The tale is told that as a yong boy, Maximilian Kolbe had a vision of the Mother of God, her arms extended toward him, holding two crowns, one white and the other red. Which crown would he choose?

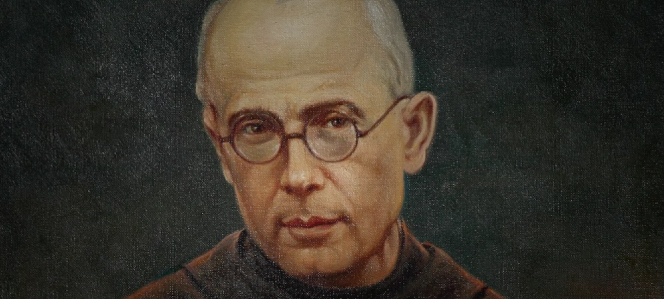

Such visions are not easily dismissed by those privileged to see such wonders, and so Maximilian dedicated his life to Christ, joining the Franciscan Order and later being ordained a priest.

Maximilian created an association called the Militia of Mary Immaculate,” which was dedicated to promote devotion to the Mother of God, and in doing so, bring others closer to Christ and his Church.

The movement grew, and Maximilian became a rather formidable and outspoken figure. In another time, this might have brought him fame, and maybe ecclesiastical advancement — but the time was World War II and Maximilian lived in Poland.

The Nazis arrested Maximilian in a purge of Poland’s clergy and intellectuals. He was sent to the deathcamp Auschwitz.

There he was stripped of any vestige of his former life. His Franciscan habit was taken away and Maximlian was given a prisoner’s striped uniform. To reinforce his indignity, he was made to wear the symbol of a pink triangle, which the Nazis used to identify prisoners who were homosexuals.

On July 30, 1941, in retaliation for the escape of a prisoner from the camp, ten men in Maximilians’s cellblock were chosen at random to be executed.

Maximilian, seeing that one of the prisoners had a wife and children, volunteered to take the man’s place. The Nazis were more than willing to accept his generosity.

Maximilian and the other men were stripped naked, locked in a basement cell and left to starve to death. Impatient that prisoners were not dying fast enough, Maximilian and the other remaining prisoners were killed by a lethal injection on August 14, 1941.

In 1982, Pope John Paul II declared Maximilian a saint, acclaiming him as a “martyr for charity.”

Christians, the century just past, the twentieth, was perhaps the bloodiest and most inhumane in all the many years of human civlization. We might note all the advancements, technological and otherwise, of this period, but what we became most skilled in was mass death.

We should not look back wistfully on the twentieth century, nor should we be uncritical about the so-called achievement of the modern world.

One of the lessons we might learn from all this is that what we call civilization is a rather thin veneer, and what lies beneath this surface is a terrifying heart of darkness. Christians, who are called to live in the truth, must be realists about this and cannot afford to be naive.

It was in the heart of civlized Europe, among the fading remains of Christian culture, that the death camps were built and millions of innocent men, women and children were put to death for no other reason than that their very existence challenged the ideological conceits of their oppressors.

In the midst of the world’s darkeness, we are called by our Baptism to be a light in the shadows of this fallen world. Saint Maximilian is one such light, his life and death stands as a testimony to Christ, the eternal light, whom the darkness cannot overcome.

For too many Christians, the faith is a safe routine, a kind of philosophy of self-improvement, something meant to be comfortable and comforting.

The witness of St. Maximilian stands against this illusion. Christian faith is not so much about safety as it is about risk. It is meant to take us out into the world, into the shadows, to be a light to show the way home to those who live in darkness.

May St. Maximilian intercede for us. May we imitate his selfless courage. May the fire of his holy light enkindle the embers of faith that may have grown cold in our own hearts.