Today, Matt Nelson catches up with Joel Clarkson, an award-winning composer, author, and voiceover performer. Joel has a degree in music composition from Berklee College of Music, a master’s degree in theology, and is currently pursuing his PhD in theology at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. He’s recently finished drafting his first solo book, Sensing God: Experiencing the Divine in Nature, Food, Music, and Beauty, which will be releasing at the beginning of 2021.

In this interview, Matt and Joel talk about the undying importance of human creativity, even in a time of chaos. This conversation is a much-needed breath of fresh air in a time of anger, fear, and frustration. Enjoy!

It says on your website that you can’t recall a time when either music or spirituality didn’t saturate your day-to-day life. Can you tell us a little more about your upbringing and the role that beauty and creativity played in your family’s day-to-day life?

Creativity, beauty, intellectual engagement—these were all part of the background fabric of our home, the sort of foundational aspects already present. We had a library that grew gradually over time, and which we could peruse at will. We always lived in close proximity to nature, and were encouraged to spend time outside getting dirt under our fingernails. Music articulated the rhythms of our day, and we had a piano that was constantly used by one or the other of us kids. We ate delicious homemade meals most nights, and had rousing discussions around the dinner table on any topic of interest.

I think, in a way, our spirituality grew out of that vibrant home world. We were encouraged to connect our enjoyment of nature or music or even intellectual sparring around the dinner table with God’s goodness working itself out as a gift. Before I fully understood Christian faith, before I learned doctrine or theological ideas, the world was given to me as imbued with God’s grace—as sacramental in itself. When it came to scripture or prayer or regular rhythms of worship, we instinctively connected those with the beauty, truth, and goodness already present in our lives.

What were the driving forces behind your decision to become a composer? Has that decision in any way served as a “bridge” to your theological pursuits?

