It’s no wonder Italy is one of the most captivating places on earth—there’s a cultural premium placed on keeping things looking good. Word on Fire blog contributor Father Damian J. Ference explores the upsides to the idea of “bella figura,” but also how we must look beyond it for true spiritual growth and healing.

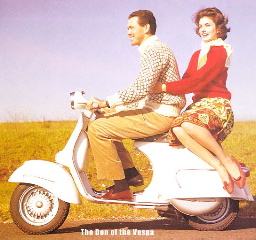

The Italians have a saying that I learned a few years back while visiting a priest friend in Rome—bella figura. Literally, bella figura means “beautiful figure,” and you see it everywhere you go in Italy. Italian men and women tend to dress well, and everything about their appearance seems to be put-together. They look good no matter what they are doing—their clothes fit, their hair is styled, and even if the men haven’t shaved in a couple days, the look is intentional, like a model—beautiful figures.

You also notice the bella figura when you go shopping. There’s a great little religious goods store just around the corner from St. Peter’s Square where I like to buy quality gifts for good friends when visiting Rome. It usually takes me five or ten minutes to figure out what I want to buy, but once I let the ladies who run the store know that I’ve decided on a few items, that’s when the real fun begins. The storeowners want to make my gifts look good. Pragmatism and efficiency are mocked by the bella figura, as the women literally spend as much time wrapping my gifts as I spent finding them. And when all the wrapping is done, my purchases are gently placed into a very fine looking bag with the store name written across it, so that I look good as I walk back to my hotel.

Of course, the bella figura is perhaps on display most when you go out for a meal. There is no early-bird special in Rome. Most good restaurants don’t start serving dinner until seven o’clock. To demand a restaurant to open early, or to rush through a meal is bad form, or manifests the very opposite of bella figura, which is brutta figura—“ugly figure.” Notice that bella figura is not just about physical appearance, but it also encompasses social behavior as well. The bella figura holds that there are some things that you simply don’t do because they go against what is aesthetically pleasing, culturally appropriate or socially acceptable. An example is in order.

Two years ago I joined four priest friends for the closing celebrations of The Year of the Priest in Rome. One night we were out to dinner and all of us ordered seafood pasta for our first plate. Now in Italy, Italians think it is brutta figura to put cheese on seafood—pasta with marinara or meat is not a problem, but for some reason they get irritated when you sprinkle parmesan cheese on seafood. When our seafood pasta arrived, I heard one of my priest friends (who puts cheese on everything) ask the waiter, in Italian, for some cheese. But here’s the kicker—my priest buddy assured the waiter that the cheese wasn’t for him, but for the Ugly American sitting across from him, which was me! Having lived in Rome for four years, my friend was willing to throw me under the bus so he wouldn’t look bad asking for cheese, even though he wanted the cheese for himself. He was concerned with his bella figura, but obviously not mine.

There is something about the bella figura that is right and good. It is true that if you dress the part, it is easier to play the part. Even if you don’t feel like going to work because you are tired or feeling under the weather, forcing yourself to shave, shower, get dressed, brush your teeth, and comb your hair helps you do what needs to be done, and to do it well. Think too of our homes, hospitals, offices, stores and churches. We want the places that are visible to the public to look beautiful and ordered. In a very real way, such beauty and order reflect God, and there is something about reflecting God that makes us more God-like.

And there is something very commendable about protecting social custom with good behavior and appropriate action as well. We want our institutions, businesses, schools, sports teams, churches and our own families to uphold the bella figura to a certain degree, because although we know that no institution and no family is perfect, we tend to hide our flaws and foibles rather then put them on display for the whole world to see, because some things need not be shared.

And there is something very commendable about protecting social custom with good behavior and appropriate action as well. We want our institutions, businesses, schools, sports teams, churches and our own families to uphold the bella figura to a certain degree, because although we know that no institution and no family is perfect, we tend to hide our flaws and foibles rather then put them on display for the whole world to see, because some things need not be shared.

But here is where the danger creeps in. There is room for the bella figura in the life of the Christian, but we must be careful, because in the spiritual life, conforming to the bella figura can spell disaster.

