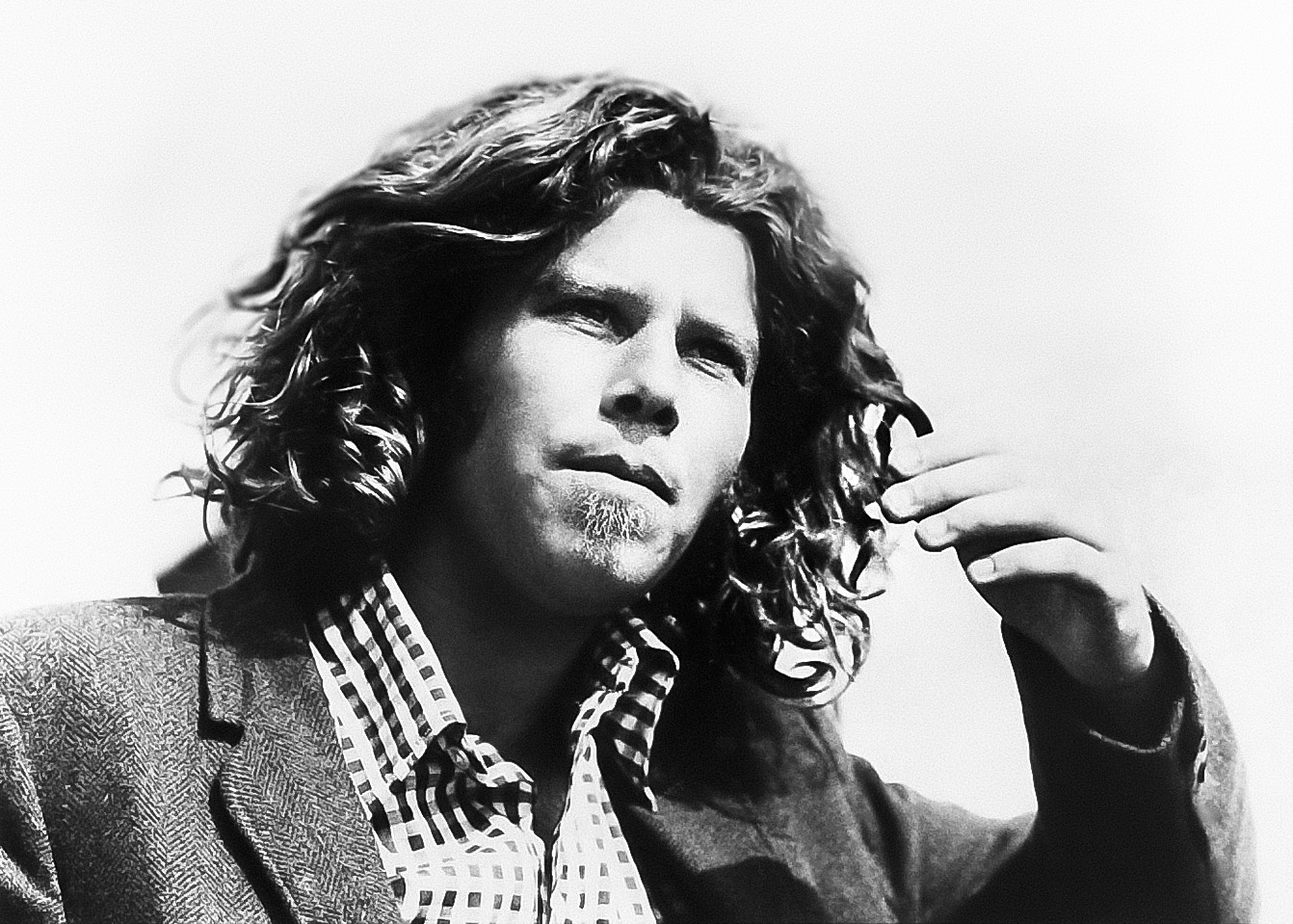

To commemorate the fortieth anniversary of Tom Waits’ first album with Island Records, the label has released remastered editions of all of the albums Waits recorded with them. This includes the distinguished trilogy of albums that cemented Waits’ status as a songsmith with no equal in all of contemporary American music: Swordfishtrombones (1983), Rain Dogs (1985), and Frank’s Wild Years (1987). Representing the turning point in his career, from dwelling in the corners of rundown barrooms and serenading any nighthawks who happened to be drowning their sorrows close by to creating some of the most versatile, inventive, and delightful songs of the late twentieth century, these three albums in particular are treasure troves of fantastical stories, set to scores marked by unique and stunning orchestration, of equal parts majestic and macabre. His songwriting inhabits broken lives and broken hearts with a literary sense derived from the Beat poets and Brothers Grimm alike, and he fills these portraits with a master synthesis of the entire American musical tradition: odes to minstrel shows, vaudeville, opera, ragtime, slave songs, war songs, spirituals, murder ballads, sea shanties, Lead Belly, and Frank Sinatra all appear in the span of a single LP.

