Everyone who loves The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings knows that the initials JRRT stand for John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. What is less well known is that he also bore the name Philip. We can see this in a note that Tolkien wrote in 1931. In Elvish script, he gives his name as “John Ronald Philip Reuel.”1 Where did Philip come from?

Tolkien was a Catholic. He had been baptized into the Anglican Church as an infant at the Anglican Cathedral of St. Andrew and St. Michael in Bloemfontein, South Africa, but as an eleven-year old boy, he followed his mother Mabel into the Catholic faith. He was received at Christmas 1903 when he took his first Holy Communion.2

When a convert is received into the Catholic Church, or when a cradle Catholic receives the sacrament of confirmation, they often take on the name of a saint to whom they feel some special sort of connection. Thus, the fantasy writer George R.R. Martin, who was raised Catholic, was born George Raymond Martin, adding the name ‘Richard’ when he was confirmed at age 13.3

Taking on a saint’s name is not just an indication of one’s interest in or admiration for a particular Catholic figure from the past. It goes with a belief in ‘the communion of saints.’ This communion is a bit like the ethos or spirit of a family, where brothers, sisters, uncles, aunts, and cousins all have something in common. What Catholics have in common is that they all worship God their Father and Christ their Brother, and they honor Mary as their mother, for Catholics understand Jesus’s words to the beloved disciple John (“Behold your mother,” John 19:27) as applying to them too by a kind of spiritual inheritance.

A saint is someone who has died in friendship with God and, having been perfected in sanctity through that cleaning-up process called purgatory, has entered the presence of God in Heaven (Rev. 21:27; 1 Cor. 3:15). Just as individual people have particular friendships on earth, so too Catholics typically have certain ‘spiritual friends’: saints to whom they feel a particular connection or affinity, like your favorite cousin or that great-aunt of whom you’re especially fond. In Tolkien’s invented world of Middle-earth, he depicts something a little like this through the Valar, angelic spirits whom people may call on—so he explains—“as a Catholic might on a Saint.”4

There were a number of saints who were important to Tolkien in one way or another, whether as spiritual intercessors or as models of faith. The most significant of these was St. Philip Neri, the founder of the Oratorians. It is to Philip Neri that Tolkien was referring when he wrote his name in Elvish as “John Ronald Philip Reuel.” I was able to check this in 2020 with Tolkien’s daughter, Priscilla, who confirmed my suspicion.5

But who was St. Philip Neri, and what would have prompted Tolkien to choose him as his particular patron?

It was at the Birmingham Oratory that Tolkien spent his childhood and youth, and it was one of the Oratorian Fathers, Fr. Francis Morgan, who was Tolkien’s guardian after his mother died, and who became a close family friend in later years. The Oratory in Birmingham was the first to be established in England, and it was personally founded by none other than John Henry Newman, who was its Superior until his death in 1890. It is still going strong today, one of over seventy Oratories world-wide.

The Congregation of the Oratory itself was established in the sixteenth century by St. Philip Neri, who, despite having very little name-recognition in the wider world, is a major figure in Church history—he is known as the ‘third apostle of Rome’, coming in only after St. Peter and St. Paul, because he did so much to restore the reputation of Rome during a period in which it had become decadent and morally corrupt.

Born in 1515 in Florence, Italy, Philip came to Rome as a young man, where he was ordained a priest and gathered around himself a company of other men, all seeking holiness of life. The Rome of his day was in a bad way, but by his remarkable character and personal example, Philip had a considerable and long-lasting reforming effect on the Catholic clergy and laity of ‘the eternal city’; he was declared a saint only a few years after his death in 1595.

Eventually, a community formed from the young men who were drawn to Philip’s approach to prayer and the Christian life, and was formally recognized as the Congregation of the Oratory by the Pope in 1575. New Oratories were founded, in Italy and beyond.

