In the nineties, the True Love Waits movement was making its way through youth groups around the world. Young men and women signed small cards, vowing to commit their sexual purity to God and to pray for all of those who had sinned sexually. The movement spurred purity rings, songs, books, and more.

In the same decade, the book I Kissed Dating Goodbye by Joshua Harris became a bestseller, to date selling over a million copies which is a great feat for any Christian work. In 2018, Harris retracted his former beliefs in dating and asked for the publisher of the book to halt any reprints. More on that later.

The book and the movement were a large part of what we now know as “purity culture” and it was a very big part of my youth. I signed the cards. I read the book. And inevitably, I came to view dating and conjugal love with repudiation. Dating became something to avoid, and conjugal love became something that I downright feared. In the end, I became irrationally ashamed of everything associated with the body.

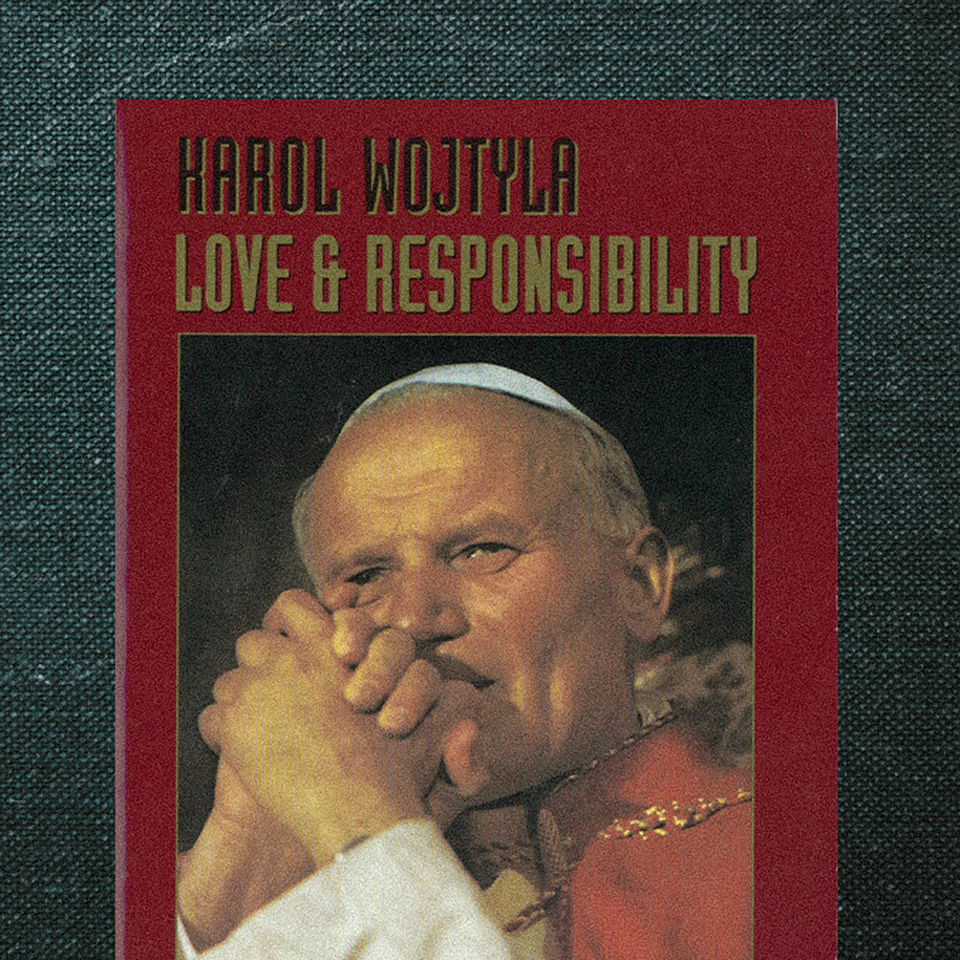

Three years ago, I attended a philosophy seminar on the subject of Love, Sex, and the Human Person. Already a strong believer in the innate dignity of the human person, I had yet to dive into the pre-pontifical writings of St. John Paul II. Better said, I didn’t know anything about Karol Wojtyła. That was the summer that I met him, while reading his book Love and Responsibility.

