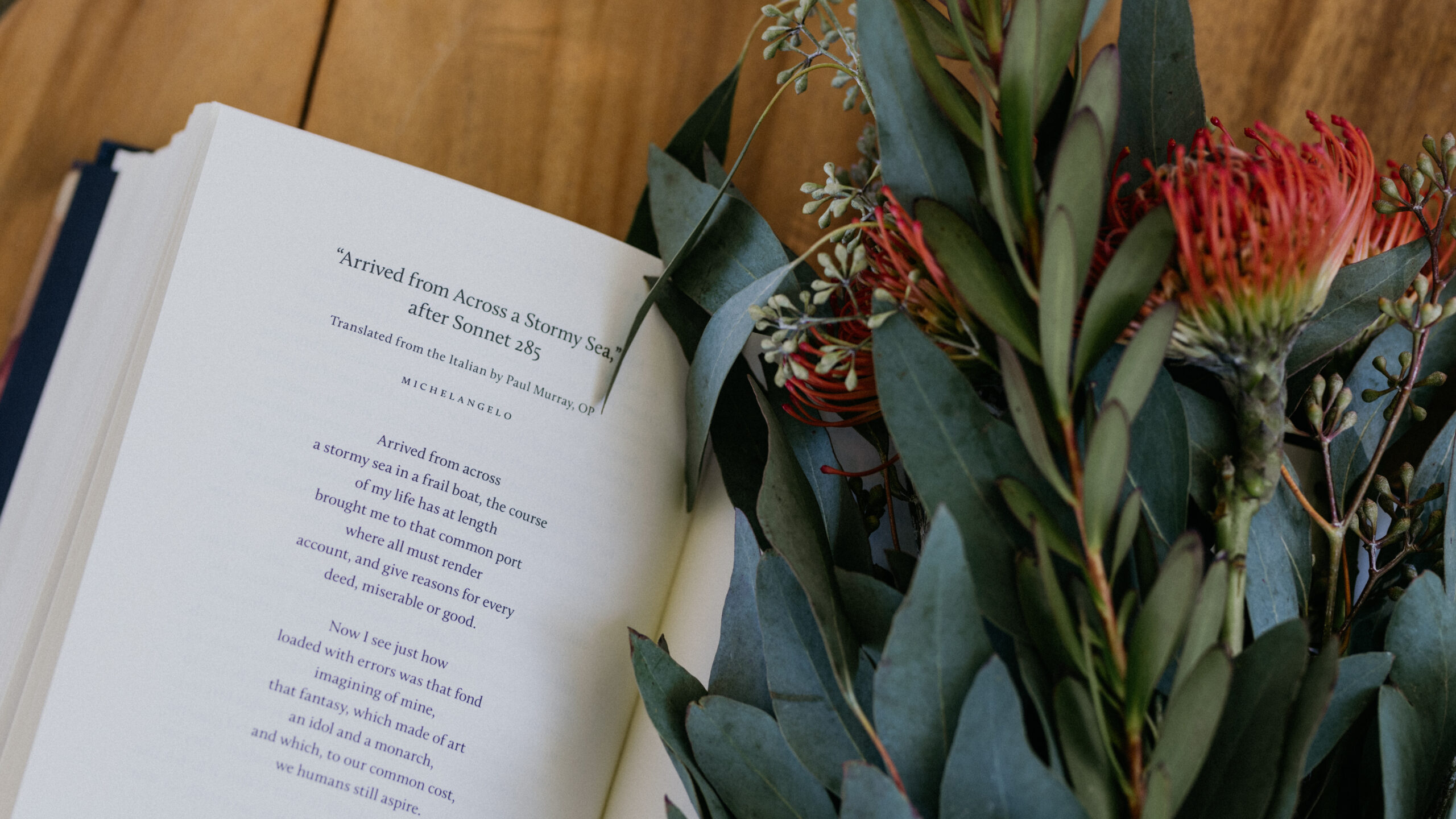

Here is an excerpt from a poem. Take a moment to read through it, slowly, out loud if possible. Enter into each line, not merely what it says but how it sounds. Create the space in your heart not simply to figure out what it means but more importantly, to experience the poem, delight in it, savor it.

And he of the swollen purple throat,

And the stark and staring eyes,

Waits for the holy hands that took

The Thief to Paradise;

And a broken and a contrite heart

The Lord will not despise.The man in red who reads the Law

Gave him three weeks of life,

Three little weeks in which to heal

His soul of his soul’s strife,

And cleanse from every blot of blood

The hand that held the knife.And with tears of blood he cleansed the hand,

from Oscar Wilde’s “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”

The hand that held the steel:

For only blood can wipe out blood,

And only tears can heal:

And the crimson stain that was of Cain

Became Christ’s snow-white seal.

Sally Read declares, in the brand-new anthology 100 Great Catholic Poems, that “poetry is the language of Catholicism.” If we take this statement at its word, then the implication is startling: Catholicism is incomprehensible without poetry. If one’s Catholic life lacks poetry, then one’s Catholic life is incomplete.

Of course, such a statement sounds preposterous. Why would such a thing as poetry be so crucial to the Church? And if it is so crucial, why is it so seemingly absent in the Church, so lacking in the preaching of priests, the Catechism, the Church’s precepts, and all of the other major aspects of the Mystical Body of Christ?

Devout poets and scholars like Dana Gioia and James Matthew Wilson have written scores of defenses regarding this. Besides my own shallow foray into the conversation here, I exhort readers to delve into the meat of this problem as much as possible, particularly with Read’s introduction in 100 Great Catholic Poems (alongside fundamental tracts found here, here, here, here, and here).

Poetry is a universal form of engagement, however excellent or poor, with the depths of our being.

