This piece is an excerpt adapted from Holly Ordway’s Tolkien’s Modern Reading: Middle-earth Beyond the Middle Ages, Chapter 6.

In one of the rare instances when Tolkien said what The Lord of the Rings was “about,” he explained that “it is about Death and the desire for deathlessness.” Tolkien’s approach to this topic provides the fitting groundwork for reflection on this anniversary of his death on September 2, 1973.

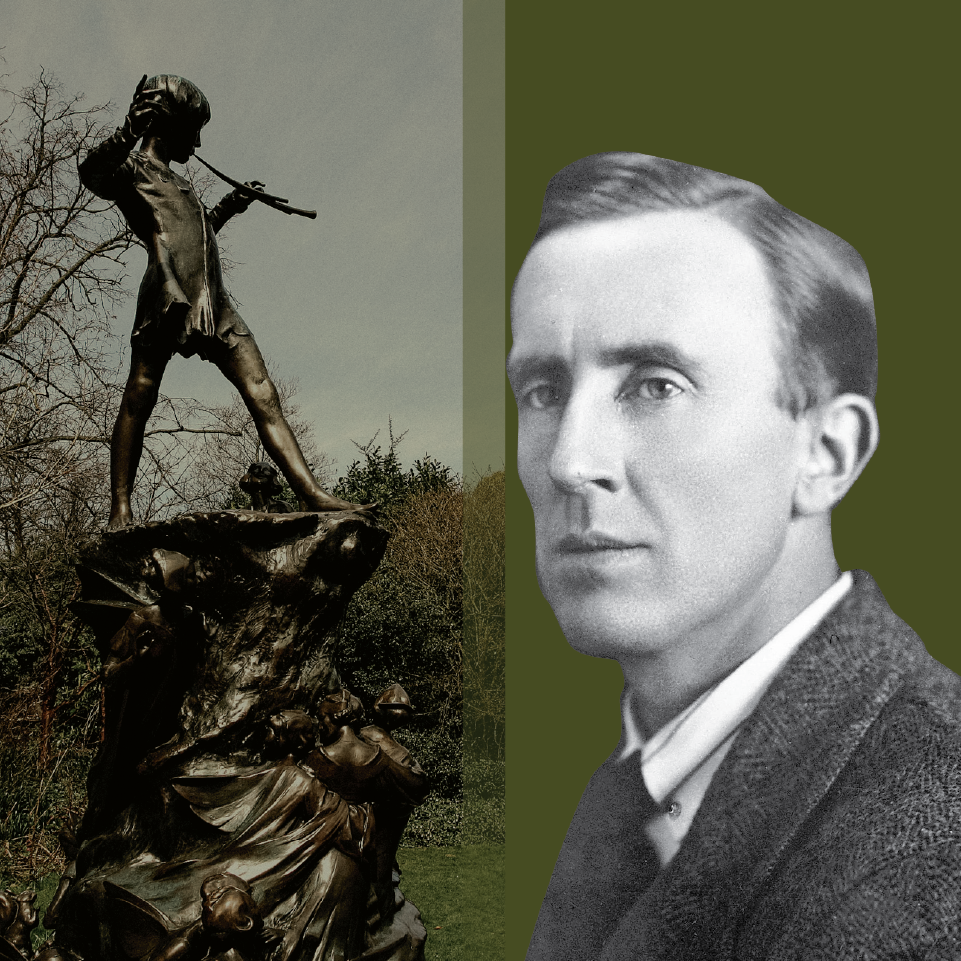

We can gain some insight into Tolkien’s views by means of another literary creation: the deathless boy called Peter Pan, the creation of J.M. Barrie. Although we might now be more familiar with the Disney version, Peter first appeared in the 1902 novel The Little White Bird, followed by a stage play in 1904, and then subsequently by two further novels. Barrie also wrote a number of other plays, including Dear Brutus and Mary Rose, in which he explores the intersection (often dangerous and traumatic) between human and fairy worlds.

Tolkien knew Barrie’s work and had seen Mary Rose and Peter Pan performed. He remarks in his essay “On Fairy-stories” that Barrie was successful in making his stories believable, but he did so with “characteristic shirking of his own dark issues.” And this shirking he found too in Barrie’s development—or rather non-development—of the character of Peter Pan himself. Tolkien commented that “children are meant to grow up and to die, not become Peter Pans.” In a draft of the essay, he adds that this would be “a dreadful fate.”

Arrested development is a common enough response to trauma, of course. It can also be adopted as a sort of avoidance behavior, and as such, it has been described as a kind of religious, even idolatrous belief: what C.S. Lewis called “Peter Pantheism,” faith in the (false) power of eternal youth. The problem is not the continued enjoyment of things that children enjoy, such as fantasy stories, but rather the refusal to grow up and accept the responsibilities of adulthood. As Lewis explains, “arrested development consists not in refusing to lose old things but in failing to add new things.”

