I was received into the Church in November of 2012 as a convert from atheism. I was just a little too late to be a John Paul II Catholic, knowing him only through the writing I later picked up, and the historical records of the crowds he drew.

But, if I missed him among the great masses, offering Masses, I still was touched by a different sort of gathering he organized, before he was ever a priest, let alone Pope.

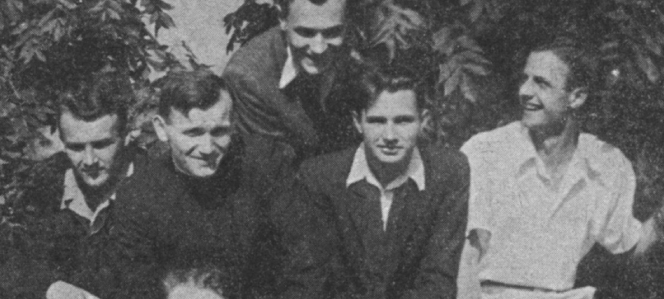

As Karol Wojtyła, he co-founded the Rhapsodic Theater with his theatrical mentor Mieczyslaw Kotlarczyk. The theater wasn’t a physical building but an act of artistic resistance to the Communist occupation of Poland.

The shows that the Rhapsodic Theater staged were offered secretly, in people’s living rooms, out of fear of arrest. The sets were minimal (since they had to be smuggled in and set up amid furniture). Everything was stripped away but the essential: to tell the truth, beautifully.

Even after he entered seminary (this, also secretly), Wojtyła may have given up acting, but he continued writing plays in the spare style he and his friends had shaped out of necessity. I picked up one play he had written during his time as a parish priest, The Jeweler’s Shop, when my husband decided to stage it in what turned out to be a faithful-to-tradition cramped space (a common area of his office).

At first, reading the play, I was put off by the style and the language. Wojtyła’s play is a meditation on marriage, appropriate enough to my circumstances, but the plot unfolds in a series of poetical utterances, not natural dialogue or realistic scenes. It didn’t remind me of Shakespeare, but of the time in college when one of my friends had acted in a play adaptation of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land.

Instead of plot, Wojtyła offered parables. A woman wishing for a divorce tries to sell her ring in the jeweler’s shop of the title, and the proprietor tells her that he can offer her nothing for it. Weighed on its own, with her husband still living, her ring does not move his scale. Their rings must be what they are, united as physical signs of a sacramental grace, to be substantial.

The meaty text is put first, in Wojtyla’s script and in the staging my husband coordinated. For Wojtyła, the elliptical, poetical text demanded to be heard clearly to be understood, and could not be upstaged by too much physical gesticulation and space-filling. And that discipline, as he understood it, was healing to men and women who were drawn by the world into a frenzy of activity, and away from the proper ordering of the eternal over the temporary.

In “Drama of Word and Gesture,” Wojtyła writes that, in the Rhapsodic style:

Man, actor and listener-spectator alike, frees himself from the obtrusive exaggeration of gesture, from the activism that overwhelms his inner, spiritual nature instead of developing it. Thus freed, he grasps those proportions that he cannot reach and grasp in everyday life. Participation in a theatrical performance, almost in spite of him, becomes festive as it reconstructs in him the proportions between thought and gesture that man, at least subconsciously, sometimes longs for.

My husband and I don’t live in a nation as oppressive and hostile to religion as the one in which Wojtyła began writing his plays. But, as Catholics, we recognize that internal agitation that Wojtyła sought to sooth, that rejoices in the festive restorative that theater and poetry can provide.

We gather friends in our home not to avoid the eyes of secret police, but to push back against the small “no’s” to rightly ordered lives that come from our culture (a no to silence, a no to leisure, a no to temperance) and the ones that come from our own temptations and sinfulness (a no to trust in God, a no to awe, a no to welcoming the stranger). It is a smaller, but still heartfelt, resistance.

Last year, on the feast of the Immaculate Conception, we asked friends to bring their favorite art, hymns, and poems about Mary to our apartment to share. If it wasn’t a production in Rhapsodic style, it was certainly a Rhapsodic setting as our friends clustered together, reading their favorite poems out, all of us attentive to the rich and dense texts each person shared.

Before the international crowds, Wojtyła cultivated small oases of beauty and sanity, trusting that his friends and fellow actors could do without almost every staple of the theater, as long as they had text to read that was both beautiful and true. With his writings, and those of so many other witnesses, we always have recourse to this same, simple expression of our hope.