When Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life hit movie theaters ten years ago today, the responses were either viscerally positive or viscerally negative. Some hailed it as an instant classic; others dismissed it as pretentious or indecipherable, with many people reportedly walking out of the theater mid-movie.

The critical response was mostly positive, but though it drew the Palme d’Or prize at Cannes, it still drew “boos” from scattered audience members when it premiered there and was panned by a handful of top critics. Audiences were even more divided: The Tree of Life still carries an unimpressive 60% audience rating at Rotten Tomatoes.

But the film’s divisiveness could very well have been an early sign of its greatness. Taxi Driver and Pulp Fiction also drew boos at Cannes, and Citizen Kane—now widely regarded as the greatest film ever made—had a very rocky start. As the decades roll along, the passion in both directions may just cool and converge into a single response: admiration.

One prominent advocate for the film was Roger Ebert. “Terrence Malick’s new film is a form of prayer,” he wrote in his initial review. “It created within me a spiritual awareness and made me more alert to the awe of existence.” A year before his passing, Ebert even included it in his list of the ten greatest films ever made. He was faced with having to replace Dekalog by Kieslowski because of a rules change. But what could stand alongside classics like Citizen Kane and Raging Bull? For Ebert, it was between two films of “almost foolhardy ambition”: Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York or The Tree of Life. Ebert chose the latter. “I believe it’s an important film,” he wrote, “and will only increase in stature over the years.” (As fate would have it, the last film Ebert would ever review was Malick’s next film: To the Wonder.)

I think Ebert was right to include it; it certainly tops my list. My experience watching this film on the big screen (which, should the opportunity arise, you should not miss) was transformative. Like Ebert, the film gave me a heightened alertness to the awe of being. Its Heideggerian meditativeness on why there is something rather than nothing, and just how beautiful and strange that something is, was a profound invitation to encounter the beauty and strangeness of God. What I experienced was not just a movie but a philosophical, spiritual, and even evangelical powerhouse of a work of art. (Indeed, The Tree of Life launched a “religious stage” of filmmaking for Malick, who is also busy working on The Way of the Wind about the life of Christ.)

But The Tree of Life is not simply an arthouse exercise in contemplation of the highest heights—it is also a poignant portrait of the smallest moments. It has the power to blow your mind but also to move you to tears. There simply is no other movie that better captures the whole depth and breadth of the human drama: the miracle of birth, the delicacy of infancy, the tensions of family, the magic of childhood, the connections of siblings, the shame of adolescence, the pressures of parenthood, the crises of middle age, the heartache of death; sin and grace, suffering and joy, fall and redemption, evil and goodness—all of it is there. But it also captures the holiness of the ordinary—the simplest actions overflowing with meaning. When I left the theater, the encounter with its beauty sent me; I was determined to share it, talk about it, write about it. It ended up being the very first thing I ever wrote about online, setting in motion a whole series of events that, quite literally, changed my life.

One of the most talked-about elements of the film is the twenty-minute “creation sequence,” a kind of masterpiece within the masterpiece that depicts the unfolding of the universe from the Big Bang, to planets, to life, and finally to human life. There is simply no other depiction of grandness of physical reality as visually stunning in the history of cinema. The only film that comes close is 2001: A Space Odyssey. But the entire movie—even when the focus is on the smallest things of reality instead of the biggest—is shot, in typical Malick style, with a careful eye for sumptuous and arresting beauty.

Part of what makes the creation sequence so powerful is its pairing with Zbigniew Presiner’s “Lacrimosa”—a striking example of Malick’s skillful use of music in the film. A beautiful original soundtrack by Alexandre Desplat is rounded out by over 30 songs. But of all the beautiful and often epic compositions—“Hymn to Dionysus” “My Country –Vltava (The Moldau),” “Les Barricades Mistérieuses,” “Funeral March,” “Agnus Dei”—John Tavener’s Orthodox-inspired “Funeral Canticle” stands out. It plays at the beginning and is repeated throughout like a refrain, and its English lyrics, which are difficult to make out, are of great significance in light of the story:

What earthy sweetness remaineth unmixed with grief?

