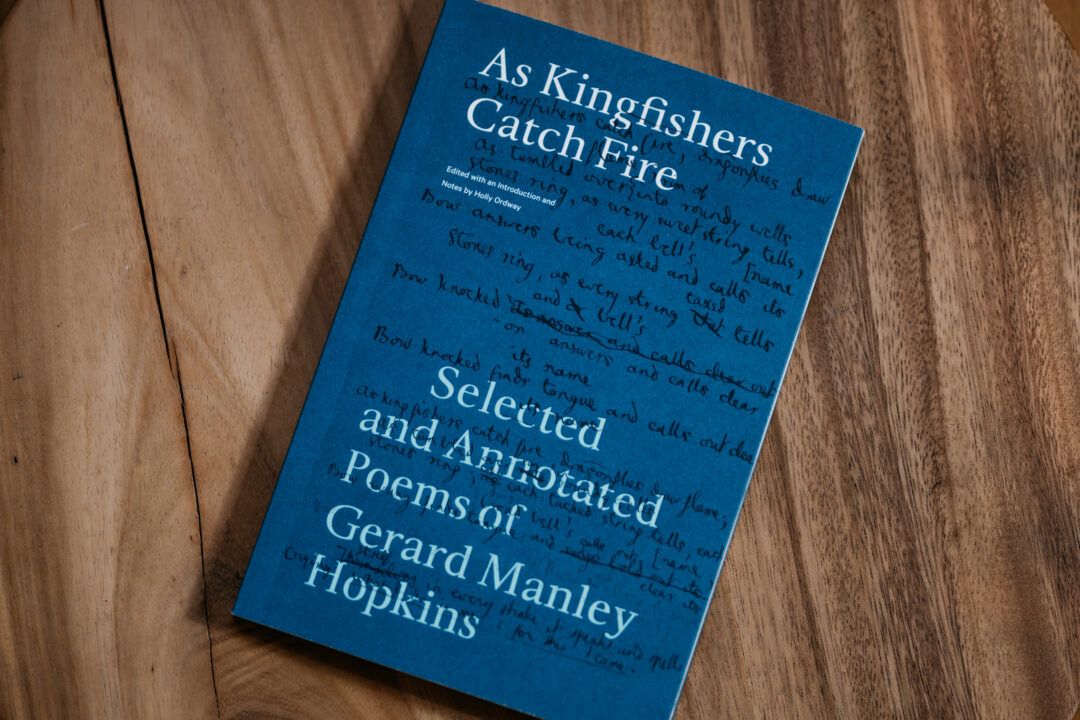

This article is adapted from As Kingfishers Catch Fire: Selected and Annotated Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, edited by Holly Ordway.

I first encountered the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins exactly thirty years ago, in an undergraduate English course, and though at the time I barely understood what I was reading, something about his poems—ones like “The Windhover,” “God’s Grandeur,” and “Carrion Comfort”—resonated with me at a deep level, and he has stuck with me ever since. Along with C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, he had a great deal to do with my eventual conversion to Christianity, and later full reception into the Catholic Church, and I’ve had the pleasure of teaching his poetry to undergraduate and graduate students over the years.

And so I am especially delighted to bring out As Kingfishers Catch Fire: Selected and Annotated Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Selecting the poems for this volume, writing the introduction, and above all, extensively annotating each of the poems included in it has been a great joy. Hopkins’ rich, evocative imagery carries an intensity of meaning that makes his poetry particularly well suited to convey what Bishop Barron has called the “weirdness” of Christianity. To borrow Hopkins’ description in “Pied Beauty” of God’s creation, our faith encompasses “All things counter, original, spare, strange; / Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?).”

The title of this book is taken from Hopkins’ great poem that opens with the line “As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies dráw fláme. . .”, a sonnet that gives a vivid picture of what it means to have one’s identity in Christ.

