Peter Kreeft, esteemed philosophy professor and author of over eighty books, has taught college philosophy for sixty years. Throughout those decades, he yearned for a beginner’s philosophy text that was clear, accessible, enjoyable, and exciting (perhaps even funny). Finding none that met those criteria, he eventually decided to write it himself.

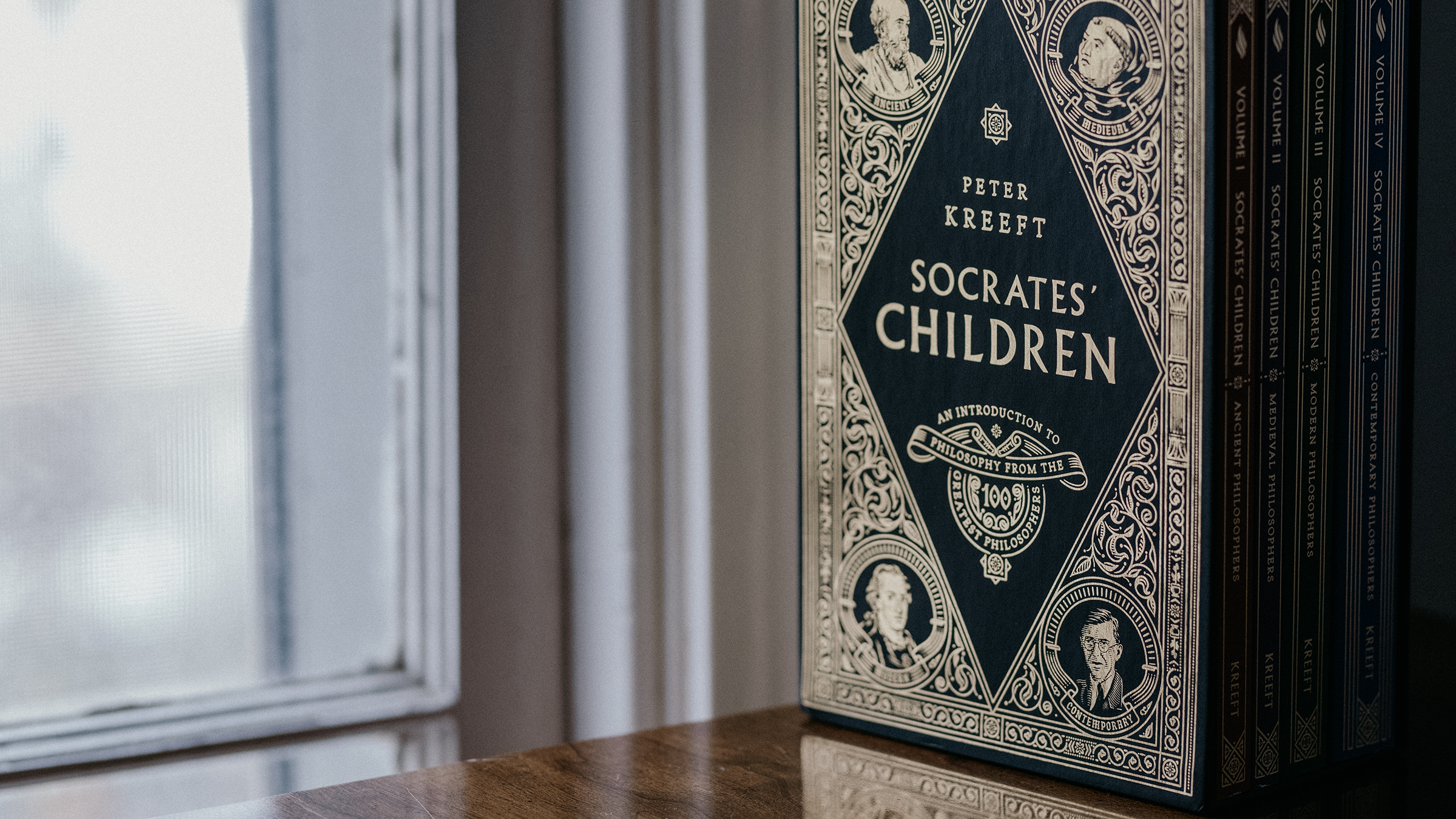

His four-volume series, newly released by Word on Fire, is titled Socrates’ Children: An Introduction to Philosophy from the 100 Greatest Philosophers. With his characteristic wit and clarity, Kreeft examines the big ideas of four major eras—ancient, medieval, modern, and contemporary—and immerses the reader in the “great conversation,” the ongoing dialogue among the great thinkers of history, including the most influential philosopher of all: Socrates, the father of Western philosophy.

Kreeft recently joined us for an interview about philosophy and his new book series.

Brandon Vogt: Philosophy used to be considered a fundamental discipline that all serious people should study. But today, as many schools gut their liberal arts programs, philosophy is rarely required and sometimes not even offered. What’s your case for philosophy? Why should everyone study it?

