Like many a comic-book nerd, I’ve been over-the-moon with the strange, genre-bending roller coaster that has been WandaVision, Marvel’s newest series on the Disney+ platform. The show focuses on some of the minor characters who usually get sidelined by the bigger heroes in Marvel’s blockbuster films, and I have been blown away by how Marvel took time to focus on the very real experience of grief and the enduring power of love.

Marvel Comics has long been known for balancing their fantastical superheroes with relatable human problems. The movies have faithfully explored themes such as Spider-Man / Peter Parker’s reckoning with responsibility, the X-Men’s battle for acceptance and belonging, and the Guardians of the Galaxy’s exploration of family. When it comes to films such as Avengers: Infinity War and Endgame, it’s difficult to give certain characters their due when twenty to thirty superheroes are being showcased on screen. WandaVision slows down the action and gives two characters—the metahuman Wanda Maximoff and her synthezoid husband Vision—their time to shine and to process the universal phenomena of human suffering, the fragile nature of mental health, and the consequences of unprocessed grief.

Wanda Maximoff is a tragic figure in the Marvel films. We learn of the death of her parents during her childhood, which happened as a result of a civil war in her fictional eastern European country of Sokovia. Her twin brother is later killed in battle. In a subsequent film, Wanda causes unnecessary destruction to civilians due to the lack of mastery of her powers, and eventually she loses her beloved Vision, who is killed by the mega-villain Thanos. Wanda hasn’t had much screen time to process her suffering. In WandaVision, arguably the most character-focused venture Marvel has undertaken, she now has that opportunity.

It’s a difficult series to nonchalantly jump into if one hasn’t followed the saga over the last twenty-two feature films, but there are serious nuggets to be gathered for the attuned apologist, as Fr. Steve Grunow and Andrew Petiprin have recently discussed. Without spoiling too much, in each episode, we see Wanda and Vision (somehow alive) living in an idyllic home, which jumps decades to accommodate the fashion, technological changes, and stylistic changes of sitcoms from the 1950s to the present day. We eventually learn that Wanda has unconsciously created, through her superpowers, a safe space to repress her grief and pain. The repression of her grief manifests itself outwardly in the family sitcoms she enjoyed from her youth. At first, she can control the illusion, but as the story develops, outsiders and malevolent forces disrupt her facade. Wanda eventually is forced to face every instance of grief that brought her to the point of losing control of it all.

