Every day, it seems more Catholics are waking up to the importance of beauty in the liturgy. Formless sanctuaries and sentimental folk songs were the accepted norm for Church aesthetics just a few decades ago. Now, a growing body of the faithful is calling for a return to tasteful hymns and chant, well-crafted architecture, and statues and images that lift the soul to God.

This is a positive development overall. Ugliness inspires little devotion and turns away potential converts. Moreover, it is inappropriate to the liturgy on its own merits, because worshiping God should invoke the best we have to offer, physically as well as spiritually. Nevertheless, there is a real danger that Catholics who overindulge in aesthetic criticism will limit their ability to give beauty its true due—and to give God his.

Consider the case of a young woman whose taste for beauty is awakened when she first hears Gregorian chant after a lifetime of Marty Haugen hymns. Invigorated by the experience, this woman seeks to understand what makes one more beautiful than the other and begins educating herself in aesthetics. Over time, she becomes more attuned to the virtues and vices of the music she listens to, the buildings she inhabits, and the artworks she sees. This process is both thrilling and fulfilling.

One day, however, the woman’s expertise becomes a burden. She finds herself unable to attend Mass without grumbling at minor aesthetic flaws. She tries to cultivate charitable thoughts, but she grows increasingly nitpicky and judgmental. “Low-quality” services eventually become a near occasion of sin. In the end, the young woman discovers she is more knowledgeable, but less virtuous—the exact opposite of what she aimed for at the start.

Modern society in general favors an excessively analytical “Rationalism” at the expense of the mental “mode” of delight.

This story is obviously a caricature, but it is based on reality. A seminarian recently told me, for instance, that he and his classmates are so prone to excessive aesthetic criticism that they have begun enforcing a rule of silence after attending Mass. In my experience, that tendency—to compulsively pick apart beauty (or the lack thereof) in the liturgy—is not unique to seminarians.

Where do these Catholics go wrong? We have already established that their increased awareness of beauty and desire to see that beauty realized in the Church are a positive development. So, where is the line between good taste as a virtue and “good taste” as a vice? What separates the ability to appreciate art from the disability to stop criticizing art?

The answer lies in the distinction between analysis and what the Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand calls frui. These mental activities are often confused because they both involve heightened attention to external objects. Nevertheless, they have different natures and ends. Analysis is the use of reason to make scientific or practical judgments about objects, keeping said objects at arm’s length. Frui, meanwhile, is the enjoyment of or delight in objects in themselves, in a manner that draws the subject and objects together.

Analysis and frui both have roles to play in the spiritual life, but they cannot be performed simultaneously. Therefore, each activity’s propriety depends on the circumstances. Hildebrand explains in Transformation in Christ that “whenever we are concerned with the elucidation of . . . problems, the rational analysis of the object is fully justified: but . . . should a profound significance and a high value attach to the contents of an object or situation, then we are summoned by these . . . to approach the stage of frui.”

At the risk of oversimplification, this means that while occasions of education, instruction, or practical evaluation often call for analysis, dramatic encounters with goodness, truth, and beauty call for us to set analysis aside, instead simply enjoying or delighting in the value we have been granted access to. Why? Because God made us for relationship with goodness, truth, and beauty more than just knowledge of them.

Catholics go wrong, then, when they analyze objects’ beauty or ugliness when they should be performing frui. For example, Hildebrand imagines a man listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony who, “instead of allowing his soul to absorb the beauty of the music and to give free rein to its delight . . . dissects the object present to his senses and examines the reasons why it is beautiful.” Such a man’s “excessive rationality . . . deprives [him] of genuine surrender to value.”

The philosopher Michael Oakeshott, though not a Christian, develops the same theme in his famous collection of essays Rationalism in Politics. Per Oakeshott, modern society in general favors an excessively analytical “Rationalism” at the expense of the mental “mode” of delight. This is actually “anti-aesthetic,” because, as Professor Elizabeth Corey paraphrases, genuinely appreciating beauty requires “graceful acceptance of what one is given, [while] Rationalism presses always forward in a Pelagian striving for some future state of perfection.”

Allowing analysis to crowd out frui in the context of the liturgy, however, is more than anti-aesthetic—it is anti-religious. The liturgy, after all, is the supremely dramatic encounter with Goodness, Truth, and Beauty. It is a direct meeting with God himself. As such, it deserves to be joyfully participated in, not picked apart.

Hildebrand puts it this way: “We are not only called to know God . . . ; we are called to love Him and immerse ourselves in His love.” This immersion is only possible through “self-surrender and in the abandonment implied in the response to value.” As we have established, excessive analysis prevents those acts.

