The Fire at Namugongo

By Rev. Robert Barron / From Our Sunday Visitor

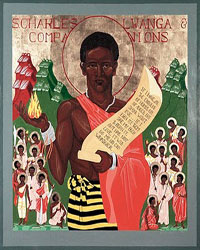

In 1879, the first Catholic missionaries arrived in the heart of Africa, in what is now the nation of Uganda. They catechized and preached and in a few years had made a number of converts, especially among the young. The most prominent of these were a group of men and boys who served as pages to the court of King Mwanga II. This king had initially been supportive of the missionaries, but his attitude quickly changed when he discovered how seriously his Christian pages took the moral demands of their new faith. Accustomed to getting whatever he wanted, Mwanga solicited sexual favors from several of his courtiers. When they refused, he presented them with a terrible choice: either renounce their Christian faith or die. Though they were new converts and though they were very young, the pages, to a man, refused to deny their Christianity. Joseph Mukasa Balikudembe was killed outright by the king himself, and the rest were led off on a terrible death march to the place of execution, many miles outside the capital city. On the way, the condemned passed the home of the priest who had baptized and catechized many of them. One can only imagine the profoundly conflicting feelings of pride and anguish that the priest must have experienced as he watched this procession. Witnesses said that the young men showed enormous resolution on the march and that the youngest, a boy named Kizito, actually chattered and laughed with this friends as he walked. When they arrived at the place of execution, a spot called Namugongo, they were put to death, some by spear but most by fire. The leader of the group, Charles Lwanga, all of twenty-five years old, asked permission to prepare the pyre himself. After arranging the wood, he lay down and endured a slow torture in silence, crying out “Oh God!” only at the very end.

In 1879, the first Catholic missionaries arrived in the heart of Africa, in what is now the nation of Uganda. They catechized and preached and in a few years had made a number of converts, especially among the young. The most prominent of these were a group of men and boys who served as pages to the court of King Mwanga II. This king had initially been supportive of the missionaries, but his attitude quickly changed when he discovered how seriously his Christian pages took the moral demands of their new faith. Accustomed to getting whatever he wanted, Mwanga solicited sexual favors from several of his courtiers. When they refused, he presented them with a terrible choice: either renounce their Christian faith or die. Though they were new converts and though they were very young, the pages, to a man, refused to deny their Christianity. Joseph Mukasa Balikudembe was killed outright by the king himself, and the rest were led off on a terrible death march to the place of execution, many miles outside the capital city. On the way, the condemned passed the home of the priest who had baptized and catechized many of them. One can only imagine the profoundly conflicting feelings of pride and anguish that the priest must have experienced as he watched this procession. Witnesses said that the young men showed enormous resolution on the march and that the youngest, a boy named Kizito, actually chattered and laughed with this friends as he walked. When they arrived at the place of execution, a spot called Namugongo, they were put to death, some by spear but most by fire. The leader of the group, Charles Lwanga, all of twenty-five years old, asked permission to prepare the pyre himself. After arranging the wood, he lay down and endured a slow torture in silence, crying out “Oh God!” only at the very end.

I’m sure that practically any objective observer of that terrible scene would have concluded that Christianity was finished in that part of Africa. The remaining Christians—a tiny minority surrounded by hostile enemies, including the King himself—would be terrorized by what happened at Namugongo, and many of them undoubtedly would surrender whatever allegiance they had to the new faith brought by the white missionaries. But there is a peculiar logic that obtains in matters supernatural, a logic of paradox, reversal, and surprise. That which should stifle Christianity in point of fact makes it grow stronger, precisely because the faith is correlative to a reality that transcends nature and the dynamics that govern ordinary experience. The church father Tertullian caught this in his famous adage to the effect that the blood of martyrs is the seed of Christians. I’m sure that some who saw or heard of the executions at Namugongo abandoned their faith, but many others were galvanized by the courage of those young witnesses. And as the story was passed on, people came not only to admire the valor of those who died but more importantly to understand that, as Evelyn would put it, “the supernatural is the real.” The Catholic church in Africa didn’t die at Namugongo; it came to life there.

On June 3rd, the feast of the Ugandan martyrs, a festive liturgy, attended by over 500,000 people takes place at Namugongo, just adjacent to the site where Charles Lwanga uttered his plaintive, “Oh God.” It was one of the great privileges of my life to have assisted recently at that Mass, as part of the filming for my series on Catholicism. As the massive crowd assembled, choirs from many different parts of Africa sang and swayed, and a tremendous spirit of prayerfulness obtained. About fifteen minutes before the formal commencement of the Mass, a liturgical procession—the most wonderful I’ve ever witnessed—took place. It began with three dignified young men, wearing the formal garb of acolytes, and just behind them came a parade of female dancers, dressed in the traditional tribal costumes of Africa and dancing and gryrating joyfully to the music. Then came a team of male dancers, wearing leopard skins and feathers, and jangling ankle bells as they stepped. Behind them came a long line of priests and bishops, swathed in red chasubles, evocative of the blood shed by the young martyrs. The general mood that this created—almost overwhelming in its power—was joy, triumph, victory. As I watched all of this unfold, I confess that several times tears came to my eyes, for I could see, beyond the procession and beyond the crowd, the top of the basilica constructed on the site of Charles Lwanga’s execution. As that brave young Christian uttered his dying “Oh God” on that spot so many years before, could he ever imagined that one day a half a million African Catholics would gather there in festive celebration of the faith for which he gave his life? Could he ever have imagined that, in the year 2010, there would be 400,000,000 Christians in Africa?

The blood of the martyrs is indeed the seed of Christians. Charles Lwanga, you won!