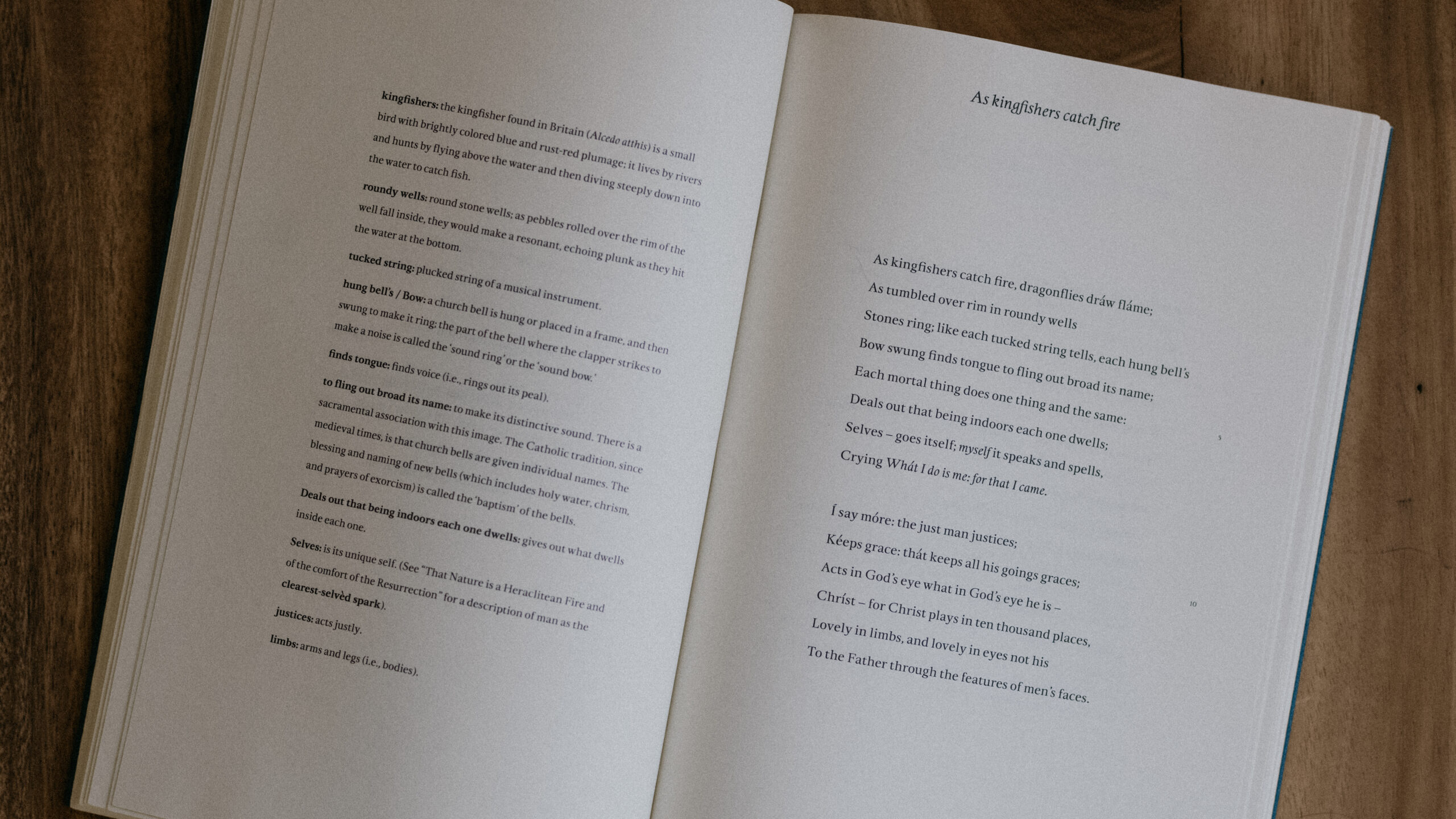

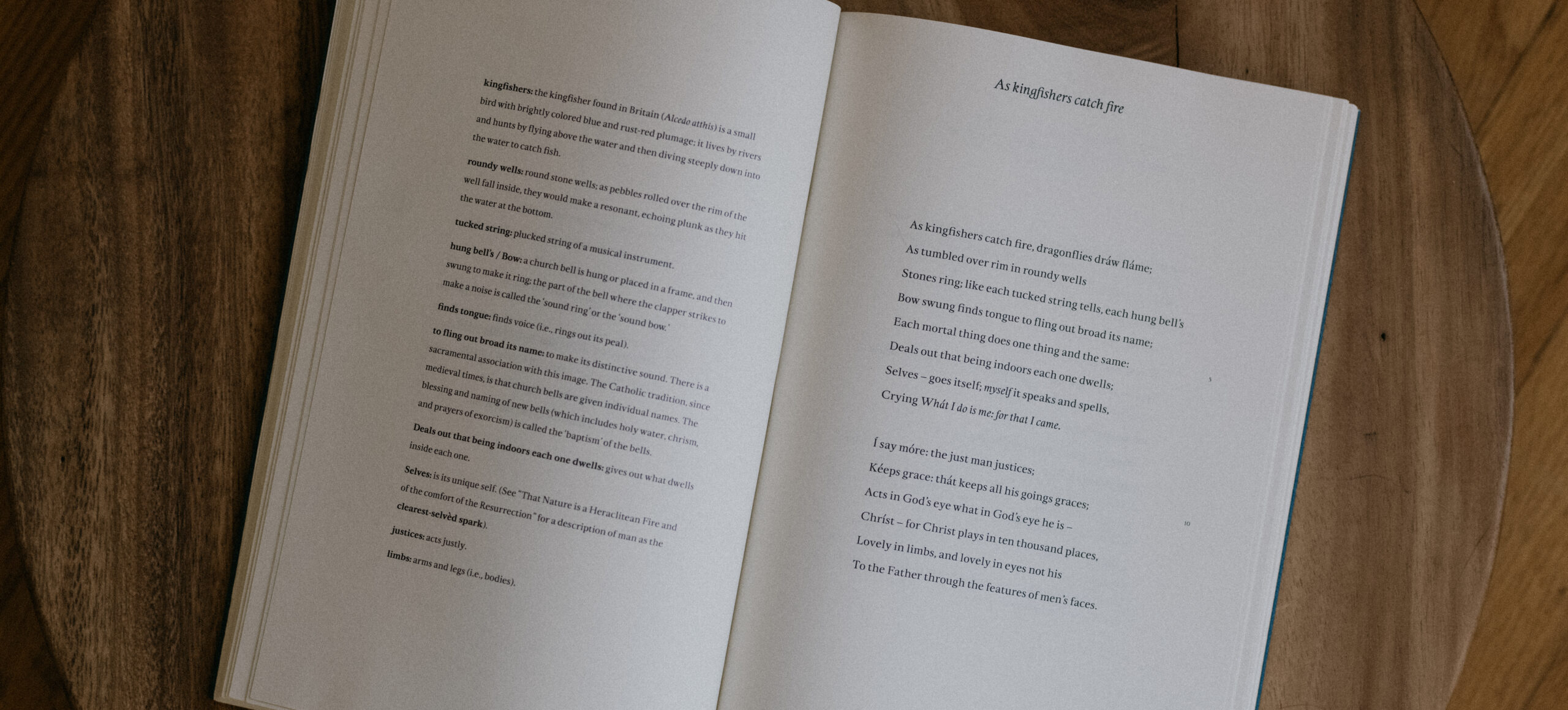

Here is the poem as it appears in the volume, with its facing-page annotations:

“Kingfishers” is a deeply experiential poem. The octet (the first eight lines) and the sestet (the next six lines) flow from beginning to end with pauses but no full stops; like water flowing downhill, we fall from one image to the next in sequence, ending up pausing at the opening phrase of the sestet: “I say more.” Reading the poem aloud (go ahead, do it!) brings out its music.

Not only does the poem sound beautiful, but this music is paired with images of beauty. Kingfishers: brightly colored, fast-moving birds; dragonflies: elegant jewel-toned insects whose name itself echoes fantastic creatures of medieval myth. The created world, made by God through Christ, is faithful in being what it was made to be.

Then the poem moves on to the human interaction with God’s creation: wells, evoking fresh water, but also mystery and magic (think of tossing coins down a wishing well), and a child’s playfulness in tossing a stone into a well just for the pleasure of hearing the ring of the falling stone. The swinging bell flings out the note in joyful exuberance, and here, with the image of the bell calling out its name, Hopkins subtly evokes the sacrament of Baptism.

These lines draw us into an experience of pure, unmediated joy—and then Hopkins tells us what that joy is, starting with the hint given by the bell calling out its name. “Each mortal thing does one thing and the same . . . myself it speaks and spells; / Crying What I do is me.” All things naturally express their own identity—and the poem’s first lines have helped us feel, deep in our bones, that this identity is a joyous one. Hopkins goes a step further: following “what I do is me” we have “for that I came”: he takes us in one beat from identity to purpose.

