Here dies another day

During which I have had eyes, ears, hands

And the great world round me;

And with tomorrow begins another.

Why am I allowed two?

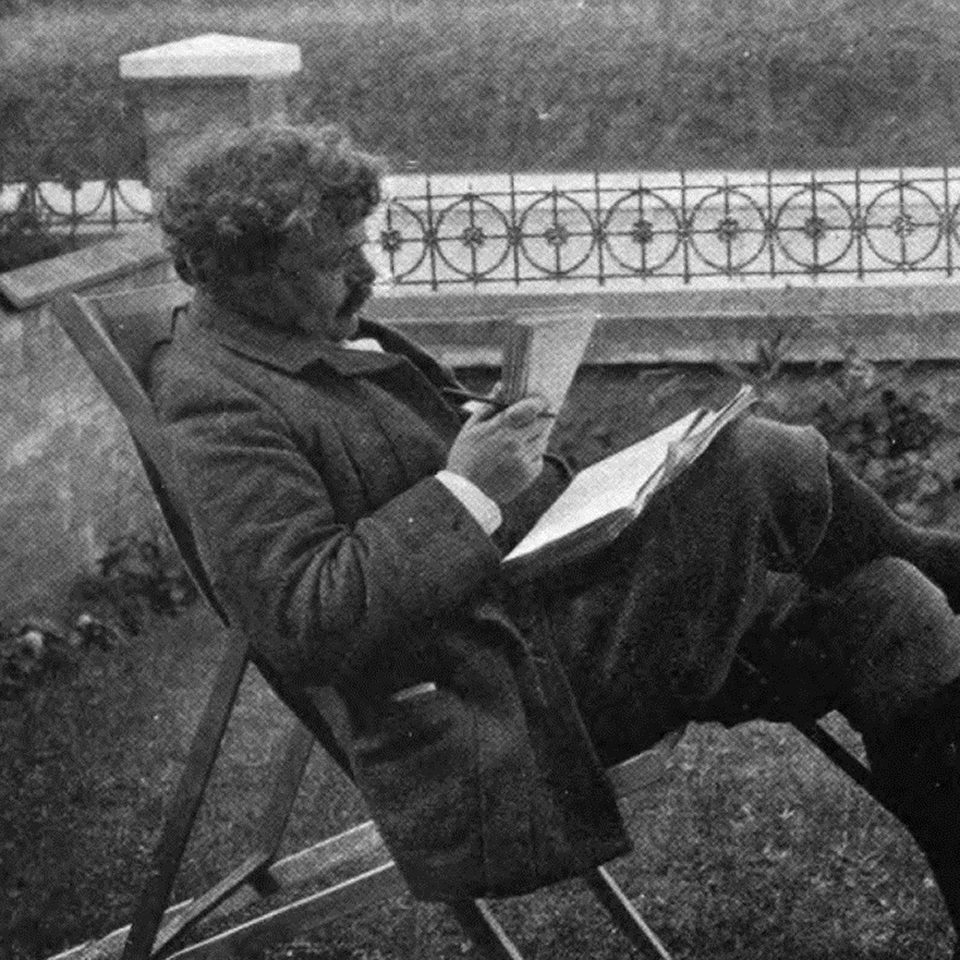

—G.K. Chesterton, “Evening”

Known for his mental acuity and piercing insight, G.K. Chesterton was perhaps at his finest in his most incisive observations. Though Chesterton had the capacity to wax eloquent on everything from the lives of the saints to the form and movement of the cosmos, some of his most memorable expressions, like the one posed in the poem above, are those which seem, on first glance, to be most fleeting. In this pensive fragment of poesy, Chesterton meditates briefly on the state of his own creatureliness; and yet, what seems to be a wisp of an idea expands outward, like the toll of a bell that grows in resonance the longer it rings. Through a genuine and unadorned description of his own experience, Chesterton invites us to adopt his posture to the world, to contemplate, for a moment, two related propositions: first, what it means that we receive the world sensorially; and second, what that revelation might evoke in us as a response.

Chesterton begins by rooting the reader firmly in the world itself. He does this by establishing a set time and day, and then examining his own physical experience of a given space—“the great world round me”—within the confines of that time. Sandwiched between that space and that time, Chesterton places himself, pointing the reader’s attention to the very fact that his body, like ours, is made for sensing: “eyes, ears, hands.” Certainly, this is a fact which most of us take for granted most days; and yet, when it is consciously regarded, it discloses a deeper truth. To be the bearers of sense faculties, to be able to receive and to respond to physical reality, testifies that before we have earned or can claim anything in our lives, before we have established our own identity, before we have acted in any way, for good or ill, before we even are able to consciously perceive the world and ourselves in it, we are born into a reality that is itself fundamentally given, and we are recipients of that givenness. Before we set our senses to act upon the world, the world, and God through it, has already always been acting upon us.

