Over the past few weeks, Americans learned (mostly for the first time) that “2,342 children have been separated from their parents after crossing the Southern U.S. border.” Naturally, this led to a lot of outrage. Initially, President Trump blamed Democrats for the “horrible law” leading to this, but as it largely related to of his own Administration’s zero-tolerance immigration policy (dating back to April of this year), he eventually backtracked and signed an executive order shifting the policy from one of family separation to one of family detention (while still leaving authorities the power to separate families for the sake of the child, when circumstances demand). Thanks be to God, that seems to be a generally-good solution to the problem, and one that makes nearly everybody happy…except that it didn’t (at least immediately) lead to any relief for the thousands of children currently separated from their parents.

One of the most troubling things the recent debate on immigration brought up was how quickly social conservatives simply shrugged at the problem, with excuses like: “Obama did it, too!”, “abortion is a bigger issue,” etc. Typically, these weren’t points raised to further the conversation but to end it by deflection. Ultimately, all this served to do was to undermine the pro-life cause. When pro-lifers only seem to care about the well-being of children when it’s politically expedient for Republicans or for President Trump, the message the rest of the world hears isn’t “Wow, they’re right, abortion is a bigger issue,” but “these people don’t really care about kids as much as they care about their party.” That may not be the case, but that’s the message this kind of “but abortion!” deflection sends.

To be sure, I completely understand why social conservatives are in no mood to be preached to about taking care of children by liberals who support abortion. But now you get how the other side feels, too. Both sides are (understandably) disgusted with the other for an apparent lack of principles, even on something as important as whether we should protect children. For decades, the Soviets would deflect criticism of their (abysmal) human rights record by responding, “And you are lynching Negroes.” And they were right: America had a serious problem with lynchings during these decades. But that deflection didn’t make the Soviets’ own hands any cleaner.

I. Children Have a Right to Their Mother and Father

The solution here, it seems to me, is to simply stop the partisan bickering and score-keeping and instead talk about principles. All of us, conservative or liberal, religious or irreligious, should be able to agree to the following basic principle: “Children have a right to grow up in a family with a father and a mother capable of creating a suitable environment for the child’s development and emotional maturity.” That’s from Pope Francis’ opening address to the Humanum Conference in 2014. As you’ll see, figures from all over the political spectrum agree with this…as does a wealth of social science. So does the United Nations, in the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which holds that “children also have the right to know and, as far as possible, to be cared for by their parents.”

But why should we care about this at all, especially if we don’t have children ourselves? For the good of the children, obviously, but also because the well-being of the family matters to society, and the well-being of society matters to the family. Pope Francis put it this way:

The crisis in the family has produced an ecological crisis, for social environments, like natural environments, need protection. And although the human race has come to understand the need to address conditions that menace our natural environments, we have been slower to recognize that our fragile social environments are under threat as well, slower in our culture, and also in our Catholic Church. It is therefore essential that we foster a new human ecology.

So just like the influx (or death) of a particular species would totally change its natural environment, if the family is dying, the surrounding environment suffers. So if we care about the well-being of society, it’s good to focus on the family. In a recent essay, Mary Eberstadt recalled the social scientist James Q. Wilson’s warning from 1997:

Children in one-parent families, compared to those in two-parent ones, are twice as likely to drop out of school. Boys in one-parent families are much more likely than those in two-parent ones to be both out of school and out of work. Girls in one-parent families are twice as likely as those in two-parent ones to have an out-of-wedlock birth. These differences are not explained by income….children raised in single-parent homes [are] more likely to be suspended from school, to have emotional problems, and to behave badly.

We now stand two decades and “many more books and scholars and research studies later,” only to find that “a whole new wing has been added to that same library Wilson drew from, all demonstrating the same point he emphasized throughout his speech: The new wealth in America is familial wealth, and the new poverty, familial poverty.”

