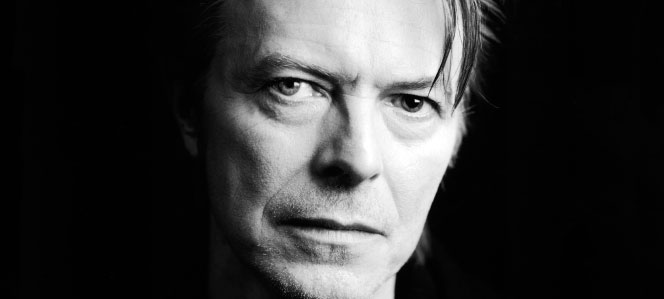

For the past few months, I have been teaching religion class on Monday nights at a parish in the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan. Recently, I found out that the church was right next to the home of the late rock-star David Bowie. Although I never saw him myself, I heard that he lived an unassuming life there, frequenting local cafes and bookstores.

Two days before he died, Bowie’s last album Blackstar was released. It is being described as his “sung epitaph”, his great artistic farewell. He produced the album knowing that his cancer was terminal, and it is full of themes of mortality and death, especially the song Lazarus. I watched its music video with a priest who remarked, “Here you see pop culture touching the eschatological.” Having watched it several times since, I find myself agreeing with him more and more: even in the somewhat pagan art of David Bowie, one can see a soul grasping for truth.

Haunting Awareness of Death

The Lazarus music video begins showing a frail David Bowie trapped in a dark hospital room. The music is eerie avant-garde jazz, punctuated with ominous sax and trombone riffs. A dark figure under his bed reaches towards him as Bowie anxiously recognizes his approaching death: “Look up here, man, I’m in danger!”

The next scene shows a more energetic David Bowie in a room with a wardrobe, dancing in way that recalls the performances of his youth. He sits at a desk to write out his last creative inspiration, aware that he is racing against the clock. As time ticks away, he writes more and more frantically, just barely finishing before Death beckons and he exits the scene.

The video is packed with meaning, but what caught my attention before anything else were the numerous memento mori. The most obvious are the hospital room and the mysterious figure beneath the bed (a weird version of the Grim Reaper). Another is a skull that sits upon Bowie’s writing desk. Also evocative of death is the dancing Bowie’s skeletal costume, as well as the way he jerks like a wind-up toy reaching the end of its short kinetic life. The most dramatic (in my opinion) is the coffin-like wardrobe into which Bowie closes himself at the end of the song.

Seen as a whole, Lazarus is itself a great memento mori, a vivid reminder of the certainty of death and the fleetingness of life. A man who had it all – fame, money, and glamour – recognizes and embraces the fact that he will soon lose it all in death.

Lazarus strikes me as a sort of musical vanitas, an artistic reminder that Death awaits everyone without exception, and thus all earthly things are “vanities of vanities.” In particular, it calls to mind a Dutchvanitas that I saw last week in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work by Pieter Claesz (1596/97–1660), shows a skull on top of a book and a quill, recalling to the viewer the ephemeral nature of personal production. No matter how much or how well one writes in the book of his life, sooner or later, Death decides the final chapter.

In turn, the smoldering candle in the Claesz painting reminds me of a great literary vanitas by Shakespeare, coming from the mouth of a desperate Macbeth:

…Out, out, brief candle!/ Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,/ That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,/ And then is heard no more.

Glimpses of Hope

Battling with terminal cancer, David Bowie must have known during his performance in Lazarus that “his hour upon the stage” was coming to a close. Like Shakespeare and the great artists of thevanitas genre, Bowie was well aware of the inevitability of death, and he expressed this awareness as only an artist can.

Most of us are familiar with Bowie’s life and know that, like many rock stars, he was was no paragon of moral virtue, and much of his art was morally questionable at best or downright blasphemous at worst. But despite all of this, he was nevertheless very human – he was searching for hope and meaning in a world that often denies both. Throughout his song, hopeful glimmers pierce through the darkness, especially the beginning and ending verses that serve as reassuring bookends.

The opening verse: “Look up here, I’m in heaven!”

And the final verses:

Oh, I’ll be free/Just like that bluebird/Oh, I’ll be free!/Ain’t that just like me?

Bowie’s swan song expresses the very human angst that we all experience when confronted with death and the fleetingness of life, but it also shows the hope that the end of life is just the beginning of a better one. The title itself calls to mind the great episode of John 11 when Jesus Christ proclaims himself “the resurrection and the life” and raises his friend Lazarus from the dead.

We can take heart from this artistic glimpse of hope that David Bowie left us, as well as from these words that his wife wrote on Instagram shortly before the news of his death broke: “The struggle is real, but so is God.”