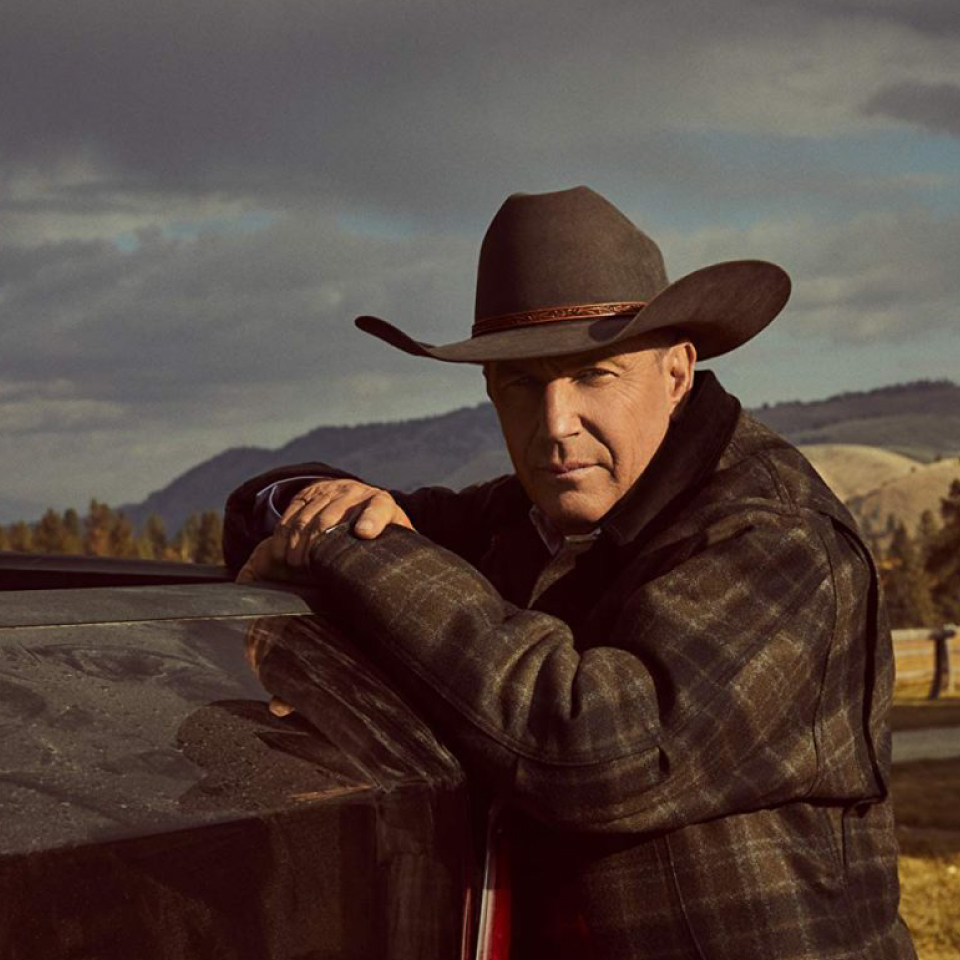

Growing up in a small town in Texas as the grandchild of farmers, the cowboy was often idolized as the picture of virtue and hard work. Though historically speaking my ancestors had their own struggles with Native American Indians, our home had a very appreciative view of the history of native peoples. The first Halloween costume I remember donning was that of “The Lone Ranger,” and many of my first memories of watching television with my family consisted of John Wayne, Ben Cartwright and his sons on Bonanza, and Lucas McCain in The Rifleman. Needless to say, I was beyond excited at the announcement of Kevin Costner’s Yellowstone, which seems to be a mixture of The Godfather and Bonanza. At first glance, Yellowstone is an action-packed drama about a patriarch protecting what has been his family’s for generations; however, at a deeper level, the show has much to critique about our modern notions of family, heroes, villains, and historical narrative.