Sociologists like W. Bradford Wilcox and Mark Regnerus are famous (and infamous) for compiling this data, but I am intrigued by a much less expected source: the New York Times. The piece is entitled “Extensive Data Shows Punishing Reach of Racism for Black Boys,” but the data presented is actually more nuanced. Of particular note is the role of fathers (in particular) within the community:

The authors, including the Stanford economist Raj Chetty and two census researchers, Maggie R. Jones and Sonya R. Porter, tried to identify neighborhoods where poor black boys do well, and as well as whites.

“The problem,” Mr. Chetty said, “is that there are essentially no such neighborhoods in America.”

The few neighborhoods that met this standard were in areas that showed less discrimination in surveys and tests of racial bias. They mostly had low poverty rates. And, intriguingly, these pockets — including parts of the Maryland suburbs of Washington, and corners of Queens and the Bronx — were the places where many lower-income black children had fathers at home. Poor black boys did well in such places, whether their own fathers were present or not.

“That is a pathbreaking finding,” said William Julius Wilson, a Harvard sociologist whose books have chronicled the economic struggles of black men. “They’re not talking about the direct effects of a boy’s own parents’ marital status. They’re talking about the presence of fathers in a given census tract.”

Other fathers in the community can provide boys with role models and mentors, researchers say, and their presence may indicate other neighborhood factors that benefit families, like lower incarceration rates and better job opportunities.

That doesn’t mean that racism doesn’t play a role, or that fatherless families are the only problem facing African-American males. Indeed, some of those other factors—like mass incarceration—directly play into the problem of missing fathers. So the situation is more nuanced (not less) than the Times’ headline let on. But very near the heart of the question is a reminder that family matters, not just for the nuclear family, but for the whole community. The dissolution of a family isn’t just a purely private affair. And this seems to be part of why these researchers had such a hard time finding well-functioning African-American communities. As the Times’ accompanying graph shows, only about 4% of poor black kids live in “father-rich” environments, compared to 63% of poor white kids.

But nevertheless, the statistics speak for themselves, as President Obama acknowledged boldly in a 2008 Father’s Day address at the Apostolic Church of God in Chicago:

Of all the rocks upon which we build our lives, we are reminded today that family is the most important. And we are called to recognize and honor how critical every father is to that foundation. They are teachers and coaches. They are mentors and role models. They are examples of success and the men who constantly push us toward it.

But if we are honest with ourselves, we’ll admit that what too many fathers also are is missing—missing from too many lives and too many homes. They have abandoned their responsibilities, acting like boys instead of men. And the foundations of our families are weaker because of it.

You and I know how true this is in the African-American community. We know that more than half of all black children live in single-parent households, a number that has doubled—doubled—since we were children. We know the statistics—that children who grow up without a father are five times more likely to live in poverty and commit crime; nine times more likely to drop out of schools and twenty times more likely to end up in prison. They are more likely to have behavioral problems, or run away from home, or become teenage parents themselves. And the foundations of our community are weaker because of it.

The fact that figures as varied as the conservative Eberstadt and liberal Obama are sounding the same alarm about fatherless communities should give us pause. When people like The Nation’s Mychal Denzel Smith responded to Obama’s speech by mocking “the dangerous myth of the ‘missing black father,’” they did so simply by turning a blind eye to a wealth of data on both the widespread problem of fatherless families and fatherless communities.

II. What This Implies

Maybe everything I’ve written so far seems uncontroversial. After all, who would want to deprive a child of their biological mother and father, absent some extraordinary reason like abuse?

And yet, we’re a nation with no-fault divorce, in which the parents’ happiness is permitted at the expense of the child’s well-being and future development. Or to take a more extreme example, we’re a nation in which IVF and gay adoption are legal and almost uncontroversial, in which, from the very beginning, we intentionally deprive a child of her biological parents for the sake of the adults who can afford the procedure. In these ways, we both subvert the rights of children and risk treating them like commodities rather than human beings.

