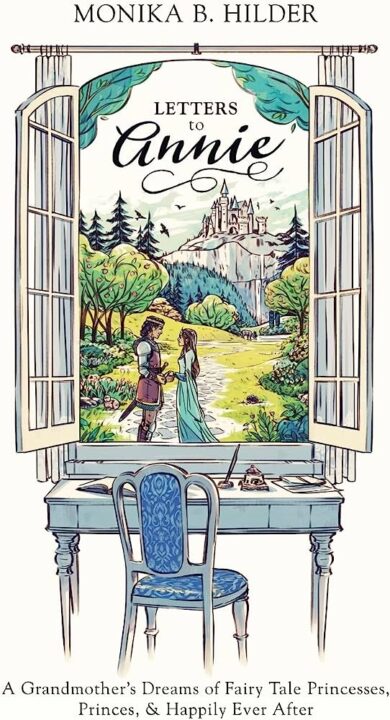

Recently, I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Monika Hilder on the subject of her new book Letters to Annie: A Grandmother’s Dreams of Fairy Tale Princesses, Princes, & Happily Ever After. This is a work of fiction that draws on Hilder’s deep knowledge of literature and culture, both as an academic and as a creative writer, and is very much of interest with regard to imaginative and cultural apologetics.

First, then, a word of introduction: Dr. Hilder is Professor of English at Trinity Western University. In addition to writing fiction, poetry, and drama, she is a scholar of C.S. Lewis and the Inklings and has published on George MacDonald, Madeleine L’Engle, and L.M. Montgomery; her academic work includes a three-volume study of Lewis and gender, beginning with The Feminine Ethos in C.S. Lewisʼs Chronicles of Narnia, in which she makes the case that, far from perpetuating sexism, Lewis offers a biblically inspired challenge to modern Western chauvinism and gender stereotyping. As co-founder and co-director of the Inklings Institute of Canada, she has also co-edited the excellent volume The Inklings and Culture: A Harvest of Scholarship from the Inklings Institute of Canada.

Holly Ordway: For this book, you chose an epistolary format: thirty-three letters written by Omi, the fictional grandmother, to her granddaughter Annie. As you are a Lewis scholar, it’s not surprising that you note the influence of Lewis’s Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer. What was it like as a writer to have Lewis looking over your shoulder, as it were?

Monika Hilder: It was a sheer gift. When I pondered how to write about fairy-tale truths for a wider audience, Lewis’s Letters to Malcolm instantly came to mind. Eureka! In the same heartbeat I knew that I would take the fictional voice of a grandmother writing to her granddaughter. The grandmother would follow Annie for the first twenty-five years of her life, speaking into her joys and sorrows through the lens of fairy tale. This would allow me to draw readers inside Annie’s coming-of-age story as she navigated her (and we, our) various reactions to these stories. My purpose was to celebrate the moral and spiritual truths in these stories that are too easily missed when reading from a Marxist feminist perspective. As for Lewis looking over my shoulder, so to speak, it certainly is challenging, but it’s my habit as I aim for excellence. And I think Lewis might say, “Don’t let me get in the way. You have your own voice.”

Are there other authors or stories that particularly informed your writing of Letters to Annie?

In addition to C.S. Lewis, authors like George MacDonald, G.K. Chesterton, J.R.R. Tolkien, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Vigen Guroian informed my thoughts—all people who have deeply inspired me. But I also looked to authors who wouldn’t see eye-to-eye with me, including Peggy Orenstein and Jack Zipes. It’s always important to listen to everyone, to hear where they’re coming from, as you sort out your own questions and answers. Stories I addressed include “Cinderella,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “The Ugly Duckling,” “Beauty and the Beast,” lesser-known tales like “Jack the Giant-Killer” and “Iron Heinrich,” as well as the Chronicles of Narnia, The Hobbit, and The Princess and the Goblin. The Author Index lists forty-two authors; the Story Index lists fifty-nine stories. And the Biblical Index and the Notes for Further Reading also assist readers.

Regardless of one’s life path and all the curveballs thrown at you, the purity of the soul, redeemed by God’s grace, is key.

In one of the letters, Omi points out how the Cinderella story has “become attached to the beauty myth that a young woman’s physical beauty + romantic love + material wealth = life’s highest goal”—a toxic equation! But you (through Omi) make the case that this is a misreading of the idea of beauty in fairy tales, and you offer an alternate way of understanding it.

