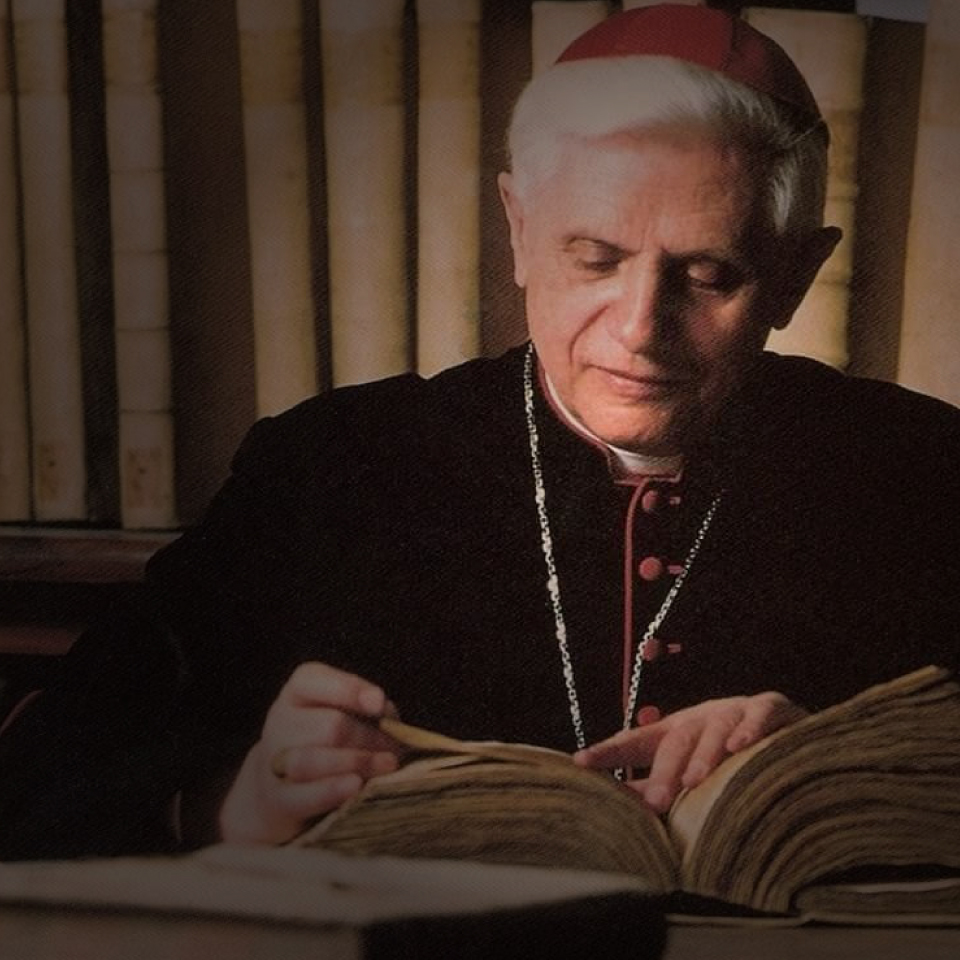

The Pope Emeritus, whether as Benedict XVI or Joseph Ratzinger, ranks among those I call my first and best teachers within Catholicism. And because I am a needy and often recalcitrant student, I need a lot of them, so he is joined by St. Philip Neri, Francis de Sales, Thomas Merton, and the Psalmist among many other fine instructors. “Professorial” is a word frequently used to describe Ratzinger’s writing, but I’ve always thought “avuncular” might be a better descriptor. I may approach the writings of the others with the appreciation of a student attending a favorite class, but whenever I pick up a book or encyclical or speech by Joseph Alois Ratzinger, I feel like I’ve come into a room and found a favorite old uncle who greets me with affection and bids me to have a little tea while he shares the fruits of his quiet contemplation.

Yes, that sounds fanciful, but his writing is so accessible and clear, even his more complicated ideas are rendered with such a sense of thoughtful warmth and a care for language, that each encounter leaves me feeling the same way: like I have been engaged, not lectured to, and lovingly so. He is the clearest of theologians, neither pedantic, nor impenetrable, possessing a rare and paradoxical gift: in very simply expressed thoughts, he forces me to consider things both profound and complex.