Love and Responsibility taught me that utilitarianism had not only invaded the material world but it had distorted my understanding of the human person, of anthropology itself. Modern men and women began to view one another as objects of use instead of subjects of gift. Utilitarianism, which values usefulness over being, means over ends, had become the gauge for my worth. What do I contribute? Am I useful? What do I have to offer? And more often than not, I came up with nothing. I was not valued. And, if I did not value myself, I could not value the other. The lens in which we see the world is the same lens in which we view ourselves. I had adopted the opposite commandment of love, which, as Wojtyła insightfully poses, is not hate but use.

Now for the chapter that changed my life.

In the chapter “The Person and Chastity,” Wojtyła dives into what he calls the metaphysics of shame, defining it as “when something which of its very nature or in view of its purpose ought to be private passes the bounds of a person’s privacy and somehow becomes public.” He goes on to say that modesty is a natural tendency. As sexual values are awakened in the human person, the natural tendency is to conceal—not because of their negative value but because of their immensely positive value.

More deeply, shame has a dual nature. It conceals for the purpose of protection (i.e., modesty). In a positive sense, it is a notion of reverence: a recognition of the inexhaustible value of the human person. We are all mysteries to be discovered, and these discoveries are met with the positive shame that we simultaneously desire to be known and to know one another but are also incapable of knowing all there is to know about one another. It is an invitation to love.

Wojtyła says that shame is “swallowed up by love, dissolved in it.” He doesn’t mean that shame is erased by love but that love exists with shame as a natural defense against mere use. Shame should not diminish the value of the person but should veil that which is meant to be secret without obscuring one’s innate dignity.

How did this change my life? I was seven years into my marriage at this point and still unearthing the damage of the purity culture. It was something that I wasn’t even able to name until I picked up Wojtyła’s book. But I had seen the distortions of it, even before marriage, and it had nothing to do with sex.

My husband, Jason, and I were dating, and my mother, suffering with kidney disease, was facing another kidney failure and I was going to meet her at the hospital to discuss next steps with her neurologist. It was going to be a long drive, and my heart was wrecked. Yet I couldn’t bring myself to show that to Jason.

Looking back, I know that I didn’t want to reveal myself, my fears, to him because I was ashamed—not of my mother, not of her illness, but because I didn’t want to make him intimate with my pain or even intimate with my fragility. Purity culture had taught me that any crack in the porcelain—whether sexually, mentally, or emotionally—was enough to be deemed unlovable. Any sort of vulnerability was contrary to maintenance of purity. I was ashamed of my own humanity.

Inevitably, I did tell Jason, but I made him turn around while I did so, afraid that his eyes would reveal his disdain for my vulnerability. After I blurted out what was ahead for my mother, he turned and embraced me. He walked with me through her news, and the greatest memory of that trip was driving back to our hometown with him while I wept on his shoulder. My shame was swallowed up in his love.

The profundity of shame in its proper sense—as concealment of that which is valuable, as reverence—upholds dignity. Conversely, when it is distorted, the consequences not only negatively impact dignity but can also damage our own spiritual lives. After all, the wholeness of the person lies in their entire being—spirit, mind, and body. When one part is negatively hidden, the whole being suffers.

I Kissed Dating Goodbye was likely such a great success because, though the approach was extreme, Christians were looking for solid guidance in a sexually revolutionized society that had gone all-too utilitarian. Harris posited that mainstream dating wasn’t working, so the entire thing should be thrown out and replaced with what he called “biblical courtship.”

Instead of encouraging a desire to protect what is valuable, Harris’ approach unwittingly instilled fear. One extremely impactful image from his book was an image of men at the altar holding hands with all of their past partners, bringing all of that pain into their marriage because they have given themselves away, and away, and away, and thus become diminished persons because of it. That image wounded my understanding of grace.

True love, authentic love will not drag your missteps to the altar. It will not shove into the darkness that which is good, and it will not impose fear where there should be the more positive “shame” that comes with reverence for God, oneself as God’s creation, and the people all around us. Authentic love expands who you are—innately good and capable of being redeemed.