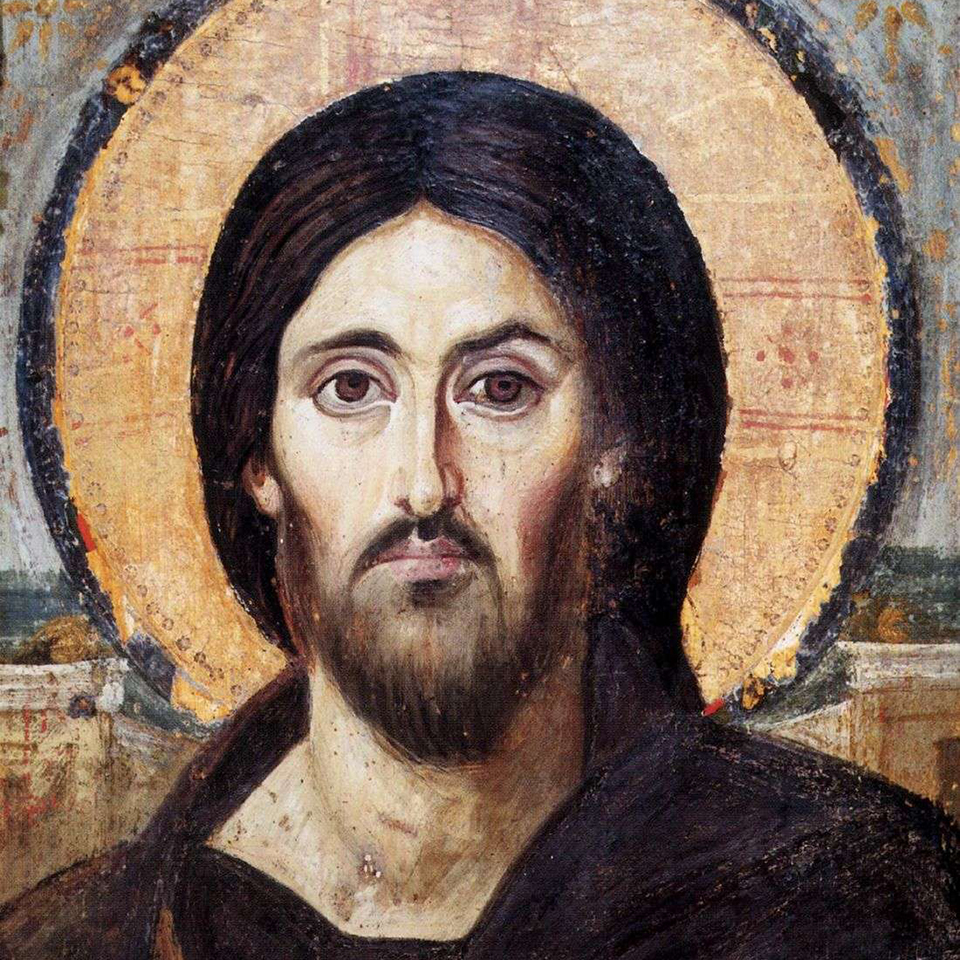

When I first met Fr. Steve Grunow, CEO of Word on Fire, I was struck by a strange and beautiful image on his desk. It was an Icon of the Christ Pantocrator of Mt. Sinai, and the Christ who stared at me was both of this world and beyond it.

Stranger than the image, however, was my feeling that Christ was staring right at me from within the depths of the icon. When I asked, Father Steve kindly explained the theology of the icon, cluing me in on how effectively they can help to engage us and deepen our faith, and even teach us.

Like the Gospels, icons present “the form of Christ” who reveals the “form of God”. With this in mind, I’d like to argue that icons deserve a more prominent role in religious education.