Peter Kreeft: Wisdom is mentioned over 300 times in the Bible and praised more highly than anything else except love and faith (faithfulness, fidelity, trust). “Without wisdom, the people perish.” “Wisdom is the principal thing; therefore get wisdom.” Philosophy is the love of wisdom. Without the love of wisdom, we do not get wisdom. “Seek and you shall find” implies that if we do not seek (God, and all his attributes, including wisdom), we will not find. Put these two premises together, and you get the conclusion that we very much need philosophy. All need it. Philosophy is far too precious to be left to the philosophers.

The main reason for philosophy’s decline in our universities is that it has largely ceased to be the love of wisdom and has become the cultivation of cleverness and the sophistication of scholarship. There are no magisterially great philosophers today. We cannot name another who we are sure people will still be seriously studying 200 years from now.

You have been teaching philosophy for nearly sixty years at Boston College and have presumably tried many different ways of teaching it. What have you found to be the best approach, and how did that inform your Socrates’ Children series?

I’ve tried all possible and some impossible ways to teach beginning philosophers, and by far the best is Socrates, and Plato’s Socratic dialogues. The classics of philosophy are far more interesting, and even more clear and readable, than anything philosophers write today. Socrates is almost, to philosophers, what Jesus is to Christians: the source and touchstone. I tried to put Socrates into dialogue with other philosophers in my mind (and in some books, where he meets Jesus, Machiavelli, Descartes, Hume, Kant, Marx, Kierkegaard, Freud, and Sartre) and I find that he is like light (his “Socratic method”) that brings out many different colors and shapes (contents) of subsequent philosophers.

Philosophy textbooks have a reputation for being dry and tedious. What makes Socrates’ Children different? How does it compare to other classic texts such as Copleston’s 10-volume History of Philosophy and Durant’s The Story of Philosophy?

Most philosophy textbooks today are “analytic.” They use logical and linguistic analysis on current issues, especially ethical issues, and there is nothing wrong with that. But they are boring. Treating the history of philosophy as a great conversation among the greatest philosophers is much more interesting and dramatic.

Copleston’s ten volumes are a fine research tool but too long and detailed to be interesting to non-philosophy majors. The style is admirably clear but boringly scholarly.

On the other hand, one volume works like Durant’s or Bertrand Russell’s are too short and selective and skewered to one philosophical school.

Socrates’ Children is four volumes long, treats 100 great philosophers, and concentrates on “existentially” important issues that make a difference to our lives. In each case, I show how the apparently abstract and theoretical issues, especially in metaphysics and epistemology, make a crucial difference in the more concrete and practical dimensions like anthropology and ethics.

Your first volume focuses on ancient philosophy and its birth in Greece in the fifth century BC. Why and how did philosophy arise here, among all times and places?

God only knows why ancient Athens became the teacher for the whole world, but the main reason was Socrates. Without him, no Plato, no Aristotle, and no 2,400 years of succeeding philosophy. Every school of ancient philosophy except the Epicurean materialists claimed to be the true disciples of Socrates, as every Christian denomination claims to be the authentic church of Christ.

Philosophy is far too precious to be left to the philosophers.

The second volume turns to medieval philosophy, spotlighting Augustine and Aquinas, two undisputed giants and the two greatest Christian philosophers of all time. What was special about their way of doing philosophy?

Augustine and Aquinas were not only the two most profound and brilliant thinkers in history but also two of the greatest saints. They married deep faith and deep understanding better than anyone else in history. And they stand shortly after the beginning, and shortly before the end, of Christendom, the Christian era, like giant bookends. They were also fanatically honest: no compromises with either reason or faith, logic or sanctity, truth or goodness.

The third volume covers modern philosophy, which you place within the two centuries between Descartes and Hegel (roughly 1637-1831). The major development of this period concerns epistemology. What is that, and why is it important?

Modern philosophy begins anew, with man (Descartes’ “I think, therefore I am”) rather than with God’s “I AM,” and with epistemology (how do we know?) rather than metaphysics (what is real?). It is the “turn to the (human) subject” that corresponds to adolescent self-consciousness: a time of great confusion and trouble but also of great growth and deep question. We are still there, although there is hope (but not assurance) that we will emerge from it into adulthood some day.

Some readers may be surprised by your choice to include G.K. Chesterton as the final philosopher in the series. Why do you consider this jolly English journalist, who never formally studied philosophy, to be one of the greatest hundred philosophers of all time?

My defense for including Chesterton as one of the 100 greatest philosophers is Chesterton himself. He enables you to see things no one else does. He, somewhat like Socrates, turns you upside down and exposes common platitudes with piercing clarity. He is also the philosopher we laugh at the most because he shows us how hilariously insane we are.

What lasting advice would you give someone who is convinced they should study philosophy and ready to begin the pursuit?

Anyone who asked that question has already answered it by actually beginning to philosophize. “Classical” schools do it best by following the advice of the Red Queen to Alice in Alice in Wonderland when she demands Alice tell her story and Alice asks how to do that. The Red Queen answers, “Begin at the beginning. Then proceed to the end. Then stop.” (That’s what life itself does, by the way.) The four years of high school or college are providentially suited to study the four eras of our civilization, and, thus, of ourselves.

Socrates’ Children by Peter Kreeft can be purchased here in the Word on Fire Bookstore.