September 2, 2023 marks fifty years after the death of J.R.R. Tolkien. The UK Royal Mint has even commemorated the anniversary by issuing a special £2 coin featuring Tolkien’s monogram. Around the world, people are gathering to honor Tolkien’s life and works; his imaginative creations are beloved by millions of people of all faiths and none, many of whom have little or no awareness of Tolkien’s own religious identity as a Catholic Christian. We might ask, then, is it even relevant to consider Tolkien’s faith when so many of his readers do not share his beliefs? My answer is a firm “Yes”—and an invitation to all readers, whatever their views, to explore a fascinating and illuminating aspect of the life and indeed the writings of one of the greatest writers of our time.

Tolkien himself observed that “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work.”1 The “of course” is very interesting: of course his epic work is religious and Catholic. It seems natural and obvious to Tolkien that it should be so. The Lord of the Rings, he says, is not superficially religious and Catholic but fundamentally so—at its roots, in its essence. He goes on to say that this religious and Catholic element “is absorbed into the story and symbolism,” woven into the warp and woof of the text, implicit, indirect. It was not “consciously planned”; that is to say, The Lord of the Rings is not an allegory of the Gospels or a tale didactically expressing Christianity. Rather, the whole world of Middle-earth and everything in it is infused with, rooted in, its author’s Christian vision of reality. And he says that this rootedness, this unplanned but essential quality to his work, comes about because he has been raised and nourished in the Catholic faith.

Yet he was also emphatic that his writings could not be read as simple allegories. As he remarked rather tartly, The Lord of the Rings “is not ‘about’ anything but itself. Certainly it has no allegorical intentions, general, particular, or topical, moral, religious, or political.”2

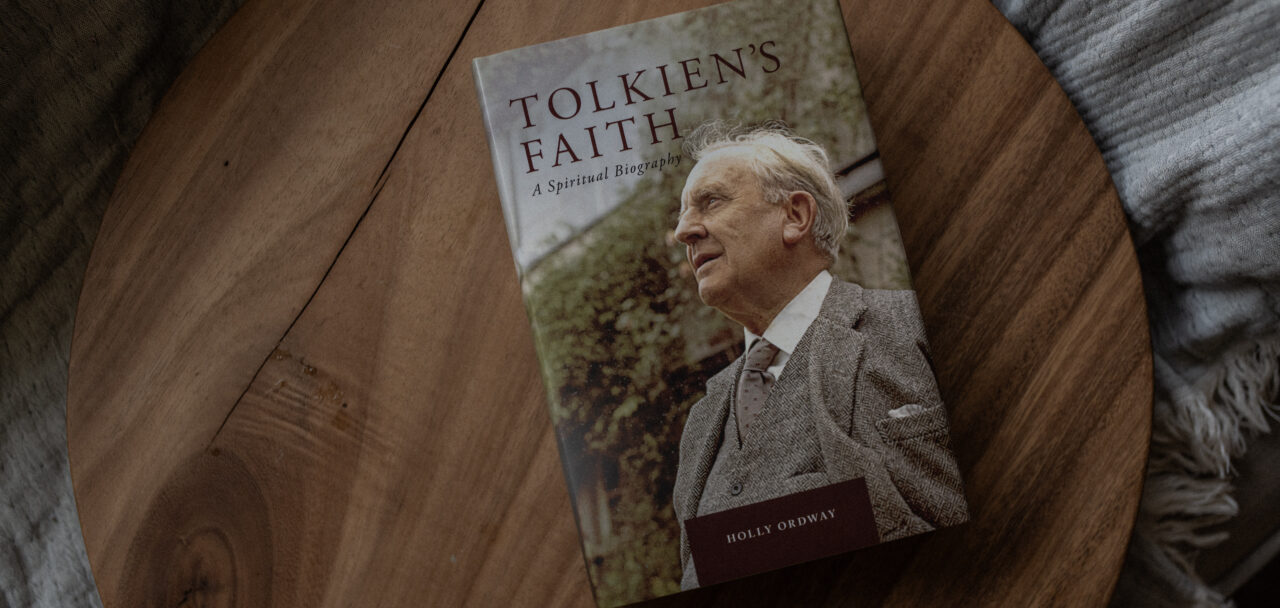

What are we to make of this? How are we to understand the relationship between his faith and his fiction? In my book Tolkien’s Faith: A Spiritual Biography, I have attempted to address that question biographically. In other words, this book focuses on Tolkien’s life—his life of faith—in order to provide context for his works.

Tolkien’s faith was hard-won, and his spiritual biography was one of drama and difficulty.

Until now, there has been no in-depth study of Tolkien’s religious commitments from a biographical point of view. Existing biographies note that he was a devout Catholic, but none explore his spiritual life in any detail. In some cases, this is because it simply isn’t relevant to the focus of the study (as with John Garth’s outstanding Tolkien and the Great War), but in others, his faith has been treated in passing, compartmentalized as a purely private matter, or even basically ignored.

