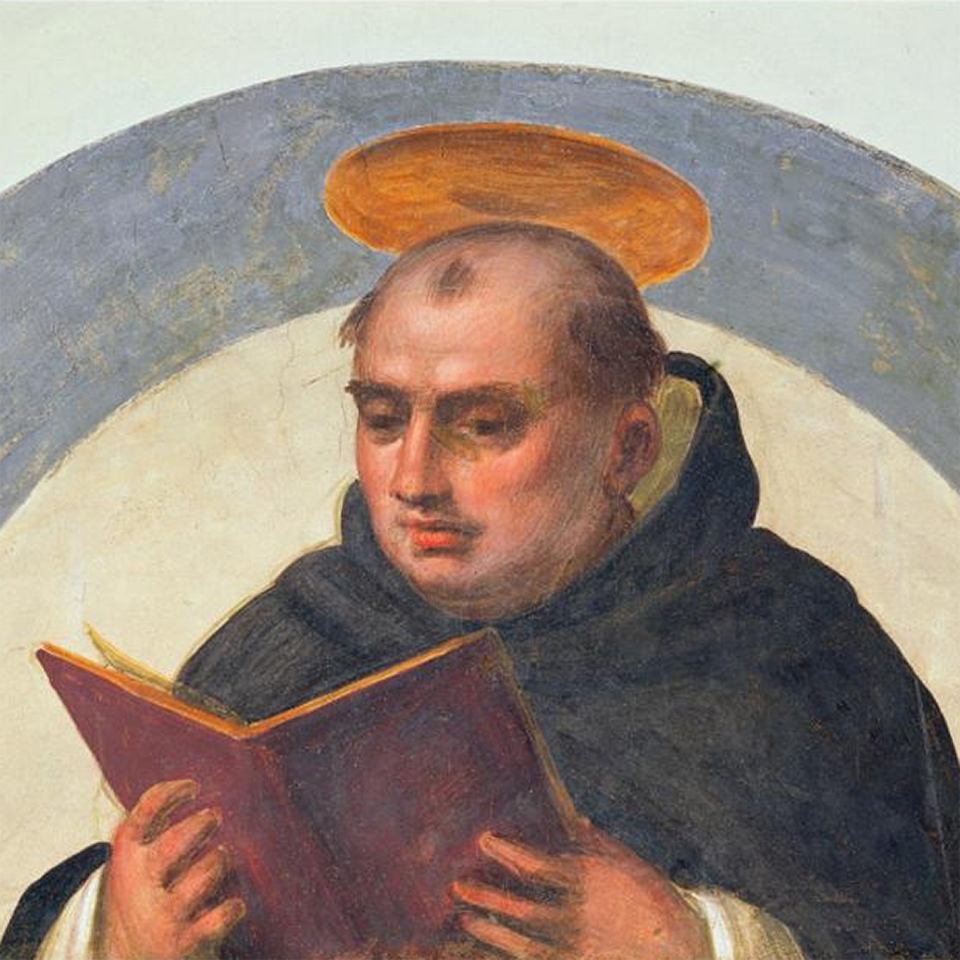

In his 1998 encyclical Fides et Ratio, St. John Paul II affirmed the importance of the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas for the Church’s dialogue with the modern world. In the history of the Church, the influence of Aquinas has ebbed and flowed. After the Reformation, the Church drew from the teaching of Thomas to refute misunderstandings that had arisen about the nature of grace and the importance of the sacraments. Inspired by Thomas’ social and political thought, Pope Leo XIII, in the late nineteenth century, wrote his encyclical Aeterni Patris. This was a landmark document calling for Catholic engagement with modernity. It was the genesis of what would become a major part of the Church’s evangelical message to this day—her social teaching. Here I argue that the thought of St. Thomas is again required by the Church to dialogue confidently with modern science, and offer three reasons why.

The Truth of Things

First, Thomas invites us to love both the natural sciences and the science of faith. Under the influence of St. Albert the Great (c. 1200-1280), Thomas appreciated the scientific study of creation as an enterprise of observation, discovery, and contemplation of all that God had made. He saw a harmony between science and faith, since, for Thomas, it is truth that unites both faith and the natural sciences. He wrote that “all truth irrespective of who expresses it, comes from the Holy Spirit” (Summa theologiae, 1-2.109.1). This means that for both the believer and the scientist, what unites them is a passion for what is true.