One of my best teachers used icons as a pedagogical tool in class. Fr Paolo Prosperi, former assistant professor of patristics at the Pontifical John Paul II Institute in Washington, D.C., and priest of the Fraternity of St. Charles Borromeo, opened every Christology class by explaining an icon and how it threw light on some aspect of the mystery of Christ. Having studied patristics at the Pontifical Oriental Institute in Rome, later living in Russia for many years to learn Russian and to study its culture and icons, most of the icons he taught in class were Russian. I particularly remember his explanation of Rublev’s icon of the Trinity and how it helped me to better understand the Trinitarian dimensions of the liturgy, salvation history, and Christian prayer. From then on, icons became a visual catechesis for me.

Since I cannot do justice to the profundity of this icon, I refer you to Paul Evdokimov’s Art of the Icon for further explanation, but Rublev’s Trinity is a depiction of the Biblical story of the three pilgrims who visit Abraham under the oak of Mamre. It is a penetration into the deeper meaning of that story, which offers us a glimpse of the Trinity.

The icon depicts the dynamism and stability of the Trinity. The movement within the icon reflects the exitus-reditus (going out and return) of salvation history which also happens to be the movement of Christian prayer: through Christ we have access to the Father by the Spirit (Ephesians 2:18) which is also, in a way beyond words, the eternal movement of the Trinity.

There are various ways of reading the icon, but here Trinity. I will follow Russian theologian Paul Evdokimov’s traditional reading of it. The far left angel is the Son; the middle angel is the Father, and the far right angel is the Holy Spirit.

Above each angel’s head is a biblical image: Above the Father’s head is the tree of life; above the Holy Spirit, the holy mountain and above the Son, a building representing the Church.

The bodies of each angle are fourteen times the size of the head which is double our human proportions, signifying the supernatural dimension of each person. Each angel looks identical, denoting the equality of each, and they look both female and male, signifying that God is beyond biological sex. The head of the Father and the Son lean toward each other with the Spirit partaking in their union. These gestures outline the dynamics of the spiritual life.

The geometric shapes of the icon (the rectangle, the triangle, the circle, and the cross) are important, too. The table, with its four corners, represents the earth fulfilled by the four Gospels. This white table (the Word) supports the chalice (a symbol of the Eucharist) that signifies the profound revelation that “God so loved the world that he sent his only Son” (John 3:16). A cross appears within the vertical line of the whole composition, meeting the horizontal line between the halos of the Son and the Holy Spirit. This cross is inscribed in the sacred circle of the Trinitian love. The Son and the Spirit are the two hands of the Father which embraces the whole cosmos in himself.

The line following the outer contours of the three angels forms a perfect circle, a sign of God’s eternity. The inner contours of the three angels form a chalice, communicating the central revelation of the icon: God’s eucharistic love for us. The lines of the Father near the Son and Spirit are convex lines, meaning the Father outwardly expresses himself in the Son and the Spirit. The outlines of the Son and Spirit are concave; they obediently, inwardly listen to the Father. Notice that the Son’s posture is attentive, as if listening to the Father.

Unsurprisingly, because nothing in iconography is done with caprice, the colors have meaning, too: The Father’s colors are deeper than the other two because God’s revelation in the Son and Spirit is lighter and gentler than the full depths of the Father. The deep purple (divine love), the blue (divine truth), and the firey gold of the wings (divine abundance) come together perfectly in the Father, but they would overwhelm us. The Son softens the colors of the Father in rose and light blue. The green (life) of the Spirit shows the Spirit as the principle of life, heavenly breath, which is in the Father’s utterance of his Word (the Son).

The Son with the Church (eschatologically complete in the Heavenly Jerusalem) is the end point of the entire icon. The holy mountain and tree of life (the cosmos) lean toward the Church. The Father and the Spirit lean toward the Son. There is much more to this icon, but I hope this brief exposition demonstrates the catechetical potential of icons.

