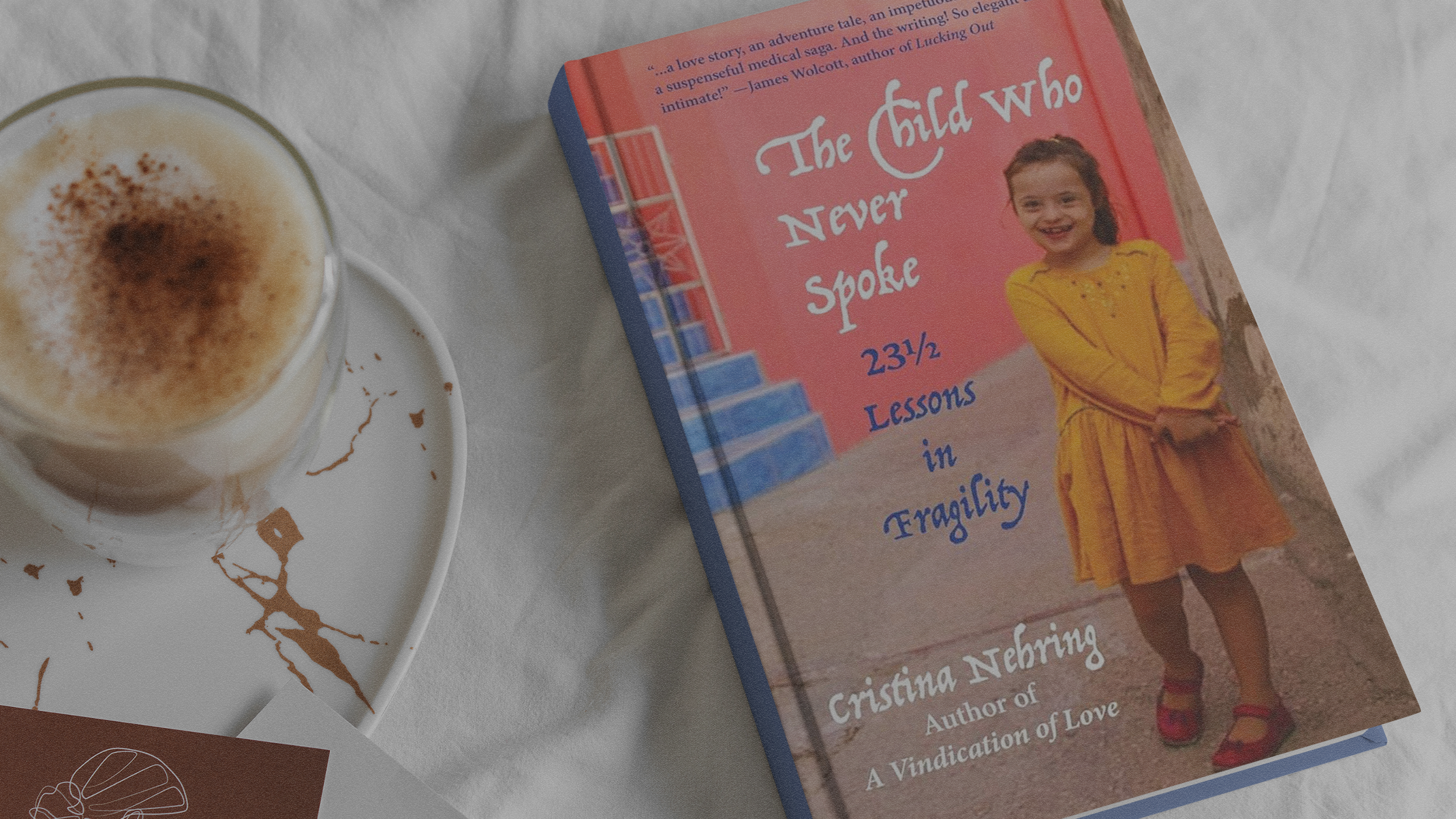

A new and different kind of book about Down syndrome was just published. It’s called The Child Who Never Spoke: 23 ½ Lessons in Fragility, and it was written by Cristina Nehring. You should read it. I say a “different” kind of book because it’s about much more than Down syndrome. It doesn’t follow the usual course of encouragement and admonition, nor does it simply rehearse all the positives and wonders of having a child with an extra 21st chromosome. All of that is here, but this book plunges far deeper. It is profoundly personal. I say it is more than a book about Down syndrome because it is really a story of the transformation that can happen simply by saying yes to life. It is a story about a single mother accepting challenges and uncertainty, and finding herself changed by giving herself completely to love.

