Thirty years ago, on November 12, 1993, eight fighters entered a single elimination tournament to determine who would be the first Ultimate Fighting Champion (UFC). In the early UFC matches, there were no weight classes, no time limits, and no points to determine who had won the fight. The winner was determined by a knock-out, by a fighter admitting defeat via a submission, or by the fighter in his corner throwing in the towel to end the fight.

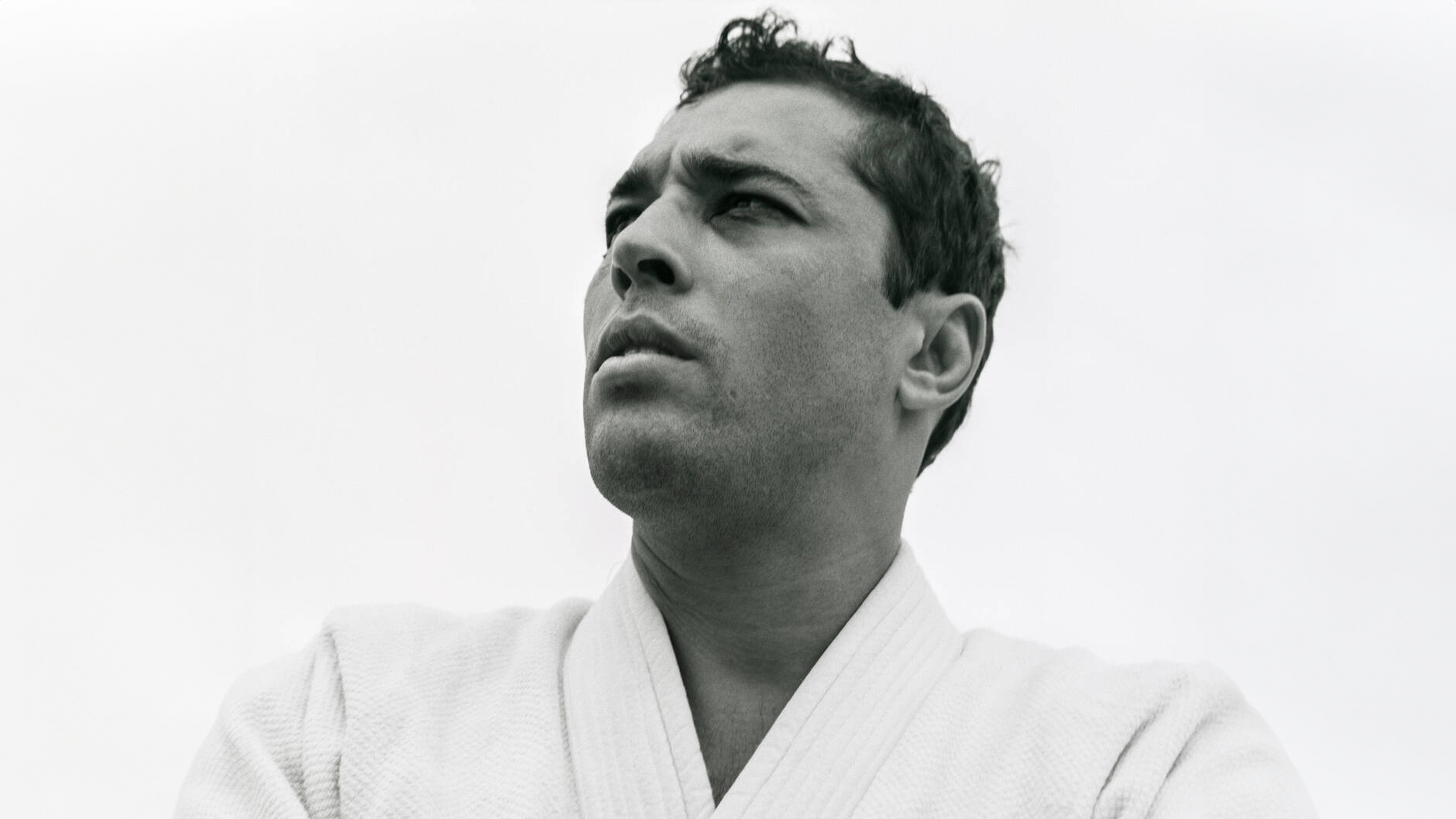

The UFC arose out of a question: Which martial art would triumph in an actual fight? The first UFC featured representatives of Sumo, Kickboxing, Karate, Tae Kwon Do, Boxing, Savate, and Shootfighting. Jiu-Jitsu was represented by Royce Gracie who pointed out that the UFC was “a quest to find out which style of martial arts is the best. Other people say their style is the best; we say ours is the best. There’s only one way to find out. No rules, no time limit, no gloves, no weight division. Let’s jump in a cage and fight until somebody quits.”