What also unites them is a disdain for relativism. The implications of this insight for us today is that we should not be afraid to dialogue with science—to know its power and its limits. When I worked in science, the study of physics, chemistry, and biology were not threats to my faith but routes to contemplation of all God’s handiwork, which moved me to praise him even more.

The First Cause

Second, Thomas helps us refute the conclusion of atheistic scientists like Richard Dawkins who say that there is no God since he cannot be found within the material world—which, according to atheists, is the only reality there is. In Dawkins’ own words: “Gaps shrink as science advances and God is threatened with eventually having nothing to do and nowhere to hide” (The God Delusion). To use an analogy, this approach would be like dissecting a play, finding out about all the characters and, not finding the author of the play in that search, concluding that an author must not exist. Scientific tools of observation, on their own, cannot account for all that is. Neither are we mere external observers of the play that is unfolding around us. We are participants in an ongoing drama where God not only creates the actors but gives them free will and sustains them in existence.

In the words of St. Thomas, God is the primary cause of all that exists, and his creation is full of secondary causes that are at work every day—one example being the law of gravity that keeps us from floating out into space. God as first cause and gravity as a secondary cause do not compete with each other. Rather, God as first cause grounds the law of gravity, for he designed it for the order and stability of the universe. Contrary to the claims of scientism, the autonomy of nature is not proof of a reduction of God’s power, much less evidence he doesn’t exist. Rather, it is a sign of his goodness. In the words of the International Theological Commission: “God’s action does not displace or supplant the activity of creaturely causes but enables them to act according to their natures and, nonetheless, to bring about the ends He intends” (Communion and Stewardship, 2004, no. 68).

And so, the next time someone tries to debunk your faith in God’s existence by pointing to the natural world and telling you that God is not found there, we might employ the wisdom of Thomas and point to his distinction between first and secondary causes. As first cause, God creates and sustains all things but transcends them.

The Knowing

Third, Thomas helps us understand the amazing intelligibility of the universe that most of us take for granted, especially atheist scientists. Why does the math of our minds resonate with the math of the universe expressed in the laws of physics? This question was not lost on scientists like Albert Einstein, who once remarked: “The most incomprehensible thing about the world to me is the fact that it is comprehensible.” Again, St. Thomas comes to our help here. All things were made by God through the same principle of order (see Prov. 8:22ff.). For Christians, this principle of order is the “Word of God” described in the prologue of St. John’s Gospel and identified by St. Paul as Jesus Christ the Son of God, through whom “all things were made, things visible and invisible” (Col. 1:16). Therefore, there is a correspondence between human beings and the rest of creation. Not only that, but because God made human beings in his own image and likeness, our capacity to reason participates in God’s own power of reason that is faithful to what is true and right. Thomas helps us to understand not only the relationship between our minds and the things we understand but also how our knowing and understanding is only possible by the light of his grace. Again, this insight ought to make science more humble as it recognizes the limits of its own empirical tools. The genius of Thomas reminds us that science can only be done within the relational matrix of the universe that we are part of. Therefore, science has moral boundaries that must be respected. As science advances, the wisdom of Thomas tells us that natural science is not the only source of knowing and understanding. For as he once remarked: “The one who has charity has right judgment both of what can be known . . . and of what can be done” (Upon Reading the Letter to the Philippians, 1.2). The one who loves, knows.

The challenge presented by scientism to the Church today is daunting. With the insights of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church can be inspired to meet that challenge in the three ways outlined above—to love the natural sciences and the truths they discover, for scientific truth and religious truth always come from the same source. Thomas also gives us the tools to respond to the confusion of the relationship between first and secondary causes. Lastly, Thomas tightly connects the scientist, observer, and believer in our common task to interpret what we see and find in our wonderful universe.

On his feast day, we give thanks to God the Creator of all for the wisdom and teaching of the Angelic Doctor, who equips us with the language and a new confidence to dialogue in a scientific age.