St. Philip Neri, as well as being “the third apostle of Rome” is the “apostle of joy”. He was by all accounts a cheerful and joyful man, who frequently played jokes on his friends—though usually with an underlying purpose: to encourage the development of humility and self-forgetfulness. What Philip offered to his spiritual children—and the Oratorian Fathers referred to themselves as the ‘sons of St. Philip’—was an emphasis on a light-hearted spirit, even when (indeed especially when) confronting the most serious of issues. Philip himself had no easy time of it, as he experienced repeated setbacks and rejections in his lifelong work to renew the moral life of Rome.

As a boy, Tolkien had few enough reasons to be light-hearted. His mother had died, as he recalled many years later, “worn out with persecution, poverty, and largely consequent, disease, in the effort to hand on to us small boys [Tolkien himself and his younger brother, Hilary] the Faith.”6 Her diabetes was incurable at the time (since insulin treatment was only begun in the 1920s), but family support—financial and personal—might well have helped extend her life—and certainly would have made the last years less lonely and painful. Tolkien was more familiar with bereavement, anxiety, bitterness, and resentment than with joy. But in the fellowship of the Oratory, he was able gradually to relax and enjoy his boyhood, despite the pain of his loss and the uncertainty of his future.

Oratorian spirituality also places a strong emphasis on the sacrament of reconciliation (confession). As a boy, Tolkien had much that he would have had to wrestle with regarding forgiveness. Not only had his extended family rejected his mother, but even her memory had been treated disrespectfully, as their aunt Beatrice Suffield, who had taken the boys in, briefly, had destroyed Mabel’s letters on her own initiative—the sort of action that could easily have felt utterly unforgivable. Possibly Tolkien had quite natural impulses of resentment toward his mother and toward the Church—for after all, had she not become a Catholic, things would have been very different.

He wrote later that he “first learned charity and forgiveness”7 from Fr. Francis, and this message would have been affirmed by the overall approach at the Oratory. The Oratorian approach to confession is not punitive or shaming, but rather places it in the context of love and reconciliation. There’s no reason to assume that Fr. Francis heard Tolkien’s confessions himself; indeed, given that Fr. Francis was Tolkien’s guardian, it’s probable that he did not. It would have allowed more personal space and privacy for him to make his confessions to other Fathers of the Oratory.

It is remarkable, given the circumstances, that Tolkien was able to develop a genuinely close relationship with parts of his extended family, and to do so relatively soon after his mother’s death. Fr. Francis would have been watchful that the family did not try to undermine the faith of the boys to whom he was guardian. It would have been simpler and easier for Fr. Francis to have isolated Tolkien from his extended family, writing them off entirely; easier perhaps, emotionally, for young Ronald to have written them off himself. But instead, Fr. Francis ensured that Tolkien spent school holidays with relatives on both his father’s and mother’s sides, the Tolkien, Mitton, and Incledon families. These interactions were an embodiment of ‘charity and forgiveness,’ a demonstration in action that Tolkien had forgiven (or was endeavoring to forgive) his relatives for the role that he believed they might have played in his mother’s suffering and death.

Not many years later, Tolkien would go through the horrors and losses of the Great War. These experiences would be more than enough to account for a bleak view of life, and indeed Tolkien had a depressive streak in his character. What is surprising is not that he had a pessimistic side, but that he also had such a deep-seated streak of joy and fun We can see this aspect of Tolkien’s personality reflected in his most famous creation, the Hobbits, a people who are by nature merry and full of laughter, “fond of cheerful jests at all times”; they are “hospitable, and delighted in parties.”8 Indeed, he once remarked, “I am in fact a Hobbit (in all but size).”9 Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings take the characters, and the reader, through darkness, sorrow, and loss, but both stories are also deeply grounded in the simple, joyful life of the Hobbits in the Shire—where both books begin, and end.

High spirits are not surprising in boys, even orphaned ones, but Tolkien’s willingness to be playful, even silly, as an adult and as a serious Oxford professor is less usual. What enabled Tolkien to integrate this joyfulness into his complex adult personality, despite the sorrows of his childhood and youth? A good case can be made that the spirituality of St. Philip Neri helped him to do so.

By taking Philip’s name at his confirmation in the Church, Tolkien chose him as his particular patron in the spiritual life. In most cases the saint’s name is not used publicly, but it is nevertheless considered to be a genuine part of one’s own name, which explains why Tolkien, in Elvish script, should have declared himself to be “John Ronald Philip Reuel.”