John Dutton, the patriarch of the family, is the icon of the leather-skinned, tough-as-nails rancher. Each of his four children has their own demons to wrestle with, and many of those demons are a result of the hard upbringing of being a Dutton. From the sister being blamed for the death of her own mother, to a son being branded by his own father, the Dutton’s have more than a few familial skeletons that need to be reckoned with. Regardless of the horrendous past, somehow this family still finds a way to be loyal to John and the family ranch. As the show unfolds, you come to learn of several outsiders who want to take away what the family has worked for over so many generations: a certain way of life and view of the world.

On one side, you have the local American Indian tribe trying to take back the land of their ancestors. On another side, you have a progressive land developer who wants to build second homes for the uber-wealthy. So, much like the old westerns, you now have the cowboy, the American Indian, and the rich tycoon, who all want a piece of land. Each category of power provides its own philosophy of history and way of life. What the show most vitally offers is the problems with each category. The Dutton family wants to hold on to a glorious past that can’t exist anymore, especially given the fact that the ranch has not been able to turn a profit in almost a decade. This is of course offered with a slight jab, though not unfounded, at the current governmental structures and family farms. The American Indian tribe wants to resolve a generations-long grievance through land-grabbing and vengeance. However, grabbing land is not going to change the social ills of the reservation as it stands. The land developer wants to force “progress” on a people who want nothing to do with high-priced coffee shops and snobby, suit-wearing yahoos who’ve never had a calloused hand in their life. Each category is willing to lie, cheat, steal, and kill if that is what it takes for their vision to take place.

What I began to notice throughout the show was the display of Hegelian dialectic. Each category of power provides its own proposition or thesis of how the world ought to be. This thesis is countered by a different proposition, and this thesis-antithesis dialectic becomes violent as we await a potential synthesis. However, the problem of violence goes much deeper than how we understand history or how we understand progress. The violence, as is shown in Yellowstone, only begets more violence. The problem at the heart of the violence is a problem of self-identification. The Duttons define themselves by the land they own. The American Indians define themselves by the land that was stolen. And the land developer defines himself by the land he wants. Notice here that none of these categories define themselves by who they are. Their definition of self comes from the negation of another, the desire for power, or the vengeful need for retribution.

Yellowstone does a phenomenal job at knocking down a few of the iconic figures that we so often want to emulate. The cowboy, so often known as the icon of virtue or right, is portrayed as a spiteful, devious king-like landowner who is fearful of everyone around him, even his own children. The American Indian, known as one of the greatest warriors of human history with an allegiance to the sacred, is portrayed as a grown man acting like a child whose toy has been stolen from him. The successful businessman, so often seen as an ambitious man of the new age, is portrayed as a sniveling weasel who will stop at nothing for money. When a man or woman defines themselves by that which cannot ultimately fulfill them, we end up living out the vices of the villain rather than the virtues of the hero. Walker Percy was right to state that in a time of good and evil being flattened out, we have to portray evil in its highest sense through the everyday character in order to awaken the hearts and minds of today. We want the virtuous cowboy. We want the sacred Indian. We want the go-getting businessman. Sometimes the only way to remember the ideal is to see its opposite.

Being stuck in the past or blindly progressing forward are both problematic, as they deny the fundamental human problem. We ought to hold up icons of virtue in the cowboys, the Indians, and the businessman. However, we also ought to be keenly aware that humanity is messy, and the only way to move forward is through a “conservative progress.” We ought not forget who and what we are, but we also ought to fight for the betterment of the world. When we hold up either extreme as the modicum of perfection, we will end up in violent opposition.

Perhaps what Kevin Costner and crew is trying to convey is that the violence that comes about through the Hegelian dialectic can be avoided if we remember that we are not meant for this world. We are, as Gabriel Marcel points out, Homo Viator; we are “man on a journey.” When we define ourselves as such and remember that the journey is towards heaven, then we focus less on our grievances and enemies and more on our internal corruption, and the only violence needed is a violence of driving out our own ego.