Terrence Malick, in his film Tree of Life, uniquely affirms this givenness. Early on in the film, the story’s central character, Jack, poses a question, seemingly directed from his mind to God’s: “When did you first touch my heart?” In answer, the viewer is thrust into a sequence that begins with Jack’s mother and father as they fall in love with each other, and ends with Jack’s birth. While these bookends are straightforward enough, in between them, the viewer is presented a series of mysterious, impressionistic images: angelic women guiding children by torchlight along a river, or up a set of stairs; a single child swimming upward through a submerged room toward light just past the surface above. Eventually, the viewer begins to understand that in the midst of the chronological sequence of Jack’s gestation and eventual birth, there is another sequence, a sacramental narrative, in which Jack, even while in his mother’s womb, is already set into relationship with a divine grace, as represented by the semiotic imagery. Accompanying this symbolism on-screen is an underscore excerpted from the third suite of Respighi’s Ancient Airs and Dances. “When did you touch my heart?” Jack asks. The image and the music reveal the truth to us effectively: even as Jack is being “knit together in [his] mother’s womb,” as Psalm 139 says, the timeless dance of God’s love has already become manifest somatically through the water and light of that protective, nourishing womb. From the moment we are conceived, we are already receiving the graces of existence itself: cellular regeneration, the development of nerve endings and receptor cells, breath, consciousness. Before anything else about us is true, before anything we understand, conclude, or decide, this ancient symbiosis—of the world as given and us as receivers—is true.

This is the fundamental truth about reality toward which Chesterton seeks to direct our attention. If the world is, in essence, always and constantly given to us, then to have ears and eyes and hands, and to be placed within that “great world round me,” becomes more than an interesting fact about reality. It becomes an invitation, even a call, to participation. Chesterton’s demeanor as an observer in the first line of the poem transitions to one of active participant in the last line: “Here dies another day. . . . Why am I allowed two?” Given what precedes it, that final question is more than simply rhetorical; it is a self-examination, a conscious recognition that what has been so plentifully bestowed in the most rudimentary and visceral aspects of existence in any ordinary day is already such a profound glory that it radically obliterates the possibility of remaining neutral in response to such a sign. The gift of existence, made constantly apparent through our senses, presses us to see the world as a rich summons that merits, even demands, a meaningful answer.

Chesterton’s pattern of observation and response can be easily recognized in Scripture itself. Psalm 19, the timeless exaltation of God’s creative hand at work in the world, begins with a firm declaration of the beauty and majesty that creation intrinsically communicates: “The heavens are telling the glory of God; / and the firmament proclaims his handiwork.” All of creation speaks, says the Psalmist, even without words; thus, creation is itself a sort of word. When the Psalmist suddenly seems to change topic in verse 7, saying, “The law of the Lord is perfect / reviving the soul,” the discerning reader will perhaps recognize a tacit thread between the “word” creation speaks in witness to God and the “precepts of the Lord.” The knowledge that God communicates through creation is intricately interconnected with the law that speaks to us of God’s character. Thus, it is no surprise that a Psalm that begins with “the heavens are telling the glory of God” ends with this line: “Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart / be acceptable to you, / O Lord, my rock and my redeemer.” Creation’s “word” discloses something of who God is; and that revelation calls the observer out of complacency and into worshipful response.

This is precisely the development of thought that Chesterton, through his unassuming observations, seeks to instill in the reader. Just as the glorious world around us is already always working upon us in various ways—through signs in the heavens, through water and light, through every particle of creation, reaching out to our ears and eyes and hands—that revelation compels us to make something of that reality. To receive the world as gift is to recognize a divine act woven into the fabric of all physical reality, an act that merits a reply. Not only can we not consign our senses to some secondary aspect in our journey of sanctification; rather, our senses are a prime means through which we move toward holiness, and toward participation in God’s life.

As we enter into a new year, may we, like Chesterton, ask for what reason our remaining days have been given us, that we might set our senses toward that good and sacred pursuit of making our souls—and bodies—a reasonable, holy, and living sacrifice of praise to the God who seeks us in everything around us.

Joel Clarkson’s new book, Sensing God:Experiencing the Divine in Nature, Food, Music, and Beauty has just been published.