What glory standeth immutable on earth?

All things are but shadows most feeble

But most deluding dreams

Various fascinating allusions also appear throughout the film. There are direct references to Scripture (“What I want to do, I can’t do,” the main character Jack whispers. “I do what I hate.” See Romans 7:15); Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (the “I dishonored it all, and didn’t notice the glory” and “Love everyone. Every leaf. Every ray of light” voiceover monologues closely mirror passages in the great Russian novel); and St. Augustine (the young Jack steals a neighbor’s nightgown, and in the extended version of the film, even steals and stomps on a neighbor’s vegetable plants, calling to mind the pear tree of the Confessions).

Despite the undeniable visual, musical, and literary brilliance, many people struggled with Malick’s experimental and more poetic approach to the narrative (an approach he pushed even further in several films after), which jumps between past and present, and voiceovers and on-screen (but often faint) dialogue. Even Sean Penn was displeased, remarking that “a clearer and more conventional narrative would have helped the film.”

But on a second viewing, the basic storyline becomes clearer. The film follows the O’Brien family—a father and mother (played by Brad Pitt and Jessica Chastain) and their three sons—jumping between three time periods: first, in the 60s, as the parents find out about the death of their middle son R.L. at nineteen; second, in the present, as the oldest son Jack (played by Sean Penn) finds himself, like Dante in the Inferno, lost in a kind of middle-aged spiritual desert on the anniversary of R.L.’s death; and finally, in the 50s, as the three boys grow up in Texas. This last section largely revolves around the coming-of-age arc of Jack, who struggles in his relationship with his parents, questions the world around him, and experiments with sin—small decisions that bring great violence and self-hatred into his soul. Criterion’s extended version of the film, which includes forty-nine minutes of footage (and which I just finally watched for the first time), adds even more detail to the plot, especially about the young Jack’s experiences.

Once you have these basic elements in place, the film’s inner logic and deeper themes open up, one of the most significant of which is the problem of evil and suffering (which Bishop Robert Barron hones in on in his excellent commentary). The film opens with an epigraph from the book of Job, which is also the focus of a homily about suffering later in the film, and at the heart of the story is the sorrow of R.L.’s death at a young age. Another important theme is a kind of sacramental awareness (underscored by a scene of baptism) of God’s presence and activity in and through the world—even the suffering itself.

So do those little poetic flourishes and touches that can be jarring and off-putting on first watch. One of the qualities of a great work is that you can return to it over and again, and every time you notice something new—an image, connection, or idea that you didn’t see before. The Tree of Life has this quality. There are fascinating little details that are easy to miss. For example, the final shot of the film of a bridge (the Verrazano Bridge in New York) is a symbol that, for a film packed with symbolic imagery, is no accident, perhaps calling to mind Christ as the bridge between man and God.

