For Richard Linklater, it’s all about the mystery of the moment—“the holy moment,” as one character says in Waking Life. From the quiet rapture of Before Sunrise to the raucous energy of School of Rock, the longtime independent filmmaker’s work looks at the small encounters between family, friends, and sometimes even strangers that can shake up our whole world, taking us beyond the façade of civility to a place of unadulterated honesty and intimacy.

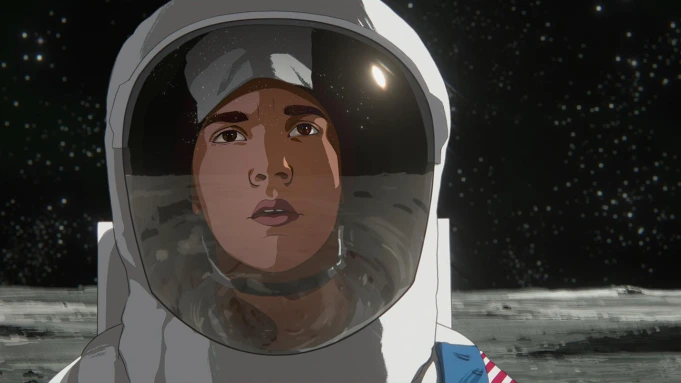

Linklater’s latest film, Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, brings the animated style of Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly to a more straightforward coming-of-age story. It is the summer of ’69 in Houston, and Stanley, a fourth-grader and the youngest of six, is processing the social, political, and cultural data of the rapidly changing world around him: hippies, push-button phones, Jiffy Pop, duck-and-cover drills, sci-fi films, DDT trucks, rock and roll, drive-ins—and of course, the forthcoming moon landing. Stanley is tapped by NASA for his own secret mission to the moon—one that, as it happens, unfolds on the edges of sleep.

Linklater deftly draws out the universally relatable experiences of childhood that never go out of style: the games, the dreams, and of course, the family. But here, the holy moment is an intimate encounter with a lost moment in time. What results is a nostalgic tour through various cultural artifacts and experiences of the late ’60s sure to resonate in a special way with Baby Boomers.

Amid all of the markers of that time and place, though, there is one tossed-off line that might be especially interesting to younger generations. Stanley recalls in a voiceover: “I learned later that after I was born, my mom got on this new thing called the pill, but never told our priest, for fear of being excommunicated.” The camera then cuts to the lawn next door and the big family lined up on it. “Then there were our next-door neighbors, the Pateks, who were clearly not using contraception because they were still kickin’ out a kid about every year.” This scene, like much of Apollo 10½, appears to be autobiographical. In a 2013 article, Tim Teeman notes that Linklater is “a lapsed Catholic, after his mother told the Church to ‘[blank] off’ when it stopped her acquiring birth control.” (Linklater adds: “I’m so grateful not to have grown up in that guilt-riddled world.”)

And thereby hangs a tale. On the face of it, the arrival of—and resistance to—artificial contraception appears to be as much a part of our cultural past as the Star Spangled Banner playing at midnight. Since the ’60s, contraception has become the widely accepted and practiced norm, including among Christians. Artificial birth control was something like the social equivalent of the mad dash to the moon; it inaugurated the “spacing age.”

But in reality, we are still living out its arrival. The “new thing” of artificial contraception was not just the turning point between an “old America” of big families that exists now only in memory (or film), and a new America where two or three kids is the acceptable max and the childfree life is rather ideal. It is, in many ways, the turning point between traditional beliefs about sexuality and the era of increasing sexual liberalization: second-wave feminism, no-fault divorce, abortion on-demand, gay marriage, polyamory, the pornography industry, the transgender movement. The uncoupling of sex and procreation in the marriage bed was the cultural earthquake that led to the tsunami of ever-receding sexual boundaries in which we’re now living.

And we are still living in its resistance—at least, where the Catholic Church is concerned. The Linklaters’ story is a typical snapshot from this period in the Church, where there was a lot of confusion and mixed messaging on precisely this issue. There was mounting expectation that the Church would lift the ban of contraception, especially after a majority report from a papal commission, which supported that lift, was leaked to and published in the National Catholic Reporter in 1967. But in 1968, Pope (now Saint) Paul VI courageously sided with the minority and—almost a year to the day before the moon landing—issued Humanae Vitae, the Church’s definitive upholding of its teaching. A whirlwind of open dissent from laity, priests, and even bishops erupted in its wake, and it rages on to this day in the arena of sexuality. Yet the Church continues to honor both the unitive and procreative significance of sex, insisting instead on natural methods of spacing children when there is serious reason to do so. Its ban on contraception remains an important key to unlocking the whole of its moral teaching, predicated on the self-gift that makes love true.

None of this is the focus of Apollo 10½, of course, which is really just a simple, sentimental movie about a young boy in the ’60s dreaming of going to the moon. But the scene raises a question: Is the Church just a weird, guilt-ridden, hidebound, male-dominated institution that missed the revolutionary boat and is stuck in the ’50s? Or is it interested in the things that never change, because they never can change—the integrity of the holiest of moments and the most intimate of encounters?

For many, the question answers itself. But as our society suffers from the fallout of the sexual revolution predicted by Paul VI, moves more and more away from hormonal and chemical quick fixes with hidden risks toward more natural alternatives, and looks ahead to a post-Roe future many thought could never happen, the answer is perhaps not so obvious. Our demographic shift further complicates the old narrative: in NASA’s heyday, there was great anxiety over the “population bomb”; now, none other than SpaceX founder Elon Musk is warning of the opposite threat of a population implosion.

Perhaps the spacing age equivalent of going to Mars will come through rediscovering the home.