The Libya Situation in Light of the Catholic Just War Tradition

By Rev. Robert Barron

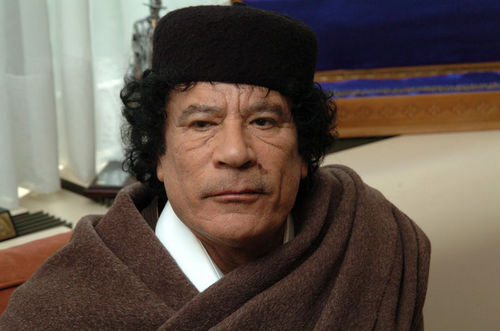

Why, in God’s name, are we entering a third war in the Middle East? America finds itself embroiled already in armed conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and now we have rained missiles down on Libya. When President Obama was asked about the Libyan incursion during a press conference in El Salvador, his answers were distressingly vague. As to the direction of the endeavor, the President said, “NATO is meeting today…to work out the mechanisms for command and control. I expect that over the next several days you will have clarity and a meeting of the minds of all those who are participating in the process.” One might be forgiven for wondering why greater clarity hadn’t been achieved prior to the dropping of bombs. And after assuring the gathered reporters that the mission in Libya was clearly defined as humanitarian assistance to the Libyan people and that our involvement would be a “matter of days and not weeks,” Obama admitted that as long as Qaddafi remains in power he will always pose a threat to his own people. In other words, the mission isn’t that clearly defined and the time of our involvement is more or less open-ended. Are we there to help the rebels? To protect innocent lives? To get rid of Qaddafi? To establish political stability in Libya? To assure that a democratic polity is established there? I’m not the least bit convinced that the administration knows, and if they don’t know, they won’t know when to declare victory and go home.

Why, in God’s name, are we entering a third war in the Middle East? America finds itself embroiled already in armed conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, and now we have rained missiles down on Libya. When President Obama was asked about the Libyan incursion during a press conference in El Salvador, his answers were distressingly vague. As to the direction of the endeavor, the President said, “NATO is meeting today…to work out the mechanisms for command and control. I expect that over the next several days you will have clarity and a meeting of the minds of all those who are participating in the process.” One might be forgiven for wondering why greater clarity hadn’t been achieved prior to the dropping of bombs. And after assuring the gathered reporters that the mission in Libya was clearly defined as humanitarian assistance to the Libyan people and that our involvement would be a “matter of days and not weeks,” Obama admitted that as long as Qaddafi remains in power he will always pose a threat to his own people. In other words, the mission isn’t that clearly defined and the time of our involvement is more or less open-ended. Are we there to help the rebels? To protect innocent lives? To get rid of Qaddafi? To establish political stability in Libya? To assure that a democratic polity is established there? I’m not the least bit convinced that the administration knows, and if they don’t know, they won’t know when to declare victory and go home.

Lest this discussion move exclusively in a “political” ambit, I would like to analyze the incursion into Libya in light of the Catholic just war theory. According to the Catholic social teaching tradition, going to war can be undertaken morally only when definite criteria are met. These are 1) declaration by a competent authority, 2) the presence of a just cause, 3) some proportion between the good to be achieved and the negativity of the war, 4) right intention on the part of those engaged in the conflict, and 5) a reasonable hope of success. One might argue that the first criterion has been met, since the President sanctioned our involvement upon the resolution of the United Nations to offer humanitarian aid to Libya.

In regard to the second standard, things get a good deal murkier. Traditionally, legitimating causes included the repulsing of an unjust aggression against one’s nation as well as the righting of wrongs in other nations or cities. Thus, in accord with that second specification, Thomas Aquinas said that a nation could go to war to punish a wicked king. Here we might see a ground for our pre-emptive moves against both Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi. Also, it would seem to provide a justification for sending troops into, say, Rwanda while the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of innocents was proceeding there without any interference. On the other hand, the Popes of the twentieth century, taking into account the terribly destructive nature of modern warfare, have ruled out the righting of wrongs criterion and have accepted only the repulsing of unjust aggression as a legitimating cause.

In applying the third criterion to the Libya situation, a good deal of ambiguity remains. No one doubts that Gaddafi, like Saddam Hussein, is a wicked man who has done terrible things to his own people, but one might well wonder whether the employment of the blunt instrument of the American military is in proportion to the achievement of the end of removing Gaddafi? The issue becomes even more complicated when we think of the long-term effects of invading a third Muslim country at a time when relations between our country and the Islamic world are already so strained. This was a major concern of Pope John Paul II at the time of our invasion of Iraq in 2003: how would the American attack on Iraq affect, not only the Iraqis, but the nearly one billion Muslims around the world? In regard to the fourth criterion—the right intention of the belligerents—I think that we can assume the American soldiers, for the most part, are going about their work responsibly and with a sense of moral purpose and proportion.

When we apply the fifth and final criterion, we come perhaps to greatest clarity. The Catholic just war tradition teaches that a war can be legitimately waged if and only if there is a reasonable hope of success on the part of the government that authorizes the fighting. For example, a war fought against an overwhelmingly more powerful opponent might be noble and brave, but it wouldn’t be just. But another reason for questioning the reasonable hope of success is the absence of a clearly defined mission and purpose. As I stated above, if we don’t know precisely what it is that we’re fighting for, we cannot, even in principle, determine when and whether we’ve won. A poorly-defined war is one that enjoys no reasonable hope of success. I believe that the strict application of this final criterion would render our action in Libya unjust.

I have found that a principle formulated by Gen. Colin Powell is both wise and congruent with the intentions of the Catholic just war tradition. Gen. Powell said that the American military should be unleashed only when three criteria are met: there is a defined objective, massive force can be brought to bear, and a clear exit strategy is in place. If any one of these factors is missing, the blunt instrument of the military should not be used. As far as I am concerned, none of Gen. Powell’s criteria are met in the current Libyan situation.

I am not a pacifist. I do think that sometimes, in our finite and conflictual world, violence has to be used in defense of certain basic goods. However, I believe that the criteria provided by the just war theory should be strictly rather than loosely applied. And I believe that such a strict application would rule out what our government is currently sanctioning in Libya.