Just over thirty years ago, on February 25, 1992, R.E.M. collected the Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album, a category only in its second year of existence. Their achievement was the surprise masterpiece, Out of Time, which to this day lives up to its name and deserves its many accolades. The runaway hit from Out of Time, and still R.E.M.’s most famous song by far, is the theologically significant anthem of unrequited love, “Losing My Religion.” For such a quintessentially 90s album, it is both musically and lyrically as fresh and forward today as it ever was.

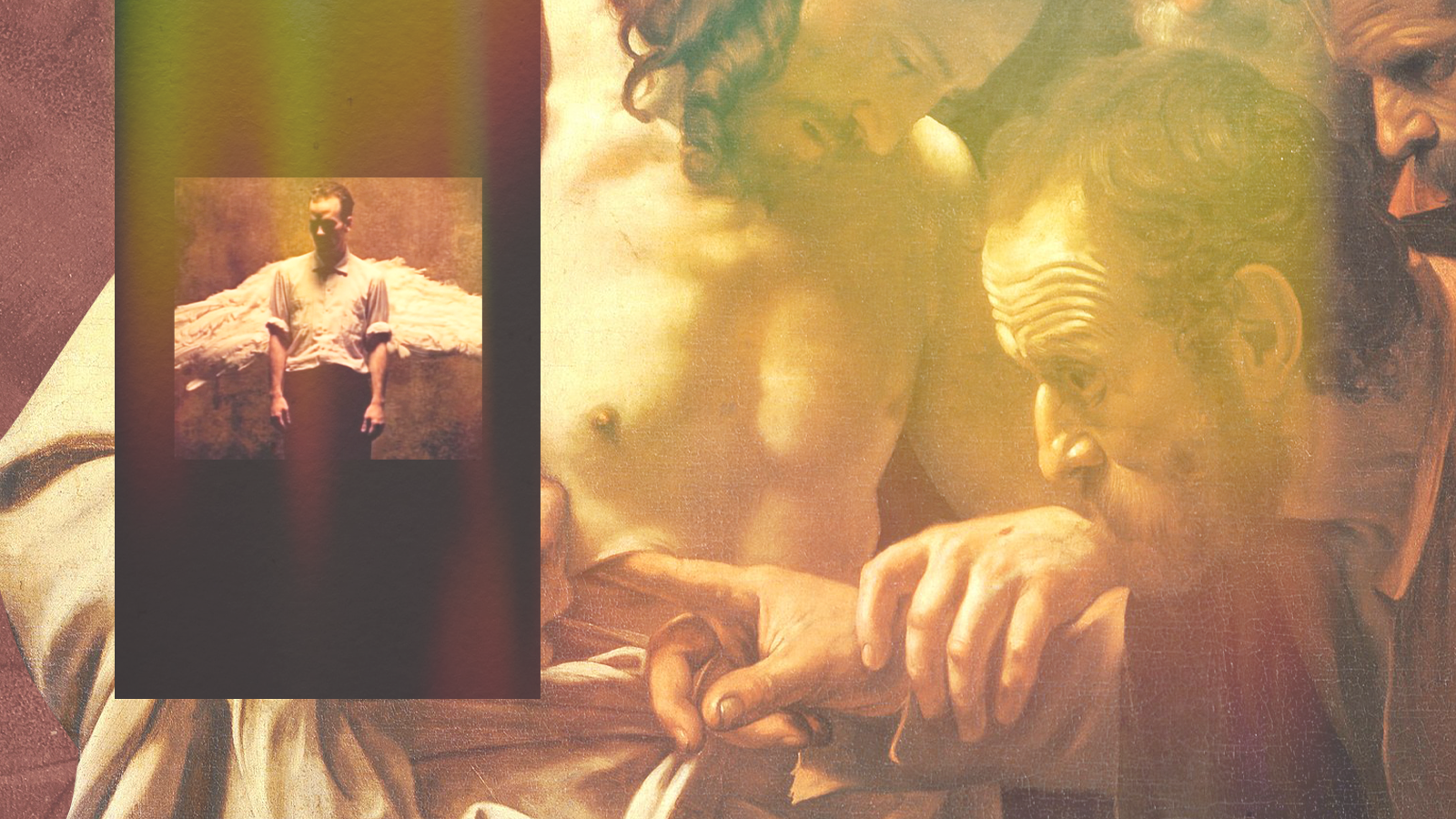

R.E.M. bassist and vocalist Mike Mills has said of “Losing My Religion,” “[It] is a five-minute song with no discernible chorus and the mandolin is the lead instrument. There is absolutely no way to ever predict that that would be a hit.” The video, directed by Tarsem Singh, is an esoteric homage to the painter Caravaggio, the novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez, filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, Bollywood cinema, and the dance styles of David Byrne and Sinead O’Connor. It won big at the 1991 MTV Video Music Awards.

