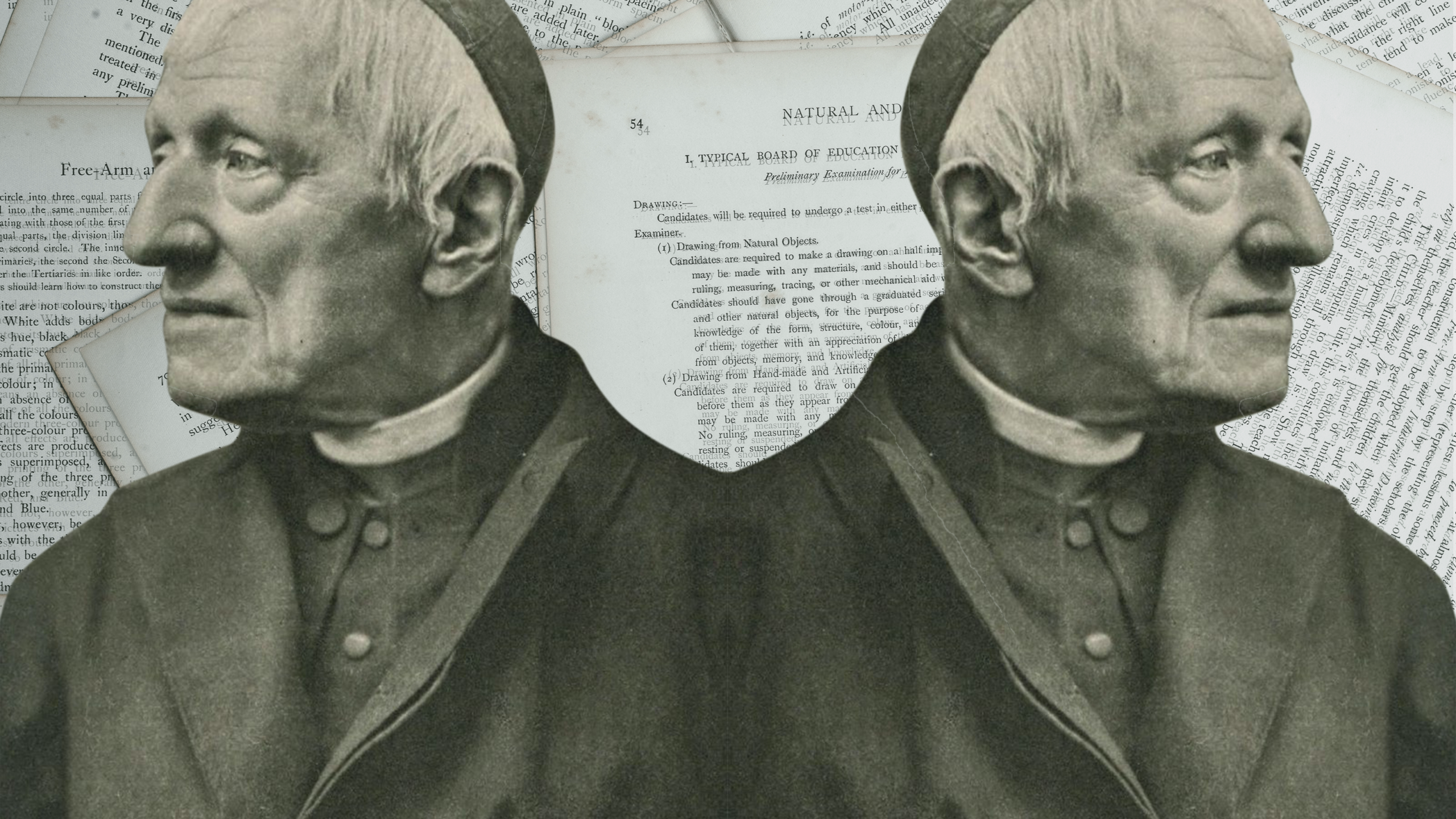

Since the canonization of John Henry Newman, there have been occasional suggestions, particularly on social media, that the Anglican convert might be embraced by some, particularly by more progressive sorts, as “the patron saint of dissenters.” Newman’s willingness to launch his spacious intellect into debate within the Church is almost glamorous to contemplate, but it remains true that what some call his dissent, honed by his openness, was always exercised in full conformity with the Church’s teaching and grounded in loyalty—and hence, cannot be characterized as genuine “dissent.”

Intellectual rigor and loyalty are not mutually exclusive; what Newman models for the modern Church is, perhaps, a willingness to apply one’s own conscience and intellect to any question with enough openness as to leave room to be surprised at one’s own conclusions.

In that sense, Newman is hardly the first prominent Catholic to wonder “Yes, but . . . ” and then nevertheless fall prostrate in loyal obedience. The Servant of God Dorothy Day was able to reason with such openness, and yet she self-identified as “an obedient daughter of the church.”

Reasonable Catholicism is a kind of reasoned loyalty, or sometimes even loyalty with gritted teeth; it is loyalty that insists upon the application of reason, lest its value be questioned. By the same token, intellectualism that is not tempered with loyalty ends up pickling itself in its own ego. Either one, by itself, is incomplete. Both are required.

Intellectualism that is not tempered with loyalty ends up pickling itself in its own ego.

This openness to consider all possibilities rather than rejecting a thing outright (or embracing it without thought) is the difference between reading Paul’s eyebrow-raising words to Timothy that women “will be saved through childbearing, provided they continue in faith and love and holiness, with modesty” (1 Tim. 2:15) and either rejecting them outright as the discriminatory and archaic utterances of a misogynistic patriarch or grimly trying to conform to the stricture without question, which may also mean without understanding and possibly without charity.

But believing that nothing in Scripture is accidental, Catholics are obliged not to sneer but to wonder about the theology behind Paul’s words and to discern what in that surprising verse is worth pondering in an era when human life is held cheap. Can we discern within the verse a notion that women are, in God’s sublime and mysterious mercy, privileged in their ability to assist God in his continual re-entering into our world, disguised as he is within that helpless, vulnerable, and unconditional love that instantly forms between mother and child, father and child, siblings, and grandparents and child?

If we can openly allow ourselves to reason upon the foundational stipulation that God wants only our good, we can surprise ourselves with our conclusions. Suddenly “misogyny” looks like an expedient and human explanation, and blind obedience looks so unsatisfyingly empty; the whole verse is suddenly fraught with a deeper, holier, and ultimately more idealistic meaning than either the intellectualist or the unquestioning loyalist could have imagined.

When intellectualism and loyalty are open to each other, all understanding is enlarged.

The Church is egalitarian in whom she regards as holy; the canon of saints includes the highly educated Augustine and the loyal little bourgeoisie known as Thérèse, and it calls both of them Doctors of the Church. She recognizes that intellectual gifts are only remarkable because they are, in fact, gifts, conferred over a lifetime, as with John Henry Newman, or spontaneously bestowed, as upon Catherine of Siena.

When intellectualism and loyalty are open to each other, all understanding is enlarged. The first without the second breeds cynicism, and the second without the first tempts it. And both breed complacency and self-satisfaction and close us off from the mystery.

Sometimes, the commingling of faith and reason is a neat and natty thing. More often it is a bit messy. But once our intellects have thrashed a matter to its frayed ends, we realize that we have stumbled into mystery, and then, if we are open, we (very reasonably) throw our hands up to heaven and submit to it, because we know mystery for a good adventure, and we are loyal to it.

It is a loyalty that peers into a mirror, darkly, but is never wholly blind.