There are a few Ratzingerian nuggets I keep returning to when I find my self-assigned lectio to be lacking. In each case, they pull me into the sort of prayerful contemplation that leaves me refreshed, informed, and eager to read more, think more, pray more, that I may better know Christ and love Christ, and my self too: “God’s love for his people is so great that it turns God against himself, his love against his justice” (Deus Caritas Est, 10).

We see the proof of it over and over again in Scripture. The Jews, who are not quite getting it that they are ruled by the King of Creation, demand a flesh-and-blood king to judge them, like the other nations. Perhaps they believe a human king will better understand them, or that a human king can be worked upon in ways they can undertake—ways beyond the mysteries of faith, prayer, and surrender. And God responds not by calling down wrath upon them for their cagey short-sightedness but by giving them what they ask for and more: a temporal king in David, and eventually the King of kings, Jesus of Nazareth, for eternity—with us, flesh and blood, soul and divinity, through all time.

We see it in the New Testament—most profoundly in Christ’s Passion, which is the definitive act of divine love chosen over justice. But we rarely put it together that way. We rarely stop to think that while we are telling God what it is we want or need, he does not simply take insult and reply, “My love is not enough for you?” He responds to our stated needs and desires in specific ways.

It’s astonishing if you think about it. Because of his great love, God turns against himself—negates, or reconfigures, or delays his own desire—in order to serve created creatures, who so seldom understand. If we really internalized this, we would cling to Jesus’ promise in the Gospel of John: “Whatever you ask me, in my name, I will do it.” We would deeply ponder and key into the clue Saint James drops in his epistle: “You ask and do not receive, because you ask wrongly, to spend it on your passions.”

All that from a brief encounter with a single line from God Is Love.

Here is another quote, from the same source, and it is one that bowls me over each time I read it, because Benedict’s language here is so unexpectedly, nakedly vulnerable yet free: “Seeing with the eyes of Christ, I can give to others much more than their outward necessities; I can give them the look of love which they crave” (18).

Goosebumps, every time. Because it is so spot-on, such a irrefutable recognition of what lies at the very core of each of us: the be-longing for that deep, penetrating beam of love, which we crave but often cannot bring ourselves to receive, because it is a look of utter and complete knowing, as intimate as lovemaking, but with the lights on, so we can deny nothing of what we give, or what we take. Making eye contact is difficult enough for many of us; encountering a look of love—which has nothing to do with lust and everything to do with unconditional, cherishing acceptance—can sometimes feel like more than we can endure. It involves surrendering to being entirely known, which is always a vulnerable thing.

So, too, is consenting to learn to see this way, with the eyes of Christ. This requires an even greater sort of willing surrender, because it means consenting to wade out into a sea full of human fear and rejection, bravely and without any guarantee that anyone will permit themselves to be seen, or to look back. It is, then, a consent to the possibility of living a life wholly misunderstood, destined for a kind of contented loneliness—one to be shared with the very God who is constantly reaching out and finding so much fear, so much anger, so much rejection and distrust, so few reaching back.

Both of these ideas challenge me, because I want to be these things. I want to be the one who understands that God is already offering me in his Trinitarian self a benevolent King greater than any I could encounter in humanity—one intent on teaching me that love serves, and that the greatest king is also a servant; that if I learn to be a servant I will share in that kingship so that, in this way, we shall be one, as joined as lovers, forever. I want to have the courage to learn how to see with Christ’s eyes—to consent to be the look of love to others, despite their fearful reactions, their instincts to look down and turn away.

But I am myself fearful and slow to trust, even though I know that in giving over to these things, I risk nothing—something the Pope Emeritus himself reminded us at the very start of his pontificate, in perhaps his best lesson:

Are we not perhaps all afraid in some way? If we let Christ enter fully into our lives, if we open ourselves totally to him, are we not afraid that He might take something away from us? Are we not perhaps afraid to give up something significant, something unique, something that makes life so beautiful? Do we not then risk ending up diminished and deprived of our freedom? . . . No! If we let Christ into our lives, we lose nothing, nothing, absolutely nothing of what makes life free, beautiful and great. No! Only in this friendship are the doors of life opened wide. Only in this friendship is the great potential of human existence truly revealed. Only in this friendship do we experience beauty and liberation. And so, today, with great strength and great conviction, on the basis of long personal experience of life, I say to you, dear young people: Do not be afraid of Christ! He takes nothing away, and he gives you everything. When we give ourselves to him, we receive a hundredfold in return. Yes, open, open wide the doors to Christ—and you will find true life. Amen.