Just a few weeks before the most significant Christian holy day of the year, British Prime Minister David Cameron, speaking on an evangelical radio program, articulated what, for him, is the meaning of Easter. He explained that the central message of Easter is “kindness, compassion, hard work, and responsibility.” Now I’m for all of those virtues, but so, I would venture to guess, is any decent person from any background, religious or non-religious. Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, fair-minded agnostics and atheists would all subscribe to that rather abstract and harmless description of the significance Easter. I suppose that, in a sense, we shouldn’t blame the Prime Minister for his anodyne characterization, for the Christian Churches in general, but especially the Anglican Church, have not exactly distinguished themselves for the crispness and energy of their doctrinal formulations. But if that’s all Easter is about, then, not to put too fine a point on it, the jig is up.

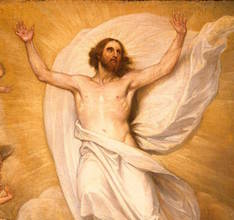

In point of fact, the Easter declaration, properly understood, has always been and still is an explosion, an earthquake, a revolution. For the Easter faith—on clear display from the earliest days of the Christian movement—is that Jesus of Nazareth, a first-century Jew from the northern reaches of the Promised Land, who had been brutally put to death by the Roman authorities, is alive again through the power of the Holy Spirit. And not alive, I hasten to add, in some vague or metaphorical sense. That the resurrection is a literary device or a symbol that Jesus’ cause goes on is a fantasy born in the faculty lounges of Western universities over the past couple of centuries. The still startling claim of the first witnesses is that Jesus rose bodily from death, presenting himself to his disciples to be seen, even handled. It is a contemporary prejudice that ancient people were naïve, easily duped, willing to believe any far-fetched tale, but this is simply not the case. They knew about visions, dreams, hallucinations, and even claims to ghostly hauntings. In fact, on St. Luke’s telling, when the risen Lord appeared to his disciples in the Upper Room, their initial reaction was that they were seeing a specter. But Jesus himself moved quickly to allay such suspicions: “Look at my hands and my feet, that it is I myself. Touch me and see, because a ghost does not have flesh and bones as you can see I have.” While they were still, in Luke’s words, “incredulous for joy,” the risen Jesus asked if there was anything to eat and then consumed baked fish in their presence. This has nothing to do with fantasies, abstractions, or velleities, but rather with resurrection at every level.

Once we’ve come to some clarity about the resurrection claim itself, we can begin to see why it still matters so massively. Let us look at the kerygmatic sermon that St. Peter preached in the Jerusalem Temple in the days immediately following Pentecost. Though it flies in the face of our expectations regarding preaching, there is nothing namby-pamby or ingratiating about what Peter tells the crowds. “The God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob…has glorified his servant Jesus, whom you handed over and denied in Pilate’s presence…You denied the Holy and Righteous One and asked that a murderer be released to you. The author of life you put to death.” The resurrection is being presented here as an affirmation of Jesus to be sure, but also as a judgment on those who stood opposed to Jesus. St. Peter holds it up as the surest sign possible that God stands athwart the injustice, stupidity, and cruelty of the world and its leaders. If the resurrection is only a bland symbol or a projection of our desires, then tyrants have nothing to fear from it. But if it is a fact of history, an act of the living God in space and time, then sinners have real cause to repent. It is absolutely no accident that the most brutal tyrants of the twentieth century moved quickly to eliminate those who would articulate, in no uncertain terms, the good news of the resurrection. And it is, by the same token, no accident that some of the last century’s most effective activists on behalf of justice—Bishop Tutu, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Dorothy Day, and John Paul II—were ardent believers in the resurrection of Jesus.

A second great implication of the resurrection is that heaven and earth are coming together. As I’ve argued often before, many Christians today remain haunted by the Platonic view that matter and spirit are opponents and that the purpose of life is finally to affect a prison-break, releasing the soul from the body. This might have been Plato’s philosophy, but it has precious little to do with the Bible. The hope of ancient Israel was not a jail-break, not an escape from this world, but precisely the unification of heaven and earth in a great marriage. Recall a central line from the prayer that Jesus bequeathed to his church: “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.” The bodily resurrection of Jesus—the “first fruits of those who have fallen asleep”—is the powerful sign that the two orders are in fact coming together. A body, which can be touched and which can consume baked fish—has found its way into the realm of heaven, or to turn things around, heaven has reached down and transfigured a body, lifting it up into a higher pitch of perfection. Were the resurrection but a clever myth, the two dimensions would be as separate as ever.

Do not accept a watered-down, easy-to-believe ersatz of the resurrection faith. Let it be what it was always meant to be: dynamite.