Even attempting to speak out on this can backfire, as the fashion designer Domenico Dolce (of Dolce & Gabbana) found out in 2015. He came out against IVF on the grounds that it’s unnatural and that a child needs a mother and a father. When asked whether he wanted to be a father, Mr Dolce said: “I am gay. I cannot have a child. I don’t believe that you can have everything in life.” Elton John (who has two children through IVF) led a boycott against Dolce & Gabbana until Dolce was finally forced to apologize.

Of course, it doesn’t stop there. All sorts of practices in the modern West—from widespread pornography to the growing length of the workweek—work against the health and well-being of the family and of children. Taking our rhetoric about children seriously should actually cause us to reevaluate our policies and politics.

III. The Hard Cases

The idea that a child has a right to a mother and father obviously isn’t absolute in at least one sense: parents can die. But what about other causes? What about when parents give kids up for adoption, or when families are separated because of abuse or other factors? And to get squarely back to the question at the heart of the recent immigration debate: How do we make sense of a child’s right to a father or mother if that parent breaks the law?

As a a general rule, the question ought to be: will the child (and society) be more helped or hurt by this separation? When a single teenage mom decides to give up her baby for adoption, that’s usually a selfless act of love, and the harm of the child not knowing his or her biological parent (and make no mistake, that is a pain that child will have to grapple with) is hopefully off-set by the child having a greater opportunity to grow up in a healthy familial environment. In the case of married couples’ separating, the Catholic Church’s stance is that:

If either of the spouses causes grave mental or physical danger to the other spouse or to the offspring or otherwise renders common life too diffcult, that spouse gives the other a legitimate cause for leaving, either by decree of the local ordinary or even on his or her own authority if there is danger in delay.

So the Church recognizes that, yes, there are cases in which a family being all together under one roof might be a nightmare rather than the ideal.

But maybe the hardest cases of all are when a parent is a nonviolent lawbreaker. Should they go to jail for the sake of society? Or not, for the sake of their families? We saw this tension in an obvious way recently, but I want to turn your attention to a fascinating proposal. Professor Paul Butler, a former prosecutor for the District of Columbia, now argues that “there is a tipping point at which crime increases if too many people are incarcerated. The United States has passed this point. If we lock up fewer people we will be safer.” He offers three reasons: that it disrupts families, creates too many unemployable young men (since few employers are willing to take a risk on an ex-con), and that it turns jail into a “rite of passage,” thereby decreasing respect for both the law and law enforcement. In particular, Butler takes aim at the shockingly high number of people imprisoned for nonviolent drug offenses. This epidemic of incarceration is no small part of the story of how we ended up with two-thirds of poor black kids growing up in communities with few father figures. An imperfect father is (typically) better than no father, and that’s as true for the broader communities as it is for the immediate family. So at least sometimes, the pro-family solution (and the way of best protecting the common good and public interest) might be not punishing to the fullest extent of the law.

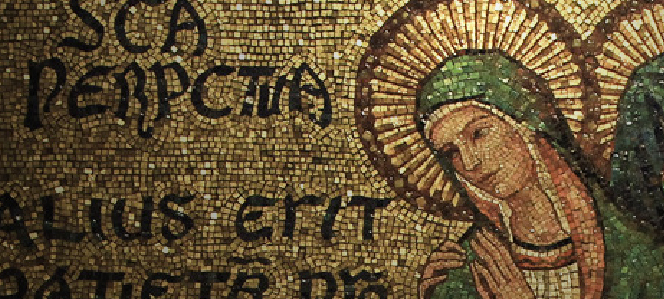

A good saint to turn to is St. Perpetua, who was imprisoned—and separated from her baby—on account of being a Christian. She testified: “I was frightened, because I had never experienced such darkness. Oh, what a terrible day: the strong heat because of the crowd, the extortion of the soldiers! Worst of all, in that place, I was tormented by worry for my infant.” (A fuller account of her martyrdom can be found here.) It’s a striking witness that what hurt her the most is to be separated from her baby. So as the family continues to suffer a thousand different attacks, St. Perpetua, pray for us!