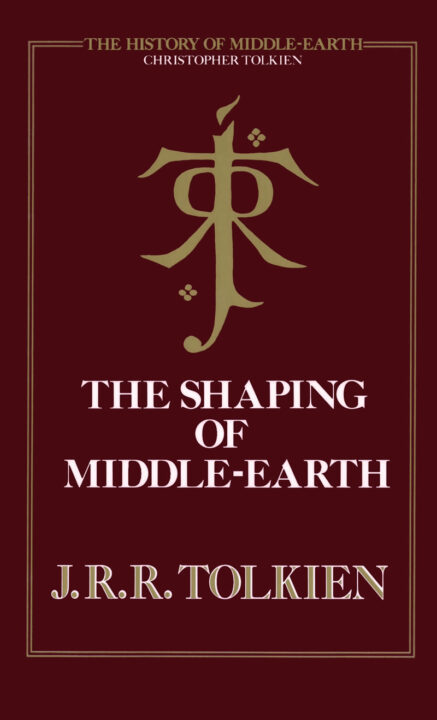

It may also explain, I think, an odd detail in the famous monogram of Tolkien’s initials, the monogram which is often found on the front cover or the title-page of Tolkien’s books, where the letters are somewhat superimposed on one another and loop in and out of one another.

Looking carefully at this monogram, it is easy to recognize the T for Tolkien and the J for John, with the mirror-image Rs (Ronald Reuel) on either side; but I think that the P is also there, almost hidden.

One can trace the P as sharing the loop of the right-hand R and the vertical line of the T. So far, so invisible! The presence of the P is made visible, I believe, by the otherwise apparently extraneous spur on the right-hand side of the T upright. This little spur or foot appears on only one side, the right side, so it can’t be part of the feet of the mirror-image Rs nor part of the base of the T, where the feet or the base would emerge equally on both sides of the upright. It is an asymmetrical element in an otherwise highly symmetrical and balanced image.

Tolkien used various versions of this monogram throughout his life, as an artistic signature. The version we see on his books today has been slightly touched-up by a professional graphic-designer employed by the publisher, but is almost identical to Tolkien’s carefully hand-drawn versions.10 Given the careful oversight of Tolkien’s literary estate by his son Christopher, we can be sure that the published version represents his father’s intentions.

Once we are aware that Tolkien had the name Philip, chosen for his confirmation saint Philip Neri, this asymmetry makes better sense: the little right-hand spur is meant to indicate the foot of the P. If this reading of his monogram is correct, it could even be considered a sort of visual pun or homage to St. Philip, who placed such emphasis on humility and hiddenness and humour.11

The monogram presents us, I would venture to suggest, with not four intertwined letters, but five—the five initials of a man who believed in the communion of saints, was raised by an Oratorian guardian, and had a special devotion to the apostle of joy: John Ronald Philip Reuel Tolkien.

This article was originally published on May 26, 2023 on Evangelization & Culture Online and draws on material from Holly Ordway’s book, Tolkien’s Faith: A Spiritual Biography (Word on Fire Academic, 2023).

1 J.R.R. Tolkien, The Qenya Alphabet. Edited with introduction and commentary by Arden R. Smith. In Parma Eldalameron 20, 77.

2 Humphrey Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, 36; Christina Scull and Wayne G. Hammond, The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide: Chronology, 10.

3 George R.R. Martin, NPR interview, April 28, 2011.

4 J.R.R. Tolkien, Letters, 193n.

5 Personal communication with Priscilla Tolkien, Oxford, 2 October 2020.

6 Letters, 353-354.

7 Letters, 354.

8 J.R.R. Tolkien, preface to The Lord of the Rings.

9 Letters, 288.

10 J.R.R. Tolkien, The Art of The Hobbit, ed. Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull, 138, 104.

11 For more on Tolkien’s interest in hiddenness, see Michael Ward’s “Peak Middle-earth: Why Mount Doom is not the Climax of The Lord of the Rings.”