For my own humble part, it appears that there are at least two dimensions to the problem: the lesser one concerns a rather simple misunderstanding, and the greater one concerns a corrupted vision of the real. The rather simple misunderstanding is that poetry is not, as most believe, just one leisure activity among many that a person might choose in his spare time if it happens to be of interest to him. Rather, poetry is a universal form of engagement, however excellent or poor, with the depths of our being. As Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren remark in their indispensable book Understanding Poetry, “Poetry is not an isolated and eccentric thing, but springs from the most fundamental interests which human beings have.” Every human person, conscious of it or not, uses the poetic form to reckon with his or her own existence.

Much more than mere words on a page expressing lofty feelings or emotions, poetry is the act of giving voice to the otherwise incommunicable facets of life. The most concrete example of this is when spouses say to one another, “I love you.” That statement is essentially poetic because it captures the very nature of one person’s relationship to the other. Such a relationship simply cannot be captured in precise, scientific, clinical language because its nature transcends material experience and is in fact grounded in the One from whom we receive our being and our ability to love in the first place (1 John 4:16). A moment’s meditation will suffice to realize that communicating the incommunicable is far more common than we think.

When the fog is cleared and we get at the true definition of poetry, we find its presence everywhere in Catholicism: the Scriptures, the Mass, the prayers of mystics and monks, and the very nature of God. God himself is a poet. In the first verses of Genesis, by an act of speech, God brings about reality from nothing. To paraphrase the classic formulation, God’s engagement with the depths of his own being in the Trinity overflows into the creation of the world. All that is out of reach, unfathomable, impossible, is grasped by the Word who was there at the beginning. This is hardly hyperbole because God made man in his own image and bestowed him with the same power in a lesser degree, as evidenced in his naming of the animals. In fact, by virtue of his own created nature, the human person is a poem all his own; his existence is a particular expression of a concrete but mysterious act of God that takes form in his individual vocation. This reveals why all people, especially Catholics, need poetry and lack something essential without it, because their vision of reality is ipso facto hindered by not enunciating what occurs at the ground of our being. We become, as T.S. Eliot said, “hollow men.”

Poetry as a specific art form has thus accompanied the human experience from its very origin. Both creating and enjoying poetry have comprised major roles in all cultures up and down the ages and, until recent times, were wholly accepted as essential to living a full life because human existence is lived mystery and poetry teaches us to live that mystery.

This leads to the greater dimension of the current dilemma. The human capacity for poetry, due to the various philosophical, historical, and spiritual circumstances that have conditioned the contemporary vision of life, has simply been shattered. When once it might have been taken for granted that the riddles of God were more satisfying than the solutions of man (to borrow Chesterton’s phrase), the mere idea that human life should be characterized by mystery is shunned and avoided like the plague. Even the idea of reckoning with the depths of our being is repulsive or, at the most, pondered at the surface level. Language should be nothing but practical and the meaning of words should be only literal. All that is real is just material. Whatever might be incommunicable and unfathomable, even the nature of love, has been made subject to the individual’s judgment of his worth in his own personal life. In short, the contemporary vision of life is toxic to poetry, to the point that its base emotional satisfaction or motivation to political activism constitutes its worth.

And one would be deeply deceived to believe that Catholics are protected from this vision. The Liturgy of the Word in Mass is treated merely like a didactic exercise rather than a sacramental encounter with the Word through whom we were made in the first place. When the priest utters the sacred words “This is My Body . . . This is My Blood” and elevates the Host and Chalice, the all-too-common attitude is to treat it all as a symbolic gesture instead of as Christ the Poet breaking reality open through his “once and for all” act on the cross and initiating the “new creation” lauded by St. Paul and taking form in Eucharistic life (2 Cor. 5:17). Why would the Real Presence of him who is incomprehensible matter at all to someone who has been formed to pine for nothing but a completely comprehensible existence and cannot even tolerate the possibility of the incomprehensible?

The degree to which one engages in prayer coincides with one’s capacity for poetry.

Again, far more complete and refined treatments of this can be found readily, but anyone who has encountered even a smattering of the Gospel can discover the truly mysterious wonder of life, and the fact that our shared perception is toxic to poetry does not make poetry any less vital, as there are some ways forward. Prayer, the very lifeblood of the spiritual life and itself a constant exercise in lived mystery, will always be possible for the human soul, and the degree to which one engages in prayer coincides with one’s capacity for poetry.

Word on Fire has devoted itself to proclaiming Christ in the culture, and poetry is crucial to the effort. To that end, the publishing house has commenced an odyssey into publishing the works of poets old and new (see here and here). 100 Great Catholic Poems is the latest installment, and Sally Read’s powerful work in collecting the best of the Catholic tradition of poetry is second to none. In short, every Catholic should own it.

These currents run parallel to the Catholic literary revival, ongoing for the last two decades, that has been reestablishing the prominence of the literary arts in both the Catholic and public scenes. Publishers and journals pushing the revival forward abound—Wiseblood Books, Angelico Press, Colosseum Books, Cluny Media, The Lamp, Dappled Things, Joie de Vivre, Presence, St. Austin Review—including our very own Word on Fire Publishing and Evangelization & Culture, the journal of the Word on Fire Institute. Make the most of these resources and support them because they fill hollow elements in the life of the Church. Alongside the literary revival is a revival in education, sparked by returning to the sources of classical pedagogy. This pedagogy prioritizes poetic formation and has proved itself to make Catholicism alive in the hearts of children, and Catholics would do well to promote it.

The objective lies not so much in reclaiming something lost but rather dusting off something that has been sitting on the shelf for far too long. In the words of John Senior, consider this to be an invitation to an “experiment in merriment,” the kind of merriment characteristic of authentic Catholicism, the kind that one just cannot have except through poetry.