We have become a rather shallow, visually fixated, and materialistic culture. So when we think of “beautiful princess” and “handsome prince,” digitally edited images of silver-screen-approved twenty-five-year-olds pop into our heads. I worry a lot about young (and older) people buying into this toxic equation of “physical beauty + romantic love + material wealth = life’s highest goal.” While I have nothing against cosmetics and fine fashion, romantic love that leads to good marriage, and material prosperity, I worry about making idols out of these things—taking secondary things and giving them first place in our lives. This always leads to harm. And let’s remember, plenty of fairy-tale heroines and heroes are single, and the love of money is shown to be evil.

In the book, I tried to raise awareness that beauty in fairy tales is typically symbolic of ethical character. “Virtue is beauty,” as Shakespeare phrased it in Twelfth Night. The good life is based on having a good heart, one informed by truth, hope, and love. While having an ethical character can lead to wedded love and prosperity—imagery of wellness—these are temporal outcomes. It’s the healthy soul that withstands “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.” Regardless of one’s life path and all the curveballs thrown at you, the purity of the soul, redeemed by God’s grace, is key. The book’s theme is “love never fails” (1 Cor. 13:8 NABRE). While romantic love is known as the most fallible of the human loves (see C.S. Lewis, The Four Loves), God’s love sustains us, enables us to flourish. In him alone “we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

Omi, the grandmother, begins the letters when she is sixty-three years old, at Annie’s birth; the final letter takes us to Annie’s twenty-fifth birthday, when Omi is eighty-eight. What was it like to write a book that took you through the aging process of your narrator?

Yes, my awareness of aging and death was significant. In wanting to give readers a long view of the value of fairy tales, as a “grandmother” having tested the stories over the decades, I was conscious that I was writing toward my own death. As an author in my sixties, picturing what it might be like to live into my eighties, I had the privilege of focusing on which things might matter to me and others later, and therefore I could let these insights speak into my life today. So, while I was in a sense writing toward my own death, it really meant that I was living toward my own death with a focus on eternity. What can I say and do today that will matter in the long run? When the sum total of my life is weighed in heaven’s eyes? Whether our lives be long or short, how does God see us? That’s all that finally matters.

Like you, I am a professor, and I have the privilege of mentoring students and writers in my work. It struck me that Letters to Annie is, among other things, a testament to the value of investing time into young people’s lives, a demonstration of love in action, trusting in the work of the Holy Spirit. In your story, it is a grandmother and granddaughter, but it could be godparent/godchild, or teacher/student, or older friend/younger friend. Do you have any advice for people who might have the opportunity to be a mentor, or indeed to a young person who wishes for a mentor?

Thank you. I love what you say about how Letters to Annie struck you. This is certainly my hope for the book. And although I’m not a grandmother, choosing the grandmother voice allowed me to speak with an intimacy that people in other roles might not easily have. Parents can be resisted. Educators might not be confided in. But grandparents who demonstrate care have an easier “in.” Also, I chose the grandmother-granddaughter voices because in our time criticism of fairy tales tends to regard the characterization of females as inferior. Of course, maleness is much criticized today, and I hope that this book equally helps to speak into this problem. (Male and female readers have responded positively to the book.)

And yes, you’re right: the book is intended to inspire anyone who wants to be a mentor. Mentors come in many forms and are badly needed. My advice to anyone who wants to mentor younger people looks like this: pray, be available, listen, acknowledge joy and pain, glean from your own experiences in ways that can nurture the young, believe in God’s wonderful purposes for a young person’s future regardless of what you think you see, and expect the Holy Spirit to lead you. My advice for a young person who wants a mentor looks like this: pray, watch for older people who have proven to be faithful to God and good to others, ask them questions, be open to their advice and ponder it, do not idolize anyone, and guard your heart. Sometimes well-meaning mentors can lead you wrong, but the Holy Spirit always leads you right, so test potential mentors for their character and for the level of wisdom that they offer. As they say, it takes a village to raise a child. And it takes a good community to continue to grow in healthy, life-giving ways.

Readers can find more about Dr. Monika Hilder’s work at her website, MonikaHilder.com.