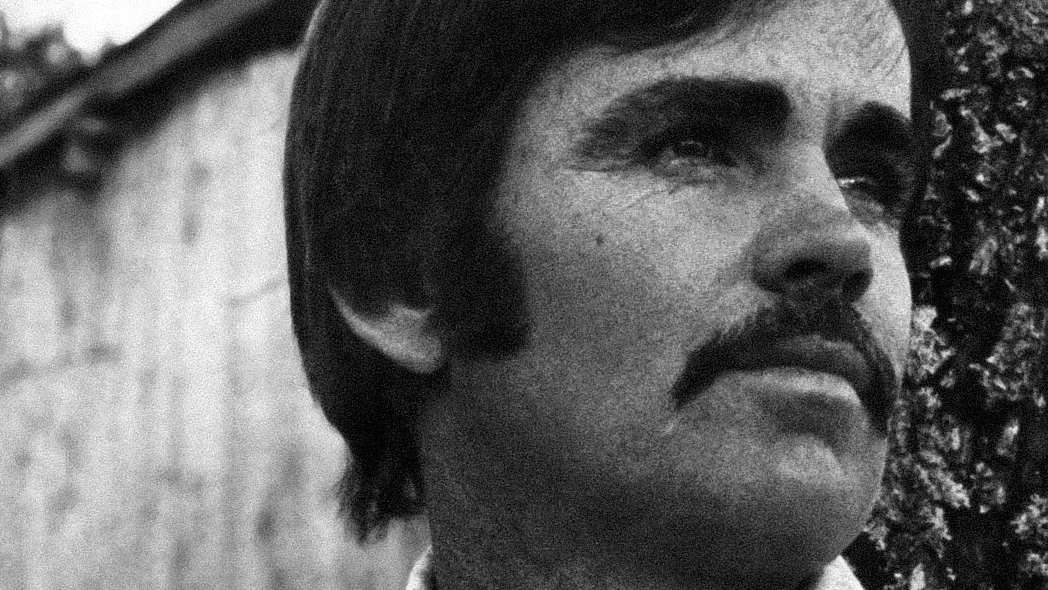

The most arresting author in modern American fiction, Cormac McCarthy, has died at the age of 89. A writer who even during his lifetime was compared to Herman Melville, William Faulkner, and Flannery O’Connor has left an incomparable literary legacy. His enduring stories and many immortal characters—Lester Ballard, Cornelius Suttree, Judge Holden, John Grady Cole, Billy Parham, Llewelyn Moss, Anton Chigurh, the unnamed father and son in The Road—will occupy the American imagination until perhaps the eschaton.

McCarthy is, in my humble and insignificant view, in contention for the title of most important American fiction writer of the 20th century, for the simple reason that his narrative mind was married to his insight into the essence of things. Robert Penn Warren wrote that McCarthy’s stories have “the stab of actuality”: his insights are undeniable, his questions irresistible, his characters as incarnate and tangible as your next door neighbor. He gets in your face, and you can’t look away. His potent literary realism accompanies a refined philosophical understanding of his own time.

Like Nietzsche, McCarthy believed that human society has rejected a transcendental order that moves and rules all things. Also like Nietzsche, McCarthy believed that human society needs a transcendental order and is moved by an endless desire for it. His fiction, consequently, is post-Nietzschean, one may even say post-apocalyptic, in the sense that all of his stories are situated in a world whose foundation is not ipsum esse subsistens (the sheer act of being itself) but rather the death of such, and all that remains is an immanent, material cosmos that is immensely beautiful and soul-stirring yet merciless and indifferent. His characters are preoccupied with this dilemma: the yearning for a supernatural logos that is constantly besieged by everything that obscures what could be its presence. Even the explicit religious figures in McCarthy’s books are subscribed to this disposition. The priests and preachers who are not intentionally characterized as fideistic and naïve, and most of them aren’t, presume an absence of divine design and an animating principle of chaos.

His potent literary realism accompanies a refined philosophical understanding of his own time.

To put it another way, McCarthy invented a world that mirrors our own post-Nietzschean culture. Born with the natural human instinct for seeking transcendence, we inherit a social imaginary, to use Charles Taylor’s phrase, that rejects outright the notion of a Creator and subsequently sees and searches for nothing but immanence. The world and the human person may be beautiful and captivating, but ultimately they have no telos, no final end. We are powerless before this rendering of reality because in effect, we take it with our mothers’ milk.

And this is what makes McCarthy utterly vital. He seamlessly apprehended the contemporary human problem through timeless fiction, and with intense clarity showed that we can’t ignore that problem. The post-Nietzschean social imaginary guides our life, and we are helpless to avoid that. But his sobering insight is also a penetrating exhortation: don’t run away from it. Engage it. Face it head on. Tackle it. Wrestle it like Jacob wrestled the angel at the Jabbok.

All of McCarthy’s work strives with this paradox, and though his conclusions never repudiate the Nietzschean cosmos (McCarthy himself abandoned the Catholicism of his childhood and never returned), he has left behind a robust model for never giving up in the search for a resolution to it. He exudes the masculine, indefatigable virtue of fortitude with a postmodern consciousness. The tried-and-true modes of arriving at the uncaused cause and finding repose in a divine mind no longer hold sway, and he did not propose a concrete path forward. But he never stopped walking.

McCarthy’s play The Sunset Limited comprises a conversation between a Christian ex-convict and an atheist professor after the ex-convict has saved the professor from committing suicide. The professor is just as desperate to die as the ex-convict is desperate to evangelize him. The entire conversation is a clash between the philosophical bedrock of the current social imaginary against the basic, indispensable human impulse to seek and know God, what Luigi Giussani called the religious sense. At times, this clash is as brutal as any violent scene of carnage that appears in a McCarthy novel, and in the end, the professor remains steadfast in his intent to kill himself. After he leaves the ex-convict’s apartment to jump in front of a train, the devastating last lines of the play are left to the ex-convict, alone and inconsolable and with nothing left but a helpless prayer:

He didnt mean them words. You know he didnt. You know he didnt. I dont understand what you sent me down there for. I dont understand it. If you wanted me to help him how come you didnt give me the words? You give em to him. What about me? . . . That’s all right. That’s all right. If you never speak again you know I’ll keep your word. You know I will. You know I’m good for it. . . . Is that okay? Is that okay?

McCarthy gives these two irreconcilable attitudes toward reality equal weight, the behemoth of nihilism in tandem with a quiet openness to a structure beyond human experience. The key to this in McCarthy’s mind seems to be death, the only sure fate and thus the criterion through which to evaluate anything. As he said in one interview, “Death is the major issue in the world. For you, for me, for all of us. It just is. To not be able to talk about it is very odd.”

Though one cannot be certain he viewed death as salvific, it is plausible that McCarthy was amenable to the idea that any possible resolution to the human problem would have to involve death. And this is perhaps the one instance where his religion never left him. His literature forever hangs in the balance.

All that might be left to say is to let Cormac McCarthy speak for himself. There is a scene in The Road where the father is dying and speaks to his son for the last time. It proceeds as follows:

I want to be with you.

You cant.

Please.

You cant. You have to carry the fire.

I dont know how to.

Yes you do.

Is it real? The fire?

Yes it is.

Where is it? I dont know where it is.

Yes you do. It’s inside you. It was always there. I can see it.

Cormac McCarthy, requiescat in pace.