One of the most theologically fascinating and just plain entertaining books I’ve read in a long time is Yves Congar’s My Journal of the Council. Catholics of a certain age will recognize the name, but I’m afraid that most Catholics under the age of fifty might be entirely unaware of the massive contribution made by Congar, a Dominican priest and certainly one of the three or four most important Catholic theologians of the twentieth century. After a tumultuous intellectual career, during which he was, by turns, lionized, vilified, exiled and silenced, Congar found himself, at the age of 58, a peritus, or theological expert at the Second Vatican Council. By most accounts, he proved the most influential theologian at that epic gathering, contributing mightily to the documents on the church, on ecumenism, on revelation, and on the church’s relation to the modern world.

During the entire course of the Council, from October 1962 to December 1965, Congar kept a meticulous journal of the proceedings, which includes not only detailed accounts of the interventions by various bishops and Cardinals, but also extremely perceptive, often arch, commentaries on the key personalities and the main theological currents of the Council. Several times as I read through the journal, I laughed out loud at Congar’s pointed assessments of some of the players: “a bore,” “useless,” “talks too much.” But what most comes through is—if I can risk employing an overused and ambiguous phrase—“the spirit of the Council,” by which I mean those seminal ideas and attitudes that found expression in the discussions, debates and texts of Vatican II. Over and again in the pages of Congar’s journal, we hear of a church that should be more evangelical and open to the Word of God, of the dangers of clerical triumphalism, of the universal call to holiness, of a liturgy that awakens the active participation of the faithful, of the need for the church to engage the modern world, etc. Attending meeting after meeting and engaging in endless conversations with bishops and theologians, Congar was indefatigably propagating these ideas, which we now take to be commonplace, and the permanent achievement of Vatican II.

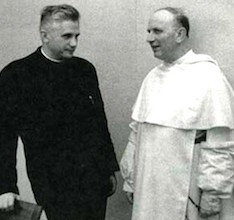

As Congar led this charge, his chief opponents were Archbishop Pericle Felice and Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, the keepers of the traditional, scholastic form of Catholicism. His principal allies were “progressive” council fathers Cardinal Frings of Cologne and Archbishop Wojtyla of Krakow, as well as fellow periti Karl Rahner, Edward Schillebeeckx, Henri de Lubac, Hans Kung, and a young German theologian named Joseph Ratzinger. As I read the pages of Congar’s journal, all of these figures and that very heady time came rather vividly to life. But even as I was caught up in the euphoria of that moment, I couldn’t help but think of the divisions that would later beset that victorious group. Archbishop Wojtyla, of course, later became Pope John Paul II, and he would appoint Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) as his chief doctrinal officer. Further, John Paul would create de Lubac and Congar himself as Cardinals, but would preside over a critical investigation of the works of both Kung and Schillebeeckx. Why did these divisions arise in the post-conciliar period?

One way to get a perspective on the split in the victorious party is to look to the beginnings of the theological journal “Communio.” In the wake of the council, the triumphant progressive party formed an international journal called “Concilium,” the stated purpose of which was to perpetuate the spirit of the great gathering that had prompted such positive change in the Church. On the board of “Concilium” were Rahner, Kung, Schillebeeckx, de Lubac, Congar, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Ratzinger and many others. But after only a few years, three figures—Balthasar, de Lubac, and Ratzinger—decided to break with “Concilium” and found their own journal, and the reasons they gave to justify this decision are extremely illuminating. First, they said, the board of “Concilium” was claiming to act as a secondary magisterium, or official teaching authority, alongside the bishops. Theologians certainly have a key role to play in the understanding and development of doctrine, but they cannot supplant the bishops’ responsibility of holding and teaching the apostolic faith. Secondly, the “Concilium” board wanted to launch Vatican III when the ink on the documents of Vatican II was barely dry. That is to say, they wanted to ride the progressive momentum of Vatican II toward a whole series of reforms—women’s ordination, suspension of priestly celibacy, radical reform of the church’s sexual ethic, etc.—that were by no means justified by the texts of the council. Thirdly, and in my judgment most significantly, Balthasar, Ratzinger, and de Lubac decried the “Concilium” board’s resolve to perpetuate the spirit of the council. Councils, they stated, are sometimes necessary in the life of the Church, but they are also perilous, for they represent moments when the Church throws itself into question and pauses to decide some central issue or controversy. We think readily here of Nicea and Chalcedon, which addressed crucial issues in Christology, or Trent, which wrestled with the challenge of the Reformation. Councils are good and necessary, but the Church also, they contended, turns from them with a certain relief in order to get back to its essential work. The perpetuation of the spirit of the council, they concluded, would be tantamount to a Church in a permanent state of suspense and indecision.

Kung, Schillebeeckx, Rahner, Ratzinger, Congar, de Lubac and Wojtyla were all proud “men of the council.” They strenuously fought for the ideals I mentioned earlier. But in the years that followed, they went separate ways—and thereupon hangs a tale still worth pondering as we approach the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of Vatican II.