For my Mom’s 60th birthday, I put together a tribute video complete with creased photographs, old music, and clips of my brothers recounting a favorite memory of her—mostly revolving around her cooking or buying the four of us food.

As part of the tribute, I asked my Dad to summarize their forty years of marriage together in a minute-long clip—a Herculean task that he met with such calmness and profundity that I knew instantly it would be the grand finale. I also knew this important clip needed an equally important song in the background. But which one?

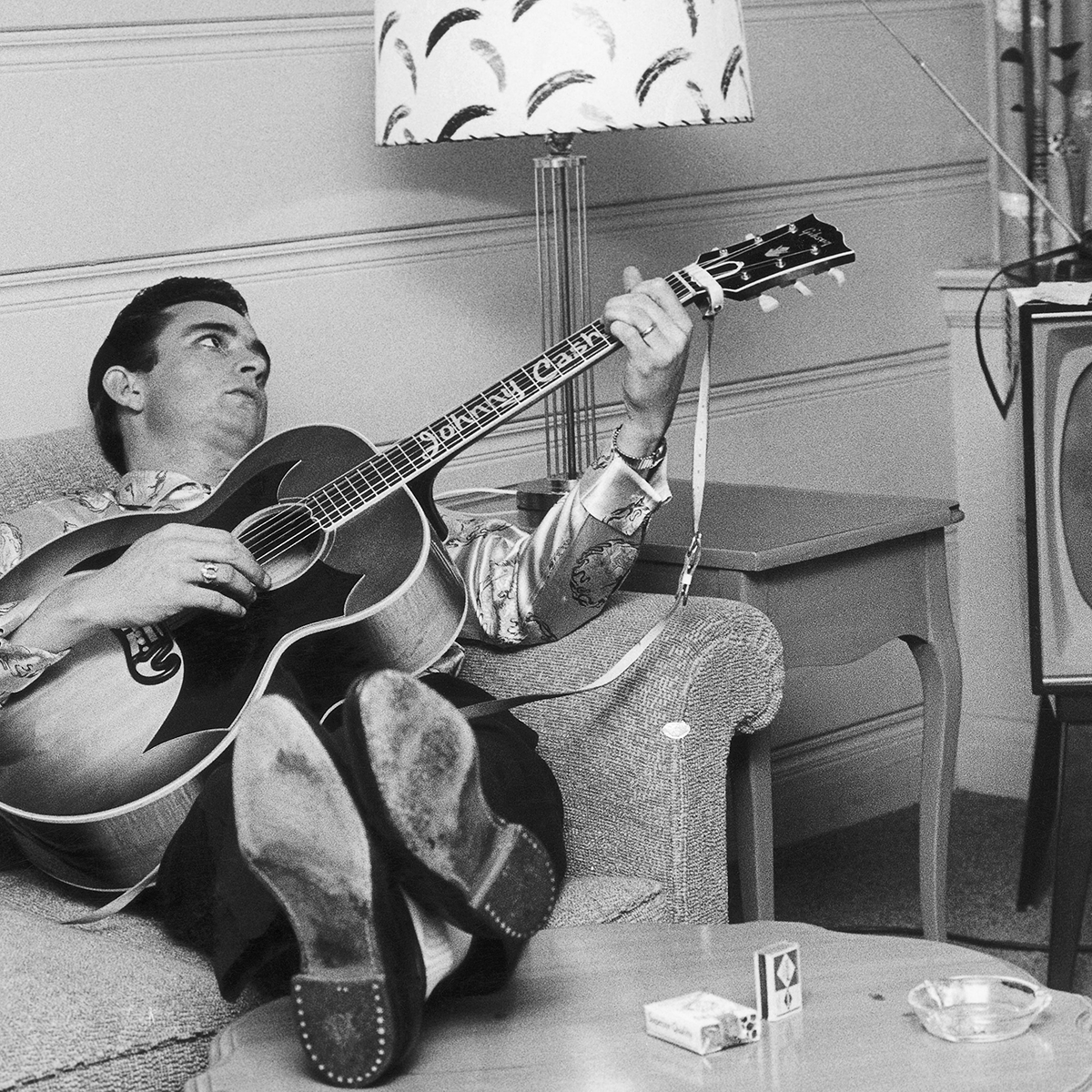

I finally decided on Johnny Cash’s cover of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” from American IV, the last album released before his death in 2003—just four months after his wife June Carter’s death.

When we debuted the video, I fully expected there to not be a dry eye in the room—and sure enough, there wasn’t.

But what I didn’t expect was that every time I returned to the song, I felt that same ineffable emotion welling up inside of me. For a man who prides himself on a certain flinty philosophical temperament, this song had become a rare piece of emotional kryptonite. By the second verse—sometimes even before the first word—I was tearing up. Even trying (and failing) to explain why it moved me so much primed the waterworks.