It is an understandable mistake, but a mistake nonetheless, and Tolkien knew as much. It was the theme of death, not the avoidance thereof, that he himself would treat with so much care in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien himself had plenty of “dark issues” to face, including the death of both his parents by the time he was twelve years old and his military service as a Signals Officer in the Great War. The origin of the Silmarillion can be found, according to John Garth, in the writing of “The Fall of Gondolin” during Tolkien’s stay in hospital in late 1916 straight after the Battle of the Somme; it is a tale whose storyline and imagery show it to be “clearly a product of Tolkien’s war experience.”

A similar tackling of trauma through writing occurred in 1944 after a visit to Birmingham brought reminders of his friends who had died in the trenches of France: “I couldn’t stand much of . . . the ghosts that rose from the pavements,” Tolkien confessed in a letter to his son. Significantly, three weeks later, in a burst of creativity, he wrote the Dead Marshes section of The Lord of the Rings, and having had this “artistic catharsis,” Garth reports his writer’s block was broken and he was able to carry on rapidly with the tale. By facing rather than avoiding the darkest experiences of his life, Tolkien was able to transmute the remembered horrors of the Great War into some of the most powerful and haunting scenes in The Lord of the Rings.

But both of these cathartic moments were in the future when Tolkien first encountered Barrie. Tolkien saw the play Peter Pan in 1910, and recorded in his diary, “Indescribable but shall never forget it as long as I live.”

Between 1915 and 1917, Tolkien developed an idea that appeared first in the poem “You & Me & the Cottage of Lost Play” and then in The Book of Lost Tales as “The Cottage of Lost Play.” Here, we find a traveler coming to a strange house filled with happy children. It is an idealized Peter Pan environment transposed into the nascent legendarium; not only do we have the ageless children living happily away from their families, but we also have the detail of these children leaving their Neverland, as it were, to interact with ordinary children in the rest of the world, just as Barrie’s Peter does.

The “Cottage” idea did not endure in Tolkien’s mythology. Christopher Tolkien writes that this idea “was soon to be abandoned in its entirety, and in the developed mythology there would be no place for it.” Nonetheless, Tolkien retained an interest in the Peter Pan story. Early in his life, he drew on its more nostalgic and sentimental aspects, but later, he seems to have attended more fully to the dark element of the story.

The Peter Pan of Barrie’s play and books is not quite the same as the Disney version. Barrie’s story, in any of its forms, is unsettling; death is an underlying theme, as is a simultaneous longing for and rejection of mothers. Peter himself, the boy who never grows old, has a streak of cruelty, and is depicted as somehow outside the normal concerns of human beings.

Tolkien chose ultimately not to include his early Elvish Neverland in the mature legendarium. Though deeply impressed with Peter Pan in his early days, Tolkien wrote “You & Me & the Cottage of Lost Play” before seeing active service on the Somme. Having faced the reality of carnage in the trenches of the Western Front, he had to revise his view of Peter’s cheerful declaration, “To die will be an awfully big adventure.” In the play, Peter makes this statement as if he were a real boy but in a form of play-acting. Eternally young, Peter is able to view death cavalierly precisely because it remains only an idea, not a future reality. We might ask whether Tolkien’s long-lived Elves are representative of a lingering Peter Pantheism in Middle-earth. As Garth points out, “It was Peter’s perpetual youth that came closest to the mark during the Great War, when so many young men would never grow old; and Tolkien’s Elves, forever in the prime of adulthood, hit the bullseye.”

True enough; but even Elves may die, and this is perhaps Tolkien’s point of departure from Barrie’s vision. The Elves’ perpetual life operates within the created order; they are not inherently immortal, as are the angelic Valar. And even in “the circles of the world,” Elves turn out not to be utterly invulnerable: they may choose to live a mortal life, as Arwen does in her love for Aragorn.

Tolkien also explored the dark side of the desire for eternal life in one of the earliest and most significant stories of the Silmarillion: the Fall of Númenor. The Númenóreans, though they have very long lifespans, nevertheless become obsessed with cheating death entirely, even setting out to invade Valinor, the land of the immortals, an act of rebellion that leads to Númenor itself being utterly destroyed. Tolkien explained in a letter that their extended life—itself a gift—is in fact their “undoing” or at least a “temptation”: it “aids their achievements in art and wisdom, but breeds a possessive attitude to these things, and desire awakes for more time for their enjoyment.”

Death is indeed a great adventure; so great that it must be handled not with a boyish heartlessness or cheerful indifference, but in another way—more serious, more equivocal. Tolkien was well situated to tackle these themes and to do so in a mature and considered fashion, fully aware that unnatural long life, such as the Ring brings to Gollum, is a “dreadful fate,” not unlike Peter’s inability or refusal to grow up. Here, we see how Tolkien—working within the genre of fantasy and responding to other writers’ engagement with the theme—is able to explore one of the most profound issues of human life: the experience of Death, and the desire for deathlessness.