“Oh, life!” We all feel the need sometimes to throw up our hands, look up to heaven, and wonder what it’s all about

The song’s lyricist and singer, R.E.M. front man Michael Stipe, has repeatedly insisted that “Losing My Religion” is not about religion at all but merely takes its title from an old southern expression meaning a feeling of frustration or desperation. But any good love song, and perhaps especially a song about longing, has the potential to grow up in unpredictable ways beyond the life its author intended. In my own struggles of faith and doubt—my own anxiety to be seen and loved by Love himself—R.E.M.’s song has been a constant companion.

As the Church celebrates the Resurrection with Mary, Peter, John, and many of the other Apostles and followers of Jesus, it also lives in the tension of Thomas’ doubt. We are not a mindless collective, programmed in our baptism for ineradicable agreement with the Law of God, but individuals with free will, who, once claimed for Christ, still face countless choices for or against Christ throughout our lives. A particular Christian may, at one point in time, enjoy the blessedness of a robust faith that others envy; but mysteriously, the same person of faith may suddenly find himself standing over the abyss of doubt. Stipe begins “Losing My Religion” with the simplest exclamation of universal uncertainty, with the first syllable drawn out for effect: “Oh, life!” We all feel the need sometimes to throw up our hands, look up to heaven, and wonder what it’s all about.

Stipe then continues in an almost personalist vein: “Oh life . . . is bigger. Bigger than you. And you are not me.” I am me. A broken creature desiring healing from he who is wholly other. I look for him from afar, perceiving rightly or wrongly “the distance in your eyes,” the seemingly insurmountable obstacles lying in the path between total despair and unfathomable fulfillment. In the great gift of my free will, at one moment I doubt my sanity, worth, and purpose, and then the next moment, I find myself inexplicably at peace, in the assurance of belonging to the mystery of reality, the love that set the stars in motion.

In my life of prayer, as well as in my discussions of faith with others, I struggle to find a way between the opposites that Stipe describes. On the one hand, “Oh no, I’ve said too much,” and on the other hand, “I haven’t said enough.” Then, in my spiritual anguish, I fly or fight: “That’s me in the corner,” followed immediately by “that’s me in the spotlight,” and in both cases “losing my religion.” Sometimes, in my shame, I want to avoid being seen by the all-seer at all costs; or else I overcompensate and overperform, acting out of inauthentic zeal. Again, in Stipe’s words, I’m “trying to keep up with you,” absurdly competing for the attention of him who does not compete, and for the love of him who gives it freely.

Or does he? Could it really be true? “I thought that I heard you laughing,” Stipe worries. I can’t help but worry sometimes too.

The tightrope walk of faith continues, through the desert and back to the land of milk and honey on an endless loop, hovering over the darkness of nothingness while at the same time looking to bright infinity above.

One step at a time.

Or as Stipe puts it, “Every whisper, of every waking hour I’m choosing my confessions. Trying to keep an eye on you, like a hurt, lost, and blinded fool.” As my grandmother used to say, “You never arrive.” Day by day, I trust in the sufficiency of Christ’s grace in his sacraments, even when I don’t feel very holy or even interested—which is more often than I care to admit. But then disaster strikes! “The slip that brought me to my knees failed,” Stipe sings. “What if all these fantasies come flaming around?”

Finally, as if an allegorical vision akin to the experiences of medieval mystics, Stipe concludes the song, “That was just a dream, just a dream, just a dream, dream.” Peter Buck’s mandolin carries us out of the song and brings us back to ourselves.

For my part, I wake up and rejoin the Apostles, this time, not in the Upper Room in John 22, but on the mountain in Galilee in Matthew 28. “When they saw him, they worshiped him; but some doubted.”

Oh, life.

Revisit R.E.M.’s thirty-year-old classic, “Losing My Religion,” for the essence of what our beautiful, difficult lives with the resurrected Christ are all about, if we’re honest: a love song.