Being fruitful and multiplying bears fruit.

Waits himself credits the event of meeting and marrying his wife, Kathleen Brennan, for bringing this turning point about in the first place. Her direct influence on his musical projects, in addition to that of the three children they had together during this period, has been well established. Up until their encounter, Waits’ life was more or less in crisis: his artistic muses had been growing stale, his latest albums were struggling, and his personal demons seemed to have the upper hand. With the presence of Brennan, herself an accomplished musician and songwriter, Waits experienced rapid personal and artistic renewal, which was only enhanced with the growth of a family. This event has proven undoubtedly to have initiated Waits’ ascent from mere cult figure to musical legend.

The revived attention to this event and the incredible albums that proceeded from it warrant extended reflection. St. Maximilian Kolbe, in a separate context, said that only love is creative. At the risk of redundancy, Tom Waits’ album trilogy in the mid-eighties displays creativity par excellence, containing the most unique sounds and stories one might find anywhere in music. It may only be coincidental that Waits married and had children at the same time that he made these albums, but it is rather probable that his new life as a husband and father served as an abundant font of originality. The self-abandonment of a person to a life dedicated to another’s good in the sacred bond of matrimony bears fruit unlike any other human endeavor. An obvious instance of this is perhaps the most original thing that a human person can do: participate in the creation of a child and raise the child in the love of a family. Anyone who has spent even a brief period playing with a child understands the power of an untamed imagination, and if an adult is willing to suspend his pretensions and enter into a child’s world and experience, he will likely find that this engagement can yield entire vistas into reality that would otherwise be totally impenetrable. And that encounter has the potential to be radically invigorating.

A personal anecdote might be appropriate here. In learning to play with my one-year-old daughter, I have discovered that the limits normally imposed in other situations of play—say with a ten-year-old or a teenager who has developed physical skills like walking and running and jumping and speaking and voicing his preferences for what he wants to do—are out of the question in this particular circumstance. Because my child has yet to find out what she is capable of, she appears to be far more interested at the moment in what I am capable of and has consequently given herself over to the movements of whim. And I have learned that the more I give myself over to the movements of whim, the more we are both enriched by our play together. This has brought forth a number of pleasant results. For one, the juggling skills that I learned in high school, but abandoned in college, have returned in full force, revealing new tricks that I had never conceived of. My singing, or rather the doggedness with which I sing, has increased exponentially as I become more comfortable with my voice cracking and finding new ways to sing old songs for one who has never heard them. My child’s toys have become my toys as well, and my ability to play with them, through use of my own imagination, has deepened, much to her delight and mine. All of this creativity was, in a sense, coaxed out of me.

Tom Waits was also a new parent while he made this trilogy of albums, and the spirit of that distinct parental surrender abounds. For the first-time listener, the music is downright strange, tone-deaf, and almost not like music at all. At times it sounds just like a toddler is playing the piano or the tuba or the xylophone or the accordion for the very first time. However, with a persistent openness and a devoted ear, one may discover a deep, interior chord in his soul struck by the music’s disarming beauty. Much of its power to disarm is due indeed to its playful and childlike qualities. Waits and his studio musicians, surprisingly meticulous craftsmen, attack these compositions without an ounce of shame or fear, conceding to their imaginative yearnings with joy.

This idea of a creative wellspring runs well athwart the conventionally lauded narratives of inspiration. The common example of such a narrative is the 27 Club, which surrounds artistic legends like Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison with a mystique cultivated by drug and alcohol abuse, rampant sexual pursuits, and thoroughly unkempt lives. The notion of an artist diving headlong into the sober demands of marriage and parenthood is, at the very least, incongruent with that kind of narrative. But the life of Tom Waits and the immense value of his music during the “Island Years” make a solid case for artistic creativity born out of love. To put it another way, being fruitful and multiplying bears fruit.

Our time seems to be marked by a craving for new wine in new wineskins within the realms of art. One possible solution could be to retrieve notions of inspiration, like the kind Tom Waits retained, that have been forgotten and neglected for so long that, when presented in all of its vitality to a hungry culture, turn out to be a source of new wine all the same. After all, it was in the context of matrimony that someone commented, “You have kept the good wine until now” (John 2:10).