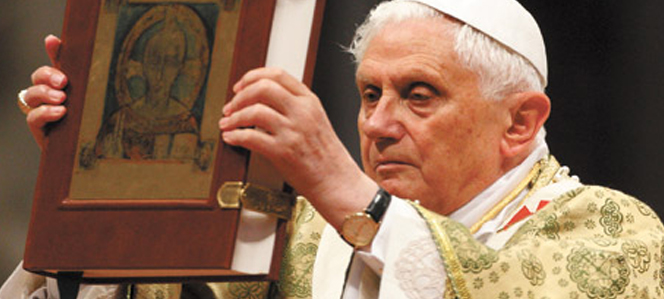

Pope Benedict and How To Read the Bible

By Rev. Robert Barron

The second volume of Pope Benedict’s masterful study of the Lord Jesus has just been published. The first volume, issued three years ago, dealt with the public life and preaching of Jesus, while this second installment concentrates on the events of Lord’s passion, death, and resurrection. As was the case with volume one, this book is introduced by a short but penetrating introduction, wherein the Pope makes some remarks about the method he has chosen to employ. What I found particularly fascinating was how Joseph Ratzinger develops a motif that he has preoccupied him for the past thirty years, namely, how biblical scholarship has to move beyond an exclusive use of the historical-critical method.

The second volume of Pope Benedict’s masterful study of the Lord Jesus has just been published. The first volume, issued three years ago, dealt with the public life and preaching of Jesus, while this second installment concentrates on the events of Lord’s passion, death, and resurrection. As was the case with volume one, this book is introduced by a short but penetrating introduction, wherein the Pope makes some remarks about the method he has chosen to employ. What I found particularly fascinating was how Joseph Ratzinger develops a motif that he has preoccupied him for the past thirty years, namely, how biblical scholarship has to move beyond an exclusive use of the historical-critical method.

The roots of this method stretch back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, to the work of Baruch Spinoza, Hermann Samuel Reimarus, and D.F. Strauss. The approach was adapted and developed largely in Protestant circles in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuires by such figures as Julius Wellhausen, Albert Schweitzer, Rudolf Bultmann, and Gerhard von Rad. Upon the publication of Pius XII’s encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu in 1943, Catholic scholars were given permission to use the historical-critical method in the analysis of the Bible, and a whole generation of gifted Catholic historical critics subsequently emerged: Joseph Fitzmeyer, Roland Murphy, Raymond E. Brown, John Meier, and many others.

At the risk of over-simplifying a rather complex and multivalent method, I would say that historical criticism seeks primarily to discover the intentions of the human authors of the Bible as they addressed their original audiences. It endeavors to know, for instance, what the author of the book of the prophet Isaiah wanted to communicate to those for whom he was originally writing his text. It wants to understand what, say, an Israelite community in 5th century B.C. Palestine expected, hoped for, or was able to hear; or it seeks to grasp, for example, the theological intentions of Matthew or John as they composed their Gospels. Accordingly, historical criticism is extremely sensitive to the cultural, political, and religious setting in which a given biblical author operated as well as to the particular literary forms that he chose to utilize.

Now it would be foolish to deny the value of the historical-critical method. When employed by responsible and faithful scholars, it has yielded tremendous fruit. One of its principal advantages is that it grounds our interpretation of the Bible in the rich soil of history. The Hebrew and Christian Scriptures are not predominantly mythological in form. By this I mean that they do not trade in timeless, ahistorical truths; rather, they convey how God has interacted with very real people across many centuries. Relatedly, the historical-critical method has allowed us to see through some of the distorting layers of interpretation that have been imposed on the Bible throughout the tradition and to return to the bracing truth of the texts themselves as they were originally meant to be read. Again and again, in both his pre-Papal and Papal writings, Joseph Ratzinger has affirmed the permanent value of this approach to the Scriptures.

However, he has also remarked the shadow side of this method and has consequently cautioned against a one-sided use of it. The first problem he notices is that the method, precisely in the measure that it concentrates so exclusively on the intention of the human author, can easily overlook the intention and activity of the divine author of Scripture. To be sure, Catholic biblical theology does not have a naïve appreciation of God’s authorship of the Bible, as though God simply dictated his words to robotic human instruments. Nevertheless, it holds to God’s inspiration of the whole of the Bible and hence defends the claim that God, in a very real sense, is the principal author of the biblical books. What follows from this claim is that the Scriptures as a whole have a coherency and are marked by discernible patterns and trajectories—all traceable to the intention of a supernatural agent. A significant limitation of the historical-critical method is that its hyper-focus on human authorship tends to leave us with a jumble of at best vaguely related texts, each with its own distinctive finality and meaning. We have, in a word, what Isaiah meant and what the author of the book of Job meant and what Mark and Paul meant—but not what God means across the whole of the Bible.

A second and related limitation is that the historical-critical method, precisely by looking so intently at the meaning of the biblical texts in their time, tends to leave them locked in history and hence unable to speak across the ages to us. We might uncover fascinating truths about what the Psalms meant for their original audience, but unless we discover what, through God’s spirit, they mean for us now, they are simply relegated to the status of ancient poems.

And this is why Pope Benedict wants to recover what he calls a “theological hermeneutic” that can be used along with the historical-critical method of interpretation. This theological approach is similar to the method that the church fathers used in interpreting Scripture. It takes with utmost seriousness the inner coherency of the Bible, born of its divine authorship, and it assumes that God’s word is given ever new illumination through the theological, dogmatic, and spiritual tradition of the church. In point of fact, Pope Benedict proposes his now two-volume study of Jesus as the fruit of both the historical-critical and theological methods of reading and hence as a model for future scholarship of the Bible. Benedict’s books are filled with important insights about Jesus, but I have a suspicion that the most lasting contribution he has made through this project is a re-shaping of the way we read the Bible itself.