When Damien de Veuster arrived in Hawaii in 1864, he found an island-community beset by infections. Over the years, travelers and seamen had introduced diseases like influenza and syphilis. Yet none were as bad as Hansen’s Disease, more commonly known as leprosy. First reported in Hawaii in 1840, leprosy devastated people in many ways. First, because the disease was highly contagious and untreatable until the 1930s, people contracting it had no hope of recovery. This often led to deep depression among its sufferers. Second, leprosy caused a progressive degeneration of their skin, eyes, and limbs. It thus disfigured people and eventually immobilized them. Finally, few diseases isolated people from their communities as much as leprosy. Sufferers were seen as outcasts and cautioned to stay away from everyone else.

In 1866, to curb the spread of the disease, Hawaiian authorities decided to consign lepers to an isolated community on the island of Molokai. On three sides, the colony, called Kalaupapa, bordered the Pacific Ocean, and the fourth side featured massive, 1,600-foot cliffs. Once the lepers were out of sight and no longer a threat to the general population, the government turned a blind eye to their basic needs. Shipments of food and supplies slowed down, and the government removed most of its personnel. The result was a highly dysfunctional community marked by poverty, alcoholism, violence, and promiscuity.

Puritan missionaries became convinced that leprosy stemmed from the people’s licentiousness. But Damien knew that wasn’t true. He believed the people on Molokai were basically good, not corrupt, and that sin did not cause the spread of the disease.

In time, Damien came to see the neglected colony as the answer to his boyhood longings for adventurous missionary work. He asked the local bishop for permission to go to Molokai, and the bishop not only granted approval, but personally accompanied Damien to the island. He introduced Damien to the 816 community members as “one who will be a father to you and who loves you so much that he does not hesitate to become one of you, to live and die with you”.

This introduction didn’t surprise Damien, who had no illusions about what his mission would entail. He knew working in the disease-ridden colony virtually guaranteed that he would become infected, too. Yet he never wavered in his commitment.

At first, the conditions around the lepers proved overwhelming. Damien often felt as if he had opened a door to hell. Victims wandered about, their bodies in ruin and their constant coughing the island’s most familiar sound. Damien could hardly bear the stench:

“Many a time in fulfilling my priestly duties at the lepers’ homes, I have been obliged, not only to close my nostrils, but to remain outside to breathe fresh air. To counteract the bad smell, I got myself accustomed to the use of tobacco. The smell of the pipe preserved me somewhat from carrying in my clothes the obnoxious odor of our lepers.”

Eventually Damien overcame the distressing sights and smells. His superiors had given him strict advice: “Do not touch them. Do not allow them to touch you. Do not eat with them.” But Damien made the decision to transcend his fear of contagion and enter into solidarity with the Molokai lepers. He committed to visit every leper on the island and to inquire of their needs.

One early realization was that to show the lepers the value of their lives, he had to first demonstrate the value of their deaths. So he built a fence around the local cemetery, which pigs and dogs regularly scavenged. He also constructed coffins and dug graves, committing that each leper, even if marginalized throughout his life, would receive a decent burial upon death. This had a remarkably uplifting effect on the community.

Damien also devoted his attention to the sick. He brought the sacraments to bedridden lepers. He washed their bodies and bandaged their wounds. He tidied their rooms and did all he could to make them as comfortable as possible.

What surprised the lepers most was that Damien touched them. Other missionaries and doctors shrank from the lepers. In fact, one local doctor only changed bandages with his cane. But Damien not only touched the lepers, he also embraced them, he dined with them, he put his thumb on their forehead to anoint them, and he placed the Eucharist on their tongues. All of these actions spoke volumes to the dejected lepers. They showed that Damien didn’t want to serve them from afar; he wanted to become one of them.

Damien was careful never to present himself as a messianic figure. soaring in from a higher, more privileged position. He invited lepers to join in the work, turning his service to the community into an act of solidarity. He had them help build everything from coffins to cottages. When the colony expanded along the island’s peninsula, his leper friends helped construct a new road. Under his supervision, the lepers even blasted away rocks on the shoreline to create a new docking facility. Damien also taught the lepers to farm, raise animals, play musical instruments, and sing. Although the lepers were used to being patronized or bullied, Damien spread among them a new cheer and sense of worth.

This refreshing spirit impressed visitors to the island. “I had gone to Molokai expecting to find it scarcely less dreadful than hell itself,” wrote Englishman Edward Clifford in 1888, “and the cheerful people, the lovely landscapes, and comparatively painless life were all surprises. These poor people seemed singularly happy.”

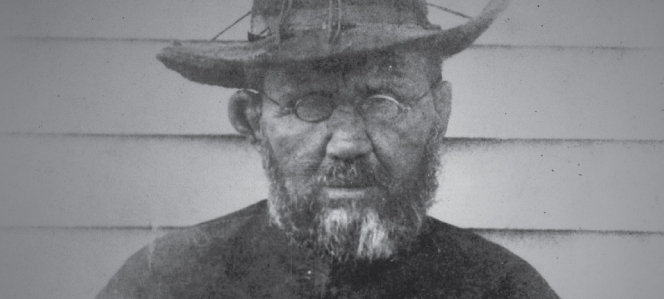

Despite the idyllic community Damien had built through a decade of work, the moment he feared finally arrived in December 1884. One day, while soaking his feet in extremely hot water, Damien experienced no sensation of heat or pain—a tell-tale sign that he had contracted leprosy. The disease quickly developed, causing Damien to write to his bishop with the news: “Its marks are seen on my left cheek and ear, and my eyebrows are beginning to fall. I shall soon be completely disfigured. I have no doubt whatever of the nature of my illness, but I am calm and resigned and very happy in the midst of my people. The good God knows what is best for my sanctification. I daily repeat from my heart, ‘Thy will be done.’”

Soon, he also wrote home to his brother: “I make myself a leper with the lepers to gain all to Jesus Christ.”

Even before contracting the disease, Damien spoke of himself and the people of Molokai as “we lepers.” He identified closely with those he came to serve and thus, before and after the disease, offered a powerful, concrete expression of solidarity. And it was for that reason he become known not by his homeland, but by the island community he served—St. Damien of Molokai, patron of lepers.