In short, even as we hone our aesthetic faculties, we must remember why these faculties exist. They exist to help us distinguish good art from bad art, yes. But more importantly, they exist to help us enjoy and ultimately participate in objects of great value—to perform frui. In the context of the liturgy, this means delighting in God himself.

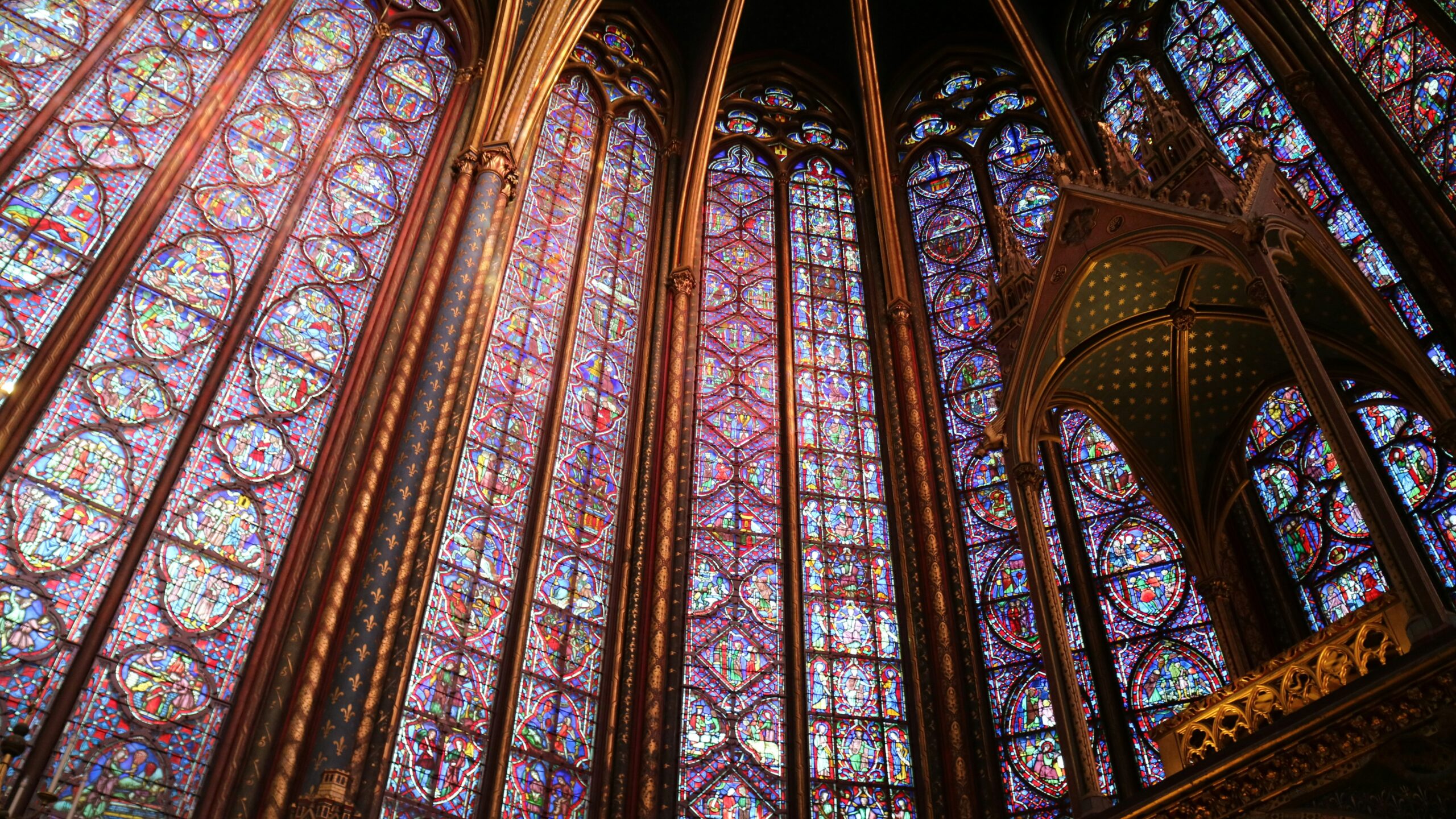

This can be done by immersing ourselves in beautiful music, architecture, and paintings. Or it can be done by, at times, patiently enduring ugly music, architecture, and paintings—and by looking past them to see Christ in Word and Sacrament. But we will never fulfill our liturgical duty if we remain intellectual spectators and compulsive critics, regardless of our aesthetic circumstances.