Throughout his career, Johnny Cash cranked out some truly powerful songs about murder, prison, and despair, the kind of songs that made him so beloved among both believers and non-believers. (One of my favorite scenes in Walk the Line shows a record company executive chastising Cash: “Your fans are gospel folk, Johnny. They’re Christians, and they don’t wanna hear you singing to a bunch of murderers and rapists, tryin’ to cheer ’em up.” The man in black responds without missing a beat: “Then they ain’t Christians.”) And with Rick Rubin at the boards, standing at death’s door, his voice never sounded so wise, clear, and urgent. I never walked away from a track like “Hurt” (a cover of Nine Inch Nails) unscathed.

But this song was something else entirely—it was devastating.

My wife asked me if I thought about my parents’ marriage when I heard the song, and I admitted that I did. But I confessed that I also thought about seeing her for the first time in English class in college; about finally meeting our first baby face to face any day now; about the 70-year old Cash singing to the love of his life June Carter just months before they both passed on; about my 90-year-old grandma visiting her catatonic husband day in and day out for over a decade in the nursing home. I thought about all of these at once, but not really any of them.

I realized that it wasn’t any one particular example of love that came to mind, but agape love itself—a love that was bigger than any one person’s love for something or someone, yet still animating each and every of its instantiations. Johnny Cash’s words and voice were so devoid of pretense, so filled with self-giving; this song was bigger than me and my thoughts, bigger than that man and his music. It was beautiful.

There is a kind of supra-rational argument to be made for God through this kind of musical experience. I would use Peter Kreeft’s same formulation for the argument from Aesthetic Experience to articulate the argument from Johnny Cash:

a) There is the music of Johnny Cash.

b) Therefore, there must be a God.

There are many compelling arguments for God’s existence: arguments from first cause, cosmology, morality, contemporary physics, even evolutionary history. Seen in this context, the argument from beauty seems to lose quite a bit of its power. After all, it’s not a formal argument, and more of an appeal to personal experience. But isn’t personal experience just that—personal? How could anyone formulate an objective proof based on a poetic “deepity” experienced subjectively?

In the end, I agree that this “argument” should only be seen in light of other, more objective intellectual arguments for God’s existence—after all, we have reason, and should exercise our reason fully—but neither should it be dismissed as inadmissible evidence. Given that we are all persons living in and coping with the world, a life-changing experience is not exactly data we can turn our nose up at when it comes to the most important of questions. In fact, for many lives, it is often the case that a personal experience seems to tip the scales of belief and unbelief.

It’s worth noting that part of Christian apologist and philosopher William Lane Craig’s debate routine is to follow up formal arguments for God’s existence with an informal argument from personal experience.

“This isn’t really an argument for God’s existence; rather it’s the claim that you can know God exists wholly apart from arguments, by personally experiencing him. . . . In the experiential context of seeing and feeling and hearing things, I naturally form the belief that there are certain physical objects which I am sensing. Thus, my basic beliefs are not arbitrary, but appropriately grounded in experience. There may be no way to prove such beliefs, and yet it’s perfectly rational to hold them. Such beliefs are thus not merely basic, but properly basic. In the same way, belief in God is for those who seek Him a properly basic belief grounded in their experience of God.”

The atheist might instantly retort: one man’s Bach is another man’s din; one man’s beauty is another man’s bedlam; and one man’s personal experience of God is another man’s delusion!

But then, the argument isn’t about aesthetics and the objectivity of taste but the universality of beauty in human life, a phenomenon which atheist Christopher Hitchens described as well as anyone:

“The sense that there’s something beyond the material—or, if not beyond it, not entirely consistent materially with it, is I think a very important matter. What you could call the numinous, or the transcendent, or at its best I suppose the ecstatic. . . . We know what we mean by it when we think about certain kinds of music perhaps; certainly the relationship, or the coincidence but sometimes very powerful, between music and love. . .”

In the end, the argument from Johnny Cash is not about this one song about love—it could be any song, about anything. It could be a painting, a person, a place, or even a childhood memory like the one described by C.S. Lewis in Surprised by Joy: “Once in those early days my brother brought into the nursery the lid of a biscuit tin which he had covered with moss and garnished with twigs and flowers so as to make it a garden or a toy forest. This was the first beauty I ever knew. . . . As long as I live my imagination of Paradise will retain something of my brother’s toy garden.”

Beauty, wherever it appears to you, is yours for the taking—and it tends to speak for itself. It opens us to paradise like a flower opens to the sun. Some of us say that this glimpse of heaven is false; that just as “love” is nothing more than a chemical cocktail concocted by the brain, the “mystical” experience of beauty—regardless of how overwhelming and significant it may seem from any particular subject’s vantage point—is reducible to electrochemical signals in that brain. We stand stalwart, refusing to give an inch to the immaterial, and we protest too much. These towering waves of beauty continually assail us throughout our lives, seizing and saturating our cool objectification and pointing beyond themselves and our sight.

Because beauty, others say, is a way. . .

This piece was originally published on August 24, 2015 in the Word on Fire Blog.