At the very heart of Christianity is the belief that we are a fallen people in need of a Savior, and that God loved us enough to send his only Son to save us. In other words, Christianity is not self-help religion. The way to salvation is not found in us but in God. Therefore, the first step in the spiritual life is to recognize that we need help—that something is wrong with us and that we can’t fix it.

Ask anyone who is involved in a twelve-step program and they will tell you that the first step to healing is admitting that you are sick, that you are powerless, and that you need God to save you. This admission that we are not self-sufficient is a foundational principle of Christian spirituality. Christ can’t save us if we don’t want to be saved, and he can’t help us if we pretend that we don’t need his help. Yet this is a major trap that we tend to fall into—we try to hide our brokenness, our pain and our weakness and we do everything in our power to make ourselves appear healthy and whole—we spiritualize the bella figura.

Consider the gospels. Who were the folks that were most open to the healing and redeeming power of Jesus? They were the ones who knew that they were sick, the men and women who realized they could not fix or save themselves – the man born blind, the woman caught in adultery, the leper, the man with the withered hand, the hemorrhaging woman, and the paralytic. When they exposed their woundedness and their ugliness to Jesus, he did not exploit or embarrass them, but rather, he healed them and restored their dignity with his compassionate love—he saved them.

Consider the gospels. Who were the folks that were most open to the healing and redeeming power of Jesus? They were the ones who knew that they were sick, the men and women who realized they could not fix or save themselves – the man born blind, the woman caught in adultery, the leper, the man with the withered hand, the hemorrhaging woman, and the paralytic. When they exposed their woundedness and their ugliness to Jesus, he did not exploit or embarrass them, but rather, he healed them and restored their dignity with his compassionate love—he saved them.

And this is precisely why the Lord struggled so much with the scribes and Pharisees, because they spent so much of their time trying to appear righteous, wedded to the bella figura, that they were unable to recognize their own brokenness and present their need for healing to Jesus. They were upset that Jesus ate with sinners and tax collectors, but were blind to their own sin. Note how Jesus diagnoses their problem as the spiritual bella figura: “Woe to you scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you are like the whitewashed tombs, which outwardly appear beautiful, but within they are full of dead men’s bones and all uncleanness.” The scribes and Pharisees thought that the point of religious life was to keep your nose clean, follow the law, and look good, when in reality, the point of religious life is to allow the Incarnate Law to redeem you.

And this is precisely why the Lord struggled so much with the scribes and Pharisees, because they spent so much of their time trying to appear righteous, wedded to the bella figura, that they were unable to recognize their own brokenness and present their need for healing to Jesus. They were upset that Jesus ate with sinners and tax collectors, but were blind to their own sin. Note how Jesus diagnoses their problem as the spiritual bella figura: “Woe to you scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you are like the whitewashed tombs, which outwardly appear beautiful, but within they are full of dead men’s bones and all uncleanness.” The scribes and Pharisees thought that the point of religious life was to keep your nose clean, follow the law, and look good, when in reality, the point of religious life is to allow the Incarnate Law to redeem you.

As the Church, the body of Christ, we are at our best when we see ourselves for who we are—fallen men and women in need of a savior. As St. Paul says, it is in our weakness that we are strong. We don’t have to look too far back to see how covering up our sins has hurt us as a Church. And I’d be willing to bet that most of us don’t have to look too far back in our personal lives to recognize that the bella figura is an enemy to the spiritual life.

As the Church, the body of Christ, we are at our best when we see ourselves for who we are—fallen men and women in need of a savior. As St. Paul says, it is in our weakness that we are strong. We don’t have to look too far back to see how covering up our sins has hurt us as a Church. And I’d be willing to bet that most of us don’t have to look too far back in our personal lives to recognize that the bella figura is an enemy to the spiritual life.

Because of all this, it seems to me that one of the most important prayers in the life of the Christian, especially those of us who have fallen into the trap of the spiritual bella figura, is the Jesus Prayer—“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” That’s where healing and salvation begin.

Rev. Damian J. Ference is a priest of the diocese of Cleveland. He is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy and a member of the formation faculty at Borromeo Seminary in Wickliffe, Ohio. He is the newest Word on Fire blog contributor.