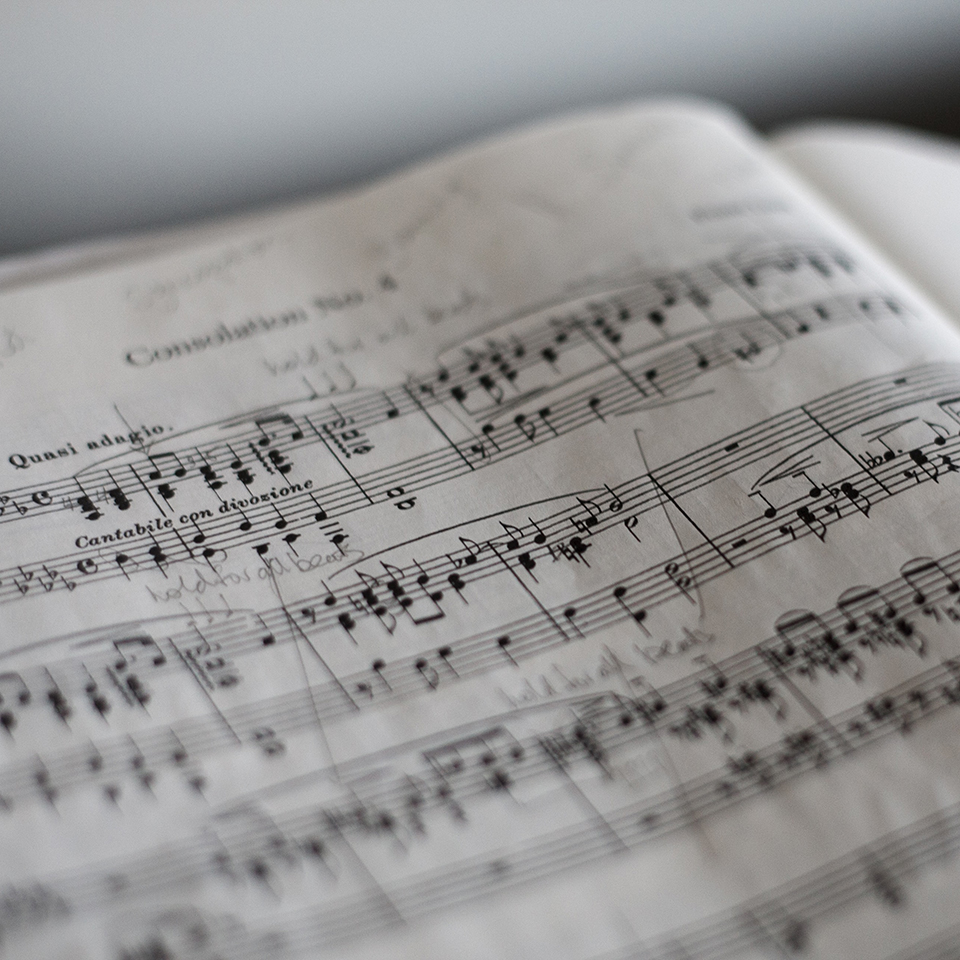

I’m blessed to come from both a very musical and theological family. I’ve had an innate musical ear since I was very young, and though I didn’t receive much formal training in childhood, I spent a lot of time fiddling on the piano (no pun intended). At twelve, I was given a guitar, and soon after started writing songs. My parents recognized my musical capacity and gave me the tools to explore, experiment, and create. I spent a lot of my teen years writing and producing compositions with a basic microphone and recording software. When I eventually went to Berklee College of Music, I was able to pair that love of music with the discipline of harmony, ear training, music notation, and music history. I remember being told by a fellow student that I was going to hate classical counterpoint and harmony classes. To my surprise, when I took the class, I fell in love with writing fugues in the style of Bach! I changed my major to composition, and the rest is history.

After Berklee, I went to Los Angeles to work in film music, and to make a long story short, worked as an orchestrator, while also pursuing opportunities to score films. Along the way, I was privileged to do a set of orchestrations for Joseph Julian Gonzalez’s Misa Azteca, a powerful oratorio engaging with the Catholic mass in both Latin and Spanish, and interspersing it with Nahuatl (Aztec) poetry. I was intrigued by the way the music gave scope to a richer world of meaning around the text, and drew fresh spiritual resonances out of it. Around the same time, while writing music for church choirs, I became captivated by the power of music in worship, and began to realize how the music of the Church contains and expresses its theology in action. Between those two experiences and others along the way, I was compelled to seek a deeper understanding of the relationship between music and theology, which led me to the University of St. Andrews, where I completed a masters in theology and the arts, and am now pursuing a doctorate focused on liturgical music.

Aristotle (implicitly echoing Genesis) wrote that “man is by nature a social animal.” As such, social isolation for many people has felt like its own sort of plague. How might we take advantage of “social distancing” for the sake of creativity, and what role does solitude play in your own life of creativity?

Isolation is a funny thing, because from the outside, I think most of us conceive of it as a sort of dreadful emptiness. For artists, for whom solitude is already necessary for the sake of actually creating their artwork, it might feel even heavier. I wonder if full-time isolation awakens us to realizing how much we artists have learned to treat silence like a utility, something which is only useful insofar as it produces something for us. I know I’ve felt convicted of this often over the past few weeks. The frightening—and yet I think entirely necessary—first step as creative artists in quarantine is to refrain from creating, and simply listen, let the silence introduce itself to us anew. The reason why is that for Christians, silence is never empty, but is precisely the space in which we perceive the Word in the world, speaking to us with that still, small voice.

In my own creative practice during quarantine, at least for a while, I’ve tried to take my own advice of refraining from much new composing, and instead have started recording original choral settings I’ve previously written for liturgy, including a setting of the second-century Marian hymn Sub Tuum Praesidium, and the ancient Maundy Thursday hymn Ubi Caritas. These hymns are prayers in themselves, and have allowed me an opportunity to begin recovering a sense of devotion that, as mentioned above, so easily slips away in the intensity my creative process. I’m also very happy that the process has allowed me to engage with my community as well, by being used in the regular, recorded liturgy of my parish during quarantine.

During the recent lockdowns, a real challenge for families was not so much isolation, but proximation. At the same time it was an opportunity for families to grow closer. You have composed collections of music for “The Lifegiving Home.” Tell us about these projects and how they might be fitting given our current crisis.

The albums were actually written in response to a book by my mother and sister, Sally and Sarah Clarkson, entitled The Lifegiving Home, which lays out a vision for home as a space in which to practice the rhythms of Christian life. I think it’s that notion which is actually at the heart of the crisis we’re experiencing in the “social proximation” you mention. Wendell Berry insightfully discusses the way in which modernity treats the home like it treats everything else, something which is valuable for its utility, but not for its capacity to shape or enrich us. We are taught to function as if home is the exception in our lives, rather than the rule. In that regard, this pandemic has literally flipped our lives inside out; and our relationships are perhaps ground zero for this cultural inversion because we have so few ingrained patterns of what life together looks like when centered around home. Of course, this is also partly compounded by the fact that home, on its own, was never meant to be the sole space of satisfaction in our lives. We were made to be able to work hard, to participate in the liturgy, to cultivate our communities in our churches and neighborhoods. Right now, for many of us, life at exclusively home is a profound culture shock.

