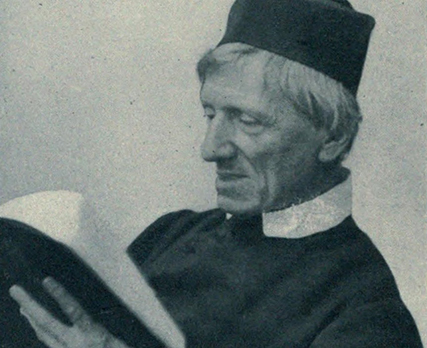

As I compose these words, I am preparing to leave for Rome, where I will attend the canonization Mass for John Henry Newman, and then for Oxford, where I will give a paper on Newman’s thought in regard to evangelization. Needless to say, the great English convert is much on my mind these days. As I read the myriad commentaries on the new saint, I’m particularly struck by how often he is co-opted by the various political parties active in the Church today—and how this co-opting both distorts Newman and actually makes him less interesting and relevant for our time. I should like to show this by drawing attention to two major themes in Newman’s writing—namely, the development of doctrine and the primacy of conscience.

St. John Henry Newman did indeed teach that doctrines, precisely because they exist in the play of lively minds, develop over time. And he did indeed say, in this epistemological context, “to live is to change and to be perfect is to have changed often.” But does this give us license to argue, as some on the left suggest, that Newman advocated a freewheeling liberalism, an openness to any and all change? I hope the question answers itself. In his Biglietto speech, delivered upon receiving the notification of his elevation to the Cardinalatial office, Newman bluntly announced that his entire professional career could be rightly characterized as a struggle against liberalism in matters of religion. By “liberalism” he meant the view that there is no objective and reliable truth in regard to religious claims. Moreover, Newman was keenly aware that doctrines undergo both legitimate development and corruption. In other words, their “growth” can be an ongoing manifestation of truths implicit in them, or it can be a devolution, an errant or cancerous outcropping. And this is, of course, why he taught that a living voice of authority, someone able to determine the difference between the two, is necessary in the Church. None of this has a thing to do with permissiveness or an advocacy of change for the sake of change.

In point of fact, the development of doctrine, on Newman’s reading, is not so much a pro-liberal idea as an anti-Protestant one. It was a standard assertion of Protestants in the nineteenth century that many doctrines and practices within Catholicism represent a betrayal of biblical revelation. They called, accordingly, for a return to the scriptural sources and to the purity of the first-century Church. Newman saw this as an antiquarianism. What appears unbiblical within Catholicism are, in fact, developments of belief and practice that have naturally emerged through the efforts of theologians and under the discipline of the Church’s Magisterium. His implied interlocutor in the Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine is not the stuffy Catholic traditionalist, but the sola Scriptura Protestant apologist.

The second issue that particularly draws the attention of commentators today is the role of conscience. Conscience is one of the master ideas in Newman’s corpus; he discusses it from beginning to end of his career and it is the hinge on which many of his major teachings turn. One of the most cited mots of Newman’s is his clever quip regarding the authority of the Pope: “If I am obliged to bring religion into after-dinner toasts, I shall drink—to the Pope, if you please—but to conscience first, and to the Pope afterwards.” I cannot tell you how many pundits have run with that offhanded remark, concluding that Newman was flouting the Pope and advocating a moral subjectivism. Nothing could be further from the truth. In his late career masterpiece, The Grammar of Assent, Newman refers to conscience as “the aboriginal vicar of Christ in the soul”—that is to say, the felt presence of a “judge holy, just, and powerful . . . an all-seeing, supreme governor.” Conscience is not the voice of the individual himself, but rather the Voice of Another, who exercises sovereign authority, who makes demands and furnishes both reward and punishment. The Pope is indeed the Vicar of Christ in a formal and institutional sense, and the conscience is Christ’s representative in an even more intense, more interior, and “aboriginal” mode. This is why toasting the latter before the former by no means implies that they exist in tension with one another; just the contrary.

Now, am I implying through this analysis of two of Newman’s central notions that present-day conservatives are right in their claiming of the new saint? Well, sensible conservatives can and should do so, but there are excessive traditionalists in the Catholic Church against whom Newman stands athwart. The idea of real doctrinal development does indeed run counter to a Catholic antiquarianism that would see dogmas as changeless objets d’art, and the assertion of the primacy of conscience does indeed run counter to a fussy and hyper-judgmental legalism. As I suggested above, the setting of these discussions within the context of Newman’s own time permits us to see how his resolution of these complex matters takes us far beyond the exhausted left/right categories that dominate the present debates.