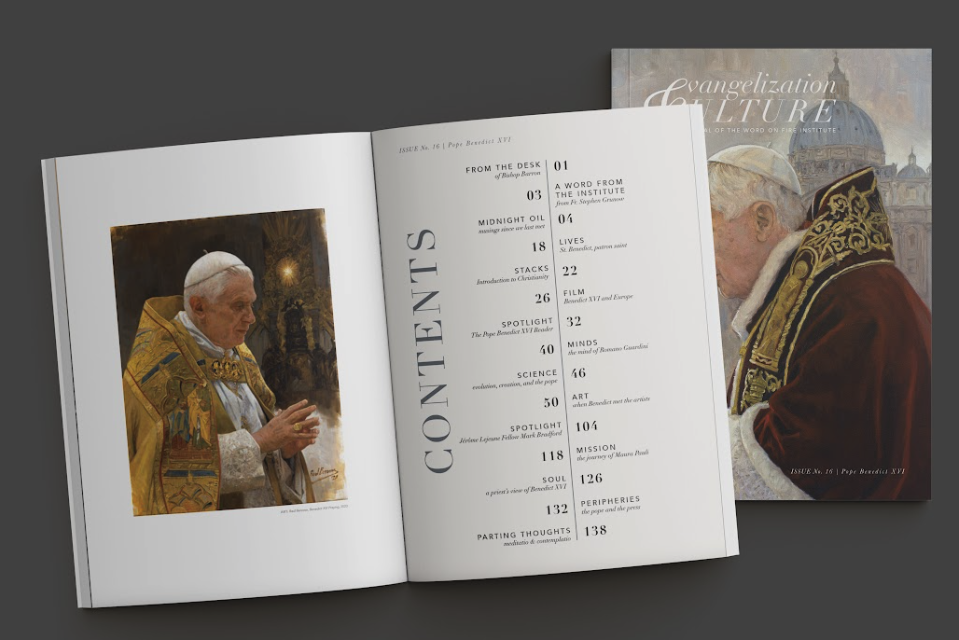

This piece highlights the “Stacks” column featured in Issue XVI “Pope Benedict XVI” of the Word on Fire Institute’s quarterly print journal, Evangelization & Culture.

Introduction and Scope of the Work

While it would be rash to identify a single text of Joseph Ratzinger as his most significant, one would be hard-pressed to find a better candidate for this title than his 1968 classic Introduction to Christianity. A young Fr. Ratzinger wrote this book to counter the “oppressive power of unbelief” that he saw beginning to overtake Western society. The text would become a worldwide bestseller, and its achievement remains as timely as ever as Ratzinger showcases the “real content and meaning of the Christian faith” in an age where Christianity finds itself “enveloped in a greater fog of uncertainty than at almost any earlier period in history.”

That Introduction to Christianity became a massive success had much to do with how it came to be written. This was not merely the product of a towering intellectual working at his desk but the fruit of Professor Ratzinger’s interactions with students across all disciplines at the University of Tübingen. Ratzinger’s down-to-earth style reflects this experience, which enabled him to replicate for his age what Karl Adam had achieved a half-century earlier when endeavoring to capture the Wesen (“essence”) of Catholicism. While adhering to the fullness of the Catholic faith, Ratzinger’s approach in this book is informed by his profound awareness that the trend of atheistic secularism cannot be effectively countered merely by grasping on to “the precious metal of the fixed formulas of days gone by.” To effectively evangelize, knowledge of the Church’s traditional doctrines remains as necessary as ever, yet Ratzinger stressed the vital importance of an aggiornamento—a fresh way of presenting the substance of the Church’s ancient faith. It is with this end in mind that Ratzinger sets out to lead believers deeper into the core tenets of the Christian creed and to demonstrate why they still matter today.

As one might expect of a text that sets out to survey the core content of the Christian faith, Introduction to Christianity covers an expansive range of topics, including the relationship of faith and reason, the historical development of biblical monotheism, Christology, the Paschal Mystery, the Trinity, the resurrected body, and the last things. Most notably, Ratzinger also reflects on what it means to say “Amen” and follow Jesus Christ in the face of the myriad obstacles and doubts that today’s believer inevitably confronts.