This isn’t the ideal in many ways; but I do think our time at home can be a hidden gift, a way of relearning the rhythms of home life. What does this look like? For my quarantine, it’s been homemade meals; daily prayer and time in Scripture; reading, both aloud and alone; enjoying nature; quiet moments for contemplation (and napping); time for substantial conversation; playing and singing music; and much more. Learning practices like these reorients our awareness of the world so that rather than seeing it—and our homes—as something to be consumed and used, we receive them as gifts from God, grace mediated through the mundane.

With this said, I think practicing life at home requires the use of muscles that have largely atrophied, and we should be patient with ourselves (and others) as we grow. I can say that before quarantine, it was a significant mental block for me to think of cooking more than once or twice a week; after six weeks of isolation, I’m averaging about three to four dinners a week, swapping off with my sister Joy, with whom I share a flat. It’s becoming much easier, I’m learning all sorts of recipes and even trying some daring things! There are also wonderful books on good life at home: certainly The Lifegiving Home, and also on a more conceptual level Berry’s The Art of the Commonplace. Robert Farrar Capon’s The Supper of the Lamb is a wonderful book of recipes and reflections on food and spirituality.

Though this is an exceptional time, and we will inevitably reemerge back into the world (as some already are), I hope that we won’t miss the opportunity to use this as a way to reorient our senses, our desires, our practices, and our relationships.

In The Idiot, Dostoevsky famously wrote that “beauty will save the world.” Is there truth to this?

Far be it from me to disagree with Dostoyevsky, and thankfully I don’t have to! As discussed above, the truth at the center of Christianity isn’t an idea or a maxim, or even a doctrine; it is the person of Jesus, who took on flesh—the very tangible stuff of our world—and entered into our reality, our time and space. The Incarnation is, in a sense, a repetition of what God says of his creation in Genesis, that what he has made is “very good”; and through Jesus’ Incarnation, through his enfleshment in our world, it is worth redeeming. In Christ, the source of beauty is revealed in our time and place, and in his Incarnation, our eyes are opened to regard him and seek him in the beauty we encounter in the world around us.

This idea is very much at the core of my recently-drafted first solo book, discussing the way that we come to encounter God through the tangible world around us. It’s entitled Sensing God: Experiencing the Divine in Nature, Food, Music, and Beauty, and will be coming out at the beginning of next year with NavPress. I hope through it to affirm what Christians have believed across the centuries, that through God’s redemptive act of Incarnation, the created world becomes a way to behold God’s glory, and participate in his kingdom work, in anticipation of the time when we will see him, the source and end of beauty, face to face.

Can you recommend three books that have had a great influence on you?

I’ve just recently revisited G.K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday, and found in it the spiritually provoking, gloriously madcap adventure I enjoyed when I first read it as a teen. I think I particularly love how Chesterton so deftly guides us into seeing the wildness and uncertainty of life as the place we most encounter the living God at work in the world (sort of a fictionalized version of what he expresses in Orthodoxy). I think Chesterton more than anyone uniquely expresses that “God’s foolishness is wiser than man’s wisdom.” (1 Cor. 1:25).

On a nonfiction note, Russian Orthodox priest Alexander Schmemann’s For the Life of the World is the rarest of works that is both imminently readable even for the theologically uninitiated, and yet also expresses a full-bodied defense of liturgy and sacrament. It is a wonderful parallel to books like Dietrich von Hildebrand’s Liturgy and Personality, where both are dealing with big themes like Christian personhood, cosmology, and eschatology.

Finally, ending on a note about Christian faith and creativity, I must give a shoutout to Madeleine L’Engle’s Walking on Water. I was able to revisit it while working on Sensing God, and it has so much wisdom about the centrality of the Incarnation to the generativeness of Christian artistry, the relationship between prayer and art, and so much more. An essential read, both for Christians in the arts, and also anyone curious about artistry and regular Christian life.

I suppose that’s actually five books . . . but we’ve got nothing but time on our hands anyway, right? Five books for the price of three—now there’s a good Corona deal!