There was once a time when morally serious people used morally serious words—words like “freedom,” “equality,” “justice,” and “goodness”—to engage in morally serious debate, a debate that was premised on the shared belief that objective truth was possible, if painfully complex, to identify and abide by. But then came the liberators—that’s what they called themselves, though they had other designs in mind—who began announcing, first from university lecture halls, then in public squares, and eventually in boardrooms, that these “values” were nothing more than the machinations of hate-filled, power-ravenous religious men whose only desire was to control the minds and bodies of the people by preventing them from being their true selves. That message, it turns out, sold itself, and so the people turned their backs on those once-hallowed words, setting off in pursuit of money and pleasure, especially sexual pleasure, all expediently redefined as “their dreams.”

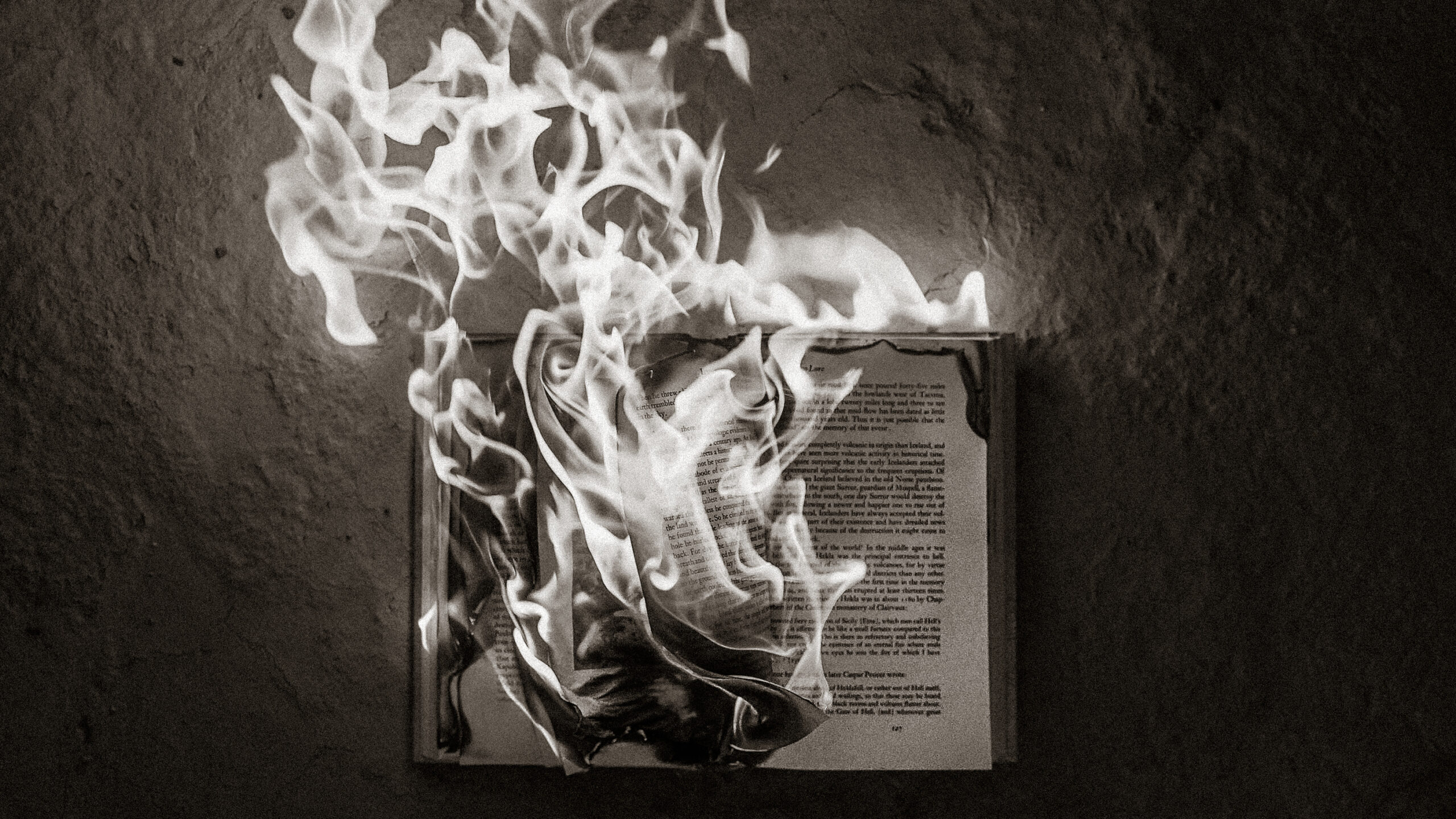

The liberators, however, were shrewd; they knew that those words, still preserved in the books of old, remained a threat to their goals. And they understood that, though necessary, it wouldn’t be enough simply to destroy the old books by sprinkling them with ideological poison (“These are the tools of your oppressors, dear ones. Stay away!”). There would also need to be new books, books that not only contained new words—words like “heteronormativity” and “cisgendered” and “anti-racism” and “cultural appropriation”—but also books (and this is the twist of devilish genius) that had all the old words, as well, but now with entirely new meanings.

All they want is equality over you. All they want is justice . . .

And so the liberators went to work, gutting and stuffing, gutting and stuffing, gutting and stuffing. From now on “freedom” would no longer mean the liberty to act in accordance with the true, the good, and the beautiful; it would mean doing whatever you want provided others say “yes” (and if they can’t say “yes” because of age or infirmity, not to worry: they’re not real people anyway, so do as you will). “Equality” would no longer mean regarding all people as moral equals because of their inherent dignity; it would mean treating some as less valuable than others, not based on character, but rather on what they look like and what they believe. “Justice” would no longer mean giving everyone her or his due according to their actions; it would mean raw redistribution, taking from the wrong people and giving it to the right ones. And goodness: goodness would no longer mean conforming to moral reality, pursuing the health of the soul which is just as real as the health of the body; it would mean participating in insatiable revolution, rising up and tearing down for the purpose of rising and tearing again.