The Certitude of Faith and What It Means to Believe in an Age of Unbelief

It is common for Christians to assume that firm belief cannot coexist with the experience of uncertainty and to fear that their harboring of challenging questions betrays a lack of faith. Fortunately for the countless believers whose experience is marked by existential struggle, Joseph Ratzinger stands in an eminent line of great teachers who demonstrate that this is far from the case.

Before tackling this precise issue, Ratzinger begins by addressing a more fundamental question: What does it mean to say “Amen” in the first place? While by no means denying the intellectual component of faith emphasized by Aquinas, this contemporary thinker describes the experience more holistically and phenomenologically in an attempt to capture the heart of Christian existence:

The little word credo [“I believe”] contains . . . a fundamental mode of behavior toward being, toward existence, toward one’s own sector of reality, and toward reality as a whole. . . . It is a human way of taking up a stand in the totality of reality, a way that cannot be reduced to knowledge.

Right from the start, it is evident that Ratzinger does not consider belief primarily an intellectual virtue. Belief means accepting God and his revelation, but it is much more: it means “entrusting oneself to that which has not been made by oneself” and “founding our entire life on him.” As we see here, a major theme of the Introduction is that faith is not faith if we pick and choose which articles of the creed we will accept. Belief means humbly submitting ourselves to Christ and his Church by affirming a meaning that we do not make but can only receive.

Faith’s Truth Is Seen with the Heart, through the “Experiment of Faith”

Another central emphasis of Ratzinger’s Introduction is that the truth of the Christian faith cannot be proven in a scientific laboratory. As pontiff and throughout his career, Benedict XVI stressed that Christianity can be understood only in the laboratory of life by embarking on the experiment of faith. It is of this dynamic that he writes, “Only by entering does one experience; only by cooperating in the experiment does one ask at all; and only he who asks receives an answer.” In another landmark work of dogmatic theology, Ratzinger would echo the thought of his friend Hans Urs von Balthasar by professing that a mystery “can be seen only by one who lives it.” Decades later as pope, Benedict XVI would reiterate that some truths in life are like the windows of a great cathedral: their radiance can only be seen “from the inside” by living the fullness of faith in the heart of the Church.

To drive home this point, Ratzinger draws an analogy from the sciences: “We know today that in a physical experiment the observer himself enters into the experiment and only by doing so can arrive at a physical experience.” Countering the common but misguided notion that we should be able to prove Christianity’s truth to anyone whomsoever, he adds, “There is no such thing as a mere observer. There is no such thing as pure objectivity.” This is by no means to despair of our ability to know the truth of things, but rather a frank acknowledgment that it is futile to pretend that the truth of the faith can be had apart from the endeavor to live it. In saying this, Ratzinger is merely echoing St. Paul’s teaching that man “believes with the heart” (Rom. 10:10) and St. Gregory the Great’s conviction that love is itself a source of knowledge. For Joseph Ratzinger, faith was always about friendship with Christ. He believed that trust was the cornerstone of this bond, and that it required a “leap” to embrace what he and Luigi Giussani independently dubbed the “risky” enterprise of Christian living.

Having said this, it is important to emphasize that Joseph Ratzinger would be the last person to construe what he dubs the Christian’s existential “gamble” as a blind leap in the dark. In concert with the Catholic tradition at large, Joseph Ratzinger spent his entire career working to show how faith and reason mutually reinforce one another. In the Introduction, he explains that the task of reason is “to ensure a responsible reception of the faith—to assist in the process of making what is received more and more our own by handing ourselves over to the truth.” To be sure, then, the believer must do his due diligence in the domain of reason. Yet, at the end of the day, the heart of Christianity is stunningly simple. Joseph Ratzinger’s “introductory” message for would-be disciples of Christ is therefore this: that Christianity is a total way of life, and that to believe is to hand ourselves over to Jesus Christ in imitation of him who handed himself over to death for us.

You’ll find this piece and more in Issue XVI “Pope Benedict XVI” of the Word on Fire Institute’s quarterly print journal, Evangelization & Culture.

The journal is included with membership, along with access to the ever-growing course catalog, WOF Digital all-access pass, community groups, and more. You can learn more and join here.