In one night, Gracie, who weighed in at 180 pounds, faced professional boxer Art Jimmerson, who weighed 196 pounds; professional shoot wrestler Ken Shamrock, tilting the scales at 220; and karate black belt and kickboxer Gerard Gordeau, weighing in at 216. Royce submitted them all to become the first UFC champion. He went on to earn two more UFC championships, and he would defeat even bigger opponents, including 235-pound taekwondo black belt Kimo Leopoldo and former collegiate All-American and world champion wrestler Dan Severn, who tilted the scales at 250 pounds, 75 pounds more than Gracie.

Jiu-Jitsu is not just a matter of the head, but of the heart, not just a matter of the mind, but of the body.

How did Royce Gracie defeat not just one but multiple Goliaths? The answer was Jiu-Jitsu, a martial art emphasizing not strength but leverage, not power but off-balancing, and not speed but timing. Jiu-Jitsu is designed, not as a sport, but for self-defense against stronger, bigger, and more athletic attackers.

Jiu-Jitsu emphasizes the value of embodied practices embedded in a tradition. You learn Jiu-Jitsu from a Master who has undergone ten years (or more) of rigorous training to become a black belt. From his youngest days, Royce learned Jiu-Jitsu in Brazil from his father Helio Gracie. Helio had himself participated in many no-holds-barred fights, Vale Tudo (Everything Allowed) matches against larger and stronger opponents. Helio learned and adapted Jiu-Jitsu from the Japanese fighter Mitsuyo Maeda, who learned from Kanō Jigorō, the founder of the Kodokan in Japan. The origins of Jiu-Jitsu go all the way back to the martial arts used by the Samurai in the late twelfth century.

In this emphasis on tradition, Jiu-Jitsu contains a valuable insight. Some modern minds are tempted to think that what is newer is always better, that the latest is the best, and that there is nothing worse than conserving tradition. But to learn Jiu-Jitsu is to enter into a community shaped by traditional practices dating back to the Samurai. No one can learn Jiu-Jitsu from a book or from a theory thought up in a hot room alone. To learn Jiu-Jitsu is to learn from an instructor how a move feels. It is not just a matter of the head, but of the heart, not just a matter of the mind, but of the body. To learn Jiu-Jitsu is to form yourself by practices inherited by tradition.

The value of learning from tradition applies also outside the context of a UFC octagon. In his presentation, “The Secret of our Success: Trust Tradition,” Harvard professor of evolutionary biology Joseph Henrich notes:

Cultural evolution is often much smarter than we are. Operating over generations as individuals unconsciously attend to and learn from more successful, prestigious, and healthier members of their communities, this evolutionary process generates cultural adaptations. Though these complex repertoires appear well designed to meet local challenges, they are not primarily the products of individuals applying causal models, rational thinking, or cost-benefit analyses. Often, most or all of the people skilled in deploying such adaptive practices do not understand how or why they work, or even that they “do” anything at all. Such complex adaptations can emerge precisely because natural selection has favored individuals who often place their faith in cultural inheritance—in the accumulated wisdom implicit in the practices and beliefs derived from their forbearers—over their own intuitions and personal experiences.

G.K. Chesterton shared a similar insight, “Don’t ever take a fence down until you know the reason it was put up.”

The costs of ignoring tradition are steep. As Thomas Sowell notes, “Advice to the young: You don’t have to listen to anybody. You can learn everything from your own personal experience. Of course, you will be at least 50 years old by the time you know what you need to know at 25.”

The value of practices shaped by tradition is also found in the spiritual life. Rather than reinvent the wheel, we can learn from the experience of the greatest saints and sages of ages past. As Pope Benedict noted, “Tradition is not the transmission of things or words, a collection of dead things. Tradition is the living river that links us to the origins, the living river in which the origins are ever present, the great river that leads us to the gates of eternity.” We have a fighting chance against the Goliaths in our lives only if we learn from the best of the past.