The people seemed happy and thanked their liberators by giving them the places of power and prestige in their communities. A few missed the old meaning of the words and were suspicious of the new order, but most were content to let the past go.

One day, however, moral calamities started befalling some of the people: barbarian hordes began appearing from the dark, catching their victims by surprise, distracted, as they were, by their gadgets. The hordes torched their businesses, stripped them of their jobs, poisoned their children’s minds and bodies, and even wantonly murdered the defenseless, young and old, on the streets and in their own homes. Some resisted, but the hordes were too big, too powerful, to be repelled by the victims alone, and so they turned to their neighbors for help. “See what has been done!” they cried. “It is unjust. Join us in standing up to this evil!”

But to their horror, many were silent, pretending they did not see what they saw. And the rest, confused and agitated by the tumult, responded using the words their ancestors knew by heart but that had now lost their primordial meaning: “This is all your fault,” they seethed. “It is you who are disturbing the peace. If you wouldn’t have been standing there, the hordes never would have to have pushed you out of the way; if you hadn’t owned all those things, the hordes wouldn’t have to have taken them from you; and if you hadn’t existed in the first place, then they wouldn’t have to have killed you. All they want is the freedom to be who they are. All they want is equality over you. All they want is justice. Don’t you see—they are the victims, and you the aggressors. They are the good ones, and you are the bad ones.”

Panicking, those under attack looked for any sign among the silent that they recognized this to be the rantings of madmen and -women, that it could not possibly be true that mayhem was not only being permitted but celebrated. But it was too late. The hordes and the people had gradually—and then very suddenly—become one. The oppressors and the oppressed? One. The thief and the victim? One. The freedom fighter and the terrorist? One. The arsonist and the fireman? One. The scapegoat and the raving crowds in vicious pursuit? All one, all self-righteous combatants in a war of all against all.

The plan had worked: in the name of freedom, the liberators had seduced the people into slavery; in the name of equality, the liberators had inspired the people to fashion elaborate caste systems; in the name of justice, the liberators cheered as the people tormented their neighbors; and in the name of goodness, the liberators flashed a dark grin as the people clawed at one another to see who among them could bow most obsequiously to evil.