Iconography follows a strict code. Not only must the iconographer be prayerfully in the spirit, but she must follow the rules of iconography depending on which event and/or person of salvation history she is painting. These rules have been passed on, iconographer to iconographer, since the beginning, and they have specific purposes geared toward assisting our prayer and understanding to reach out to heaven. Icons are not presentations of the artist’s creativity at all — this is why traditional icons go unsigned — but ultimately aids to Christian prayer. Iconography does develop with each iconographer just as Christian doctrine unfolds over time. But, the essential outlines of Christian revelation must remain intact.

Icons are difficult to create in that they must bring together nature and super-nature (the finite and the eternal). The icon of Christ Pantocrater, for instance, shows us the face of Jesus, direct and head on; any favoring of one side is a distortion of Christ.

Through Fr. Prosperi’s educational methodology and the central role icons had in it, I discovered that icons are a kind of divine pedagogy, a way of teaching that has an ancient pedigree in the Church. In the Bible, God teaches us not by starting with life experience – the starting point of much contemporary catechesis – but by forming a people to receive a divine image, ultimately the image of his Son. God does not ask us to paint a picture by ourselves –we often get it wrong, just think of the Golden Calf – but mercifully writes a perfect image (iconography – written image) for us in which the depths of our experience comes to light.

Fr. Prosperi’s methodology was very similar to an ever-present name here at Word on Fire: Hans Urs von Balthasar. The son of an ecclesial architect and an accomplished musician himself, he was a master of the arts who understood the priority of perception and the way art elevates the senses to a greater comprehension of the whole in Christ. He emphasized the revelatory power of the image, and lamented the iconoclasm (the destruction of images) in the contemporary Church. In his view, the faithful were either given no images or a bad images, and too many representations of Christ that over-emphasized his humanity at the expense of teaching his divinity, which has contributed to decades of poor catechesis.

Humans think in images. In an act of mercy, God has given us His Image to set us aright. Accordingly, religious education should use icons when meditating on the faith. In And Now I See, Bishop Barron writes, “The Christian tradition stubbornly and patiently walks around the icon of Christ, seeing it, describing it, speaking of it in various ways and with various audiences in mind, convinced that no one word, no one take, is sufficient to exhaust the “infinite richness of Christ.” Accordingly, there’s no richer means of enhancing religious education than on contemplating the icons of Christ, of his holy mother and the gospel stories, themselves.

Images matter. They can either distort the divine or authentically communicate it. Many pedagogical approaches foment idolatry by reducing the divine to this world, making it a dumb object that does not personally engage — or simply a projection of oneself ad one’s desires. In God Without Being, Jean Luc Marion remarks on the difference between the idol and the icon. The idol is “a mirror of our own desires”, never letting us transcend ourselves whereas the icon is “a visible mirror of the invisible”, leading the viewer into a true encounter with a divine other. The priority is not our gaze but the gaze on the face of the icon which opens up for us the divine world of prayer. Catechesis based on icons will help foster an encounter with Christ.

Many Eastern theologians lament the direction Western art went after the Renaissance when Christ and the saints were depicted more naturally. The nadir of this practice might be the “Christ, Liberator” painting, popularly known as the “Laughing Jesus,” found in many Catholic schools and parishes throughout the world, perhaps contributing to the incomplete understanding of Christ as the God-man, who is not merely human.

So, let us study the theology of icons, for they are great instruments of divine pedagogy. Students will be intrigued, as I was, and want to better know the Lord through them. Hopefully, this will help them to become living icons of the Lord. Icons have taught the faith in all ages. Catechesis is knowing the outlines and forms of Christ’s face in its many manifestations. Like Fr. Prosperi, foment encounters with the Lord by having icons present around us, and helping others to learn from them. Possibly then, those we encounter in classrooms or in daily life may say with St. John of Damascus, “I saw the human face of God, and my soul has been saved.”

In my next blog post, I will discuss why music is an effective catechetical tool for teaching salvation history, the theo-drama. Music, like all drama, combines tension and release. Stay tuned to learn why Mozart is not only great for babies but babes in the faith!