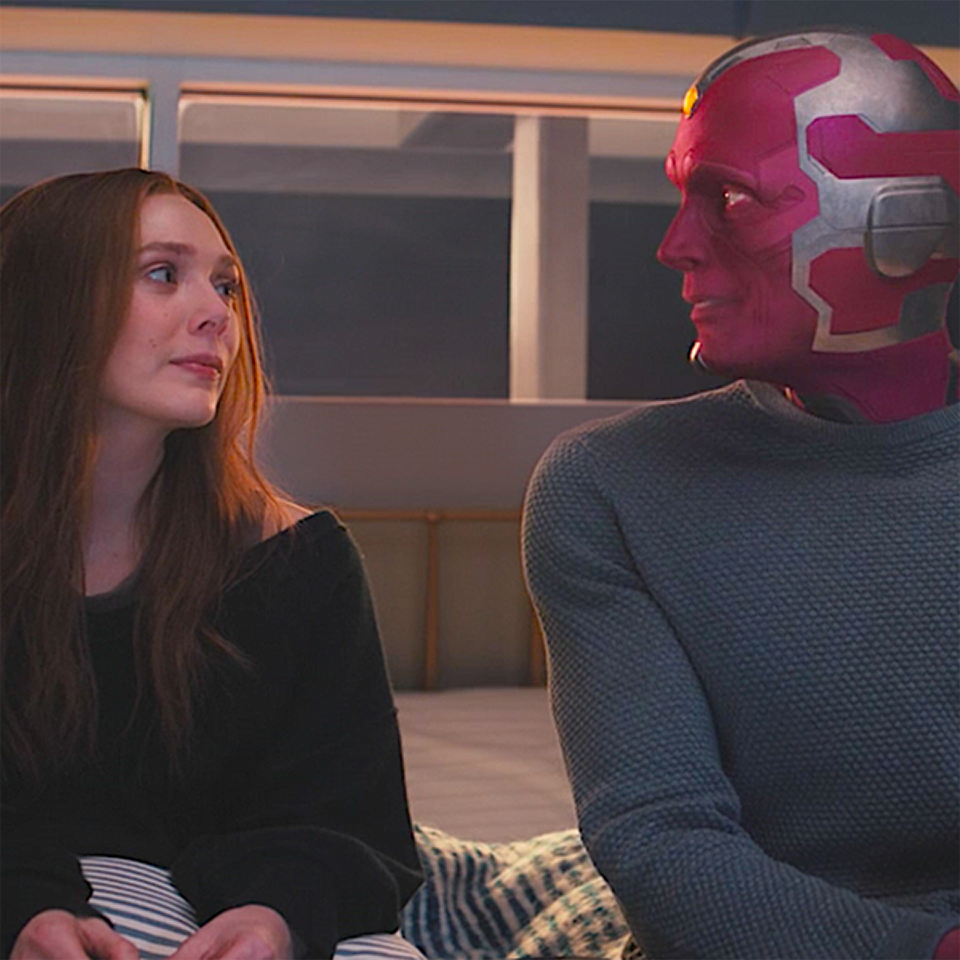

In the eighth episode, we are treated to a number of flashbacks that finally piece the story together. Sitting on a bed, watching sitcoms, and internalizing the safety of nostalgia, she explains to Vision the exhaustion that comes with grief, the feeling of being knocked down by a wave again and again. Vision encourages her to hope, to feel again, to recognize that her love is alive. This quiet moment is arguably the high point of the show.

“But what is grief if not love enduring?” Vision muses to Wanda. It’s one of the most profound lines uttered in Marvel’s entire cinematic run of films, and it made me (and so many others) sit up straight in awe. The naming of grief as something transformative and not something to be repressed or denied struck a chord with anyone watching. This “entering into” sorrow, and experiencing the pain as it is, is something so essential and necessary to human experience—and Christian faith as well.

This reflection calls to mind two great Christian works on the nature of grief and the loss of a loved one: C.S. Lewis’ A Grief Observed and Sheldon Vanauken’s A Severe Mercy. Lewis and Vanauken were friends, interestingly enough, and carried on a correspondence, writing letters of encouragement in the springtime of their marriages as well as in their afterglows. The death of a loved one is an amputation of an emotional, spiritual, and physical kind, and we have medical evidence that stressful losses can be seen in verifiable “broken heart syndromes.” Lewis lays bare his wrestling with God as he processes his agony, but notes that pain is part of the package:

We were promised sufferings. They were part of the program. We were even told, “Blessed are they that mourn,” and I accept it. I’ve got nothing that I hadn’t bargained for. Of course it is different when the thing happens to oneself, not to others, and in reality, not imagination.

Lewis also asserted that grief is a process, not a one-time event. Wanda describes the recurrence of painful memories as waves; Lewis, having served in the First World War, illustrates grief as “a bomber circling round and dropping its bombs.” After losing his own wife, Sheldon Vanauken, a student of Lewis’, faced his grief through writing and composed the magnificent work A Severe Mercy. Vanauken mused, “How could one person, not very big, leave an emptiness that was galaxy-wide? . . . Under the surface of the visible world, there is an echoing hollowness, an aching void—and it cuts one off from the beloved. She is as remote as the stars. But grief is a form of love—the longing for the dear face, the warm hand. It is the remembered reality of the beloved that calls it forth.” I highly recommend both these books for anyone in or out of a season of mourning.

For Catholics, we also walk the way of grief every time we participate in the Stations of the Cross, pray the Seven Sorrows of Mary, or attend the funeral of a loved one. Even the perfect God-man, Jesus Christ, mourned the loss of his friends. Jesus himself wept. Death and sin have disrupted the original plan of God. Every crucifix that hangs on our walls, our necks, or our rearview mirrors likewise ought to be a moment of acknowledging the reality of pain and universality of suffering, but also the triumph of the God, who has taken on our suffering and overcome the pain and separation of death itself.

The Way of the Cross implies movement and our participation in that sorrow to meet the resurrection on the other side. It doesn’t mean that we always understand the grand purpose behind every loss, cancer diagnosis, or painful moment in this life; we are all called to have a maturing abandonment to divine providence. Not repression or denial in our sorrow, but further up and further in, with our friends and support networks to get us through.

By WandaVision’s end, Wanda has essentially progressed through the five stages of grief and is able to release her rage and begin a new chapter of her journey. While Marvel doesn’t perfectly stick the landing to its overall fantastic first streaming series, WandaVision brilliantly illustrates how the experience of grief can testify to a love that is enduring and transformational, a message that resonates deeply with our hope in the resurrected Christ.