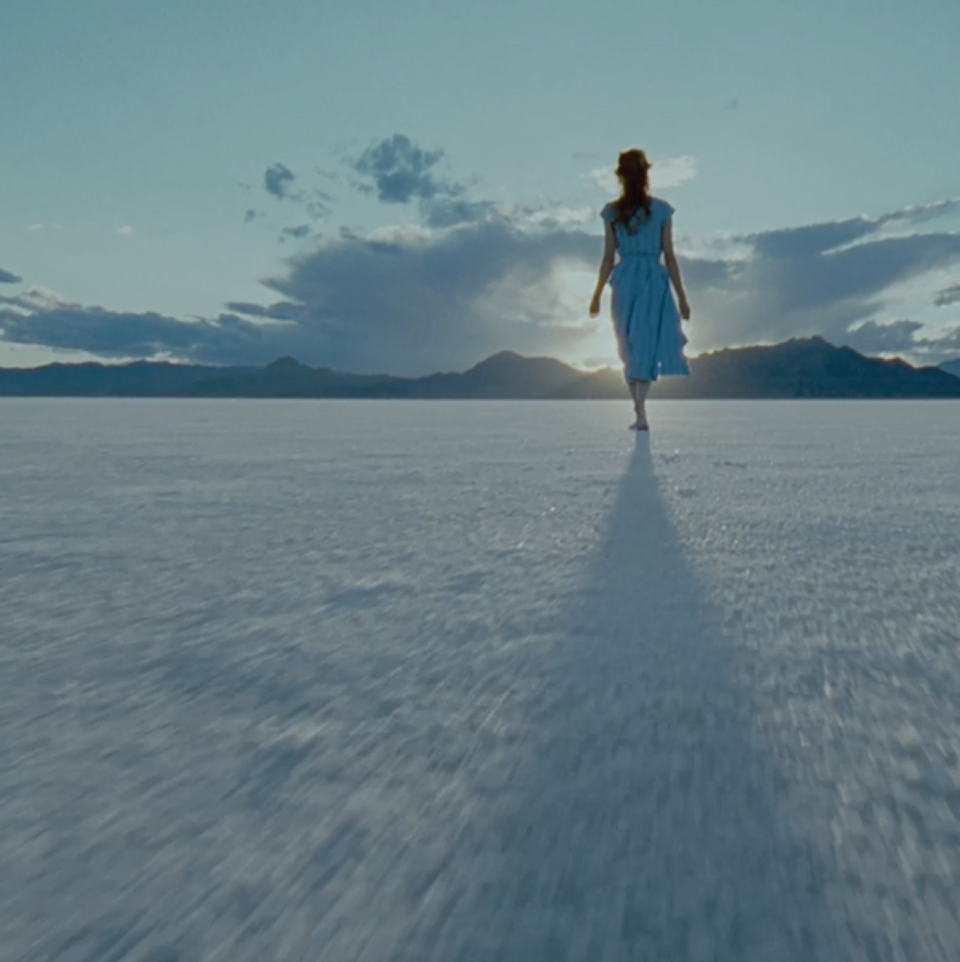

Then there is the young woman (listed only as “Guide” in the credits) who gently shepherds the O’Briens throughout the film. An interpretation I appreciated only after my brother pointed it out to me is that this is a Marian figure. This is especially clear in the final scene of the film where she guides Mrs. O’Brien’s hands in a kind of dance of surrender. “I give him to you,” Mrs. O’Brien whispers with the figure behind her. “I give you my son.” (Brett McCracken makes the case that she is an image of the Holy Spirit guiding the faithful—a reading that, especially given Mary’s role as the Spouse of the Spirit and her presence at the foot of the cross, there becoming the disciple’s mother, is not unrelated to my own.)

Characters also appear more subtle and complex, especially Mr. O’Brien (played by Brad Pitt). He’s a flawed man, to be sure, but a loving father. The common interpretation of him as representing “nature” and Chastain’s character as representing “grace”—the “two ways through life” laid out in the film’s opening scene—is an oversimplification insofar as it’s taken to mean that Mr. O’Brien is “bad,” evil, or sealed off from grace. Jack’s downward spiral into iniquity, after all, occurs while his father is away, and in the film’s climactic final scene, in which the O’Brien family is gathered together again, Mr. O’Brien is right there in the arms of his wife and children. Grace, in the Catholic perspective, perfects nature.

One of my favorite elements of the extended version was the fuller version of this final scene. Broadly understood to be the adult Jack’s vision of heaven, the imagery was ambiguous enough to be open to other interpretations. A vision of inner peace or transcendence perhaps? Of reconciliation with his family, or with his past? But the extended version, which shows other figures rising from the dead, leaves little doubt: this is a scene of resurrection. This brilliant film about the whole spectrum of human life embeds it all in the grandeur of its eternal destiny—known from the foundations of creation—in the new creation.

Was Roger Ebert right that The Tree of Life is an important film—and yes, one of the greatest—and will only increase in stature over the years? I believe he was. A decade later, it already has.