As Catholics, we are all committed to the protection of innocent human life, but it is sometimes valuable to reach outside of our faith into the wilderness where decisions aren’t so cut and dried. Cristina Nehring isn’t a Catholic, nor, it seems, would she have ever considered herself a defender of life and motherhood. Quite the contrary. In her own words, she writes that she believed, “Becoming pregnant is an act of resignation. And just in case there’s a wee bit of hope for yourself remaining by the time you give birth, the next few years knock it out of you for good and real.” Her writing is sometimes edgy, but always honest.

Little did Nehring know how radically her perspective on life and motherhood would be changed by an unexpected pregnancy.

There is no poverty here, but the vindication of true love—the reward for a life given to another in total generosity of self.

In case you choose to read the book, and I hope you do, I don’t want to give too much away. Nehring has a PhD in English from UCLA and is an established author who has written for a variety of publications, including Condé Nast Traveler, The Atlantic, Harper’s, The American Scholar, and others. The front cover of this book says that Nehring is also the author of a book titled A Vindication of Love. I looked it up and found a review in Slate. Toward the beginning of the review, in reflecting on the idea of equitable marriage, the example given is former President Barack Obama and his wife former First Lady Michelle Obama and their “studiously scheduled outings” together:

To Cristina Nehring, author of the ambitious polemic A Vindication of Love: Reclaiming Romance for the Twenty-First Century, one suspects, it [equitable marriage] would represent all that is wrong with marriage today.

Nehring yearns for a revival of a messier ardor. In her view, we have domesticated love past all recognition, turning what is rightly leonine, destructive, and majestic into a yawning, chubby house cat. Hers is no modest project. She wants nothing less than to radicalize our framework for love, mainly by restoring its chaotic potential: ‘Romance in our day is a poor and shrunken thing,’ she writes. ‘Among the many rights we must reclaim in love is the right to fail.’

A Vindication of Love was published in 2009. Her daughter, Eurydice, was born in 2008. Nehring’s lessons in love became messy very quickly.

English is an impoverished language in so many ways. We love puppies, ice cream, God, our spouses, and our children all with the same word: “love.” Of course, those feelings and those relationships couldn’t be more different, but in the times we live in, “love” is fickle, temporary, or a toy, and almost always poorly understood. In our uncommitted and superficial world, Westerners, and maybe the rest of the world too, are hung up on the emotions that relate our “loves” to what the Greeks called eros—not phileo, and certainly not agape.

Nehring’s daughter, Eurydice (meaning “wide justice”), bears a Greek name, I suppose, because she was conceived on the Island of Crete in a mismatched, passionate relationship that proved too problematic to endure. After spending the night with the man who would become Eurydice’s father, Nehring writes that when she saw him in the morning, she “gingerly” said, “Agapi mu, ‘My Love.’” If he shared the same depth of love for her, it rested on very insubstantial ground. The relationship crumbled, and she decided to have an abortion. Nehring returned to her family home in Los Angeles looking for support where a psychologist and all those around her encouraged the same. But Cristina Nehring was stubborn. A couple of months out from delivery, she returned to her adopted home in Paris where she delivered her surprise gift of a little girl with Down syndrome, and where the two remain today as closely united as any mother and child could be.

The years from Eurydice’s birth that lead up to the publication of this book, The Child Who Never Spoke, would prove to be Nehring’s true vindication of love. In 23 ½ Lessons, the experiences she recounts read like fiction, but there is plenty of evidence to validate them in fact.

This beautiful book is an adventure story, a story that teeters between life and death on two continents, a travelogue, a book of wisdom, and most of all—a story of how a mother’s love is a crash course in agape—the love that mirrors the divine love. In an age where many receive a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome, or some other disability, and reject it, Nehring’s stubbornness caused her to say yes to life—not as a Catholic, and I would guess not even as a practicing Christian. In doing so, she became the single mother of a little girl who would change her life and open her heart to the deepest love she had ever known.

Nehring admits to being a nomad, an untetherable romantic, and a most unlikely mother—in fact, one who from her earliest years never ever wanted to play with a baby doll, much less submit to a life “hindered” by a child. What she discovered in saying no to abortion was not a negation of self but the discovery of her highest purpose in motherhood and in a love that surpasses reason. The book reflects on two lives shuttled between Los Angeles and Paris and then destinations far and wide. The conception resulting from eros inspires the deepest sacrificial love between this mother and her special child. They became one—travel companions and adventurers facing life’s challenges and a few dangers—never apart.

One of my favorite verities Nehring expresses in this beautiful book is the sentence, “We only know how much we can do when it is demanded of us that we do it.” Those who commit their lives to safety, who reject children through contraception or abort them after a prenatal diagnosis or manufacture them via IVF according to their own genetic specifications, live in a hermetic poverty of self-knowledge and a rejection of grace.

There is no poverty here, but the vindication of true love—the reward for a life given to another in total generosity of self. That is a lesson I am so grateful to have been reminded of by The Child Who Never Spoke. That is the lesson we are all reminded of every time we gaze at the crucified Lord on the cross.