As a result, without even realizing it, we can end up taking Tolkien’s life of faith as a generic, static background to the supposedly more interesting and dynamic aspects of his life. But in fact, Tolkien’s faith was hard-won, and his spiritual biography was one of drama and difficulty.

Although Tolkien was introduced to the Catholic faith by his beloved mother, Mabel, he also had many reasons to relinquish it and return to the Anglican church in which he had been baptized. As a young man, his experience of thwarted love could have embittered him against the Catholic priest who was his guardian. He fought on the front lines of the Great War, a conflagration in which most of his close friends were killed and which caused some of the finest writers of his generation to abandon their Christian faith entirely. In a time when the Church of England’s status as the Establishment religion meant a great deal and Catholics were a socially disadvantaged minority, it would have made his career, his social life, and even his marriage smoother if he had muted his Catholicism or exchanged it for something more conventional. The experience of a second World War, this time with his own sons serving in the armed forces, could have caused him finally to abandon his faith altogether. The turmoil caused by Vatican II, and the loss of the Latin liturgy of the Mass that he loved so much, could have caused him to reject the authority of the Church or withdraw from engagement in Catholic life.

But he did none of these things: his convictions grew stronger and deeper even as he lived through fresh opportunities to set them aside. His process of spiritual growth wasn’t easy. He went through a barren patch as an undergraduate and later a years-long stretch when, by his own account, he “almost ceased to practise” his religion.3 A full treatment of his faith uncovers a life marked by determination and decision.

To understand Tolkien’s faith and what it meant to him, we need to place him fully in context. He was a Christian in an increasingly secular world. More specifically, he was a Catholic in a society that was still, at least residually, Anglican. He lived in a period when significant changes occurred in the way the Catholic Church understood and expressed itself; most of his life came before the Second Vatican Council, but he saw the conciliar years and had views on the changes that the council brought about. Furthermore, he was a Catholic Englishman and therefore part of a faith community that had undergone persecution, marginalization, and restrictions on civil rights, some of which lasted into Tolkien’s adulthood. His perspective was greatly shaped by the close connection he had throughout his life to the Congregation of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri.

By examining Tolkien’s experience of his faith in the time and place and circumstances in which he found himself, we will come to a better understanding of him as a man—and therefore to a deeper appreciation of his writings.

Here I will put my cards on the table. I am, myself, a Christian and a Catholic. I have had the tremendous privilege of spending a great deal of time in England over the last fifteen years and, as a Catholic, regularly worshiping in many of the same places that Tolkien did. At the church of St. Gregory and St. Augustine, Oxford, I have frequently sat in the pew that he usually occupied and have had the privilege of speaking there with his daughter Priscilla, who attended that church herself until her death in 2022. My own faith has been significantly shaped by English Catholicism and indeed by Oratorian spirituality, which has allowed me to gain insights into Tolkien’s experiences that would otherwise have been elusive.

But this book is not an attempt to express my own particular perspective. A degree of subjectivity is inescapable, of course, but I have attempted to portray Tolkien’s faith with its own colors, contours, and emphases as accurately and objectively as I can. I endeavor to serve as a guide, to help the reader see into Tolkien’s experiences as an English Catholic Christian of the twentieth century, grounded in two important locations, Birmingham and Oxford.

Tolkien’s faith was an essential part of his life and how he viewed the world: it shaped what he valued, the choices he made, and how he related with other people. Even if it were for that reason alone, an account of his religious commitments and practices is of interest to readers of his stories, or at least to those readers who want to gain a fuller picture of the man who could create such powerful and memorable works. It mattered to him, and that is a good reason for it to matter to us.

But it also matters if we wish to have a deeper understanding of Tolkien’s creative output. Art will necessarily reflect something of the artist’s most deeply held beliefs, whatever they may be, at least at some level, however subtle or implicit. For Tolkien, faith was not merely a set of opinions but something integral to his real character—and to his own self-understanding as an author. If we are to understand and appreciate Tolkien’s writings to the fullest degree, we need to come to an understanding of what he himself identified as central to his identity: his faith.

Tolkien once described himself as a Hobbit in all but size,4 and in that regard, it is worth recalling Gandalf’s observation in The Fellowship of the Ring that “Hobbits really are amazing creatures . . . You can learn all that there is to know about their ways in a month, and yet after a hundred years they can still surprise you at a pinch.” Half a hundred years after Tolkien’s death, there is still more to learn about him, and more to appreciate and explore in the marvelous literary legacy that he has given to the world. I believe that gaining a firmer grasp of his spiritual identity will enable us to gain a richer, deeper, more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of his writings, and their fundamental but implicit religious dimension.

1 Tolkien, Letters, 172.

2 Letters, 220.

3 Letters, 340.

4 Letters, 288.