We feel the joy of the kingfisher, dragonfly, stone, bell, and man each being exactly what they are meant to be . . .

Having introduced the idea of purpose at the pivot-point of the poem, Hopkins says “I say more,” declaring that he will unfold the meaning behind all of this.

However, he does not immediately name Christ; rather, he turns first to the human experience, “the just man justices”; by making a verb out of the noun justice, Hopkins makes the connection of identity and action concrete. This just man “Keeps grace: that keeps all his goings graces”—a play on words that emphasizes that God’s gift of grace is what allows the man to have all that he does unfold in grace. The word “grace” helps the reader make the connection between joyful identity and Christ before Christ is named, so that the evocation of Our Lord will be heard not as an evangelizing add-on, but as the piece that makes all the rest fit together perfectly.

For Hopkins points to Christ at the heart of everything. The just man “Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is— / Christ.” Here we have a poetic restatement of St. Paul’s words: “it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal. 2:20). Hopkins closes the poem with words that express the joy of living out that identity: “for Christ plays in ten thousand places, / Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his / To the father through the features of men’s faces.”

The fact that “Kingfishers” is beautiful purely as a poem draws us deeply into the heart of this experience: as poet, Hopkins takes us through a lived moment of pure, joyful Christian identity. We feel the joy of the kingfisher, dragonfly, stone, bell, and man each being exactly what they are meant to be: rooted, grounded, graced in Christ.

Get your own copy of As Kingfishers Catch Fire: Selected and Annotated Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins today in the Word on Fire Bookstore.