“The Beauty of Creation Beckons: The Secret Garden & the Awakening to Abundant Life“ was originally published in the Summer 2022 Childhood issue of Evangelization & Culture, the Word on Fire Institute‘s quarterly journal. To learn more and discover more pieces like this, start your membership today.

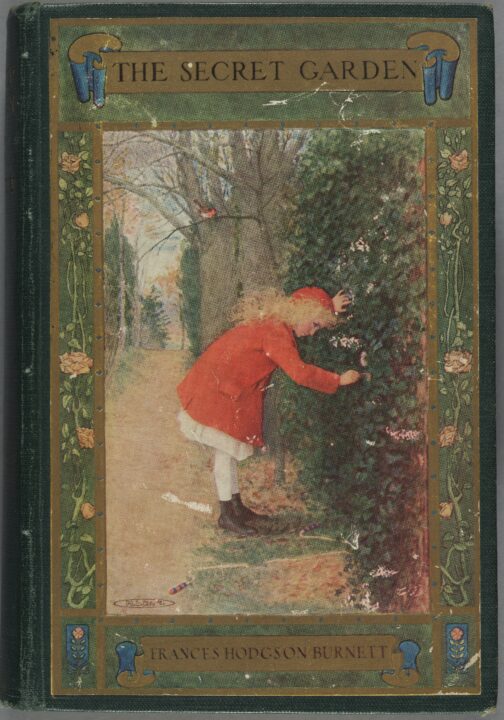

“No book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally (and often far more) worth reading at the age of fifty,” twentieth-century apologist C.S. Lewis claimed. I heartily agree. There are many worthwhile children’s tales that are even more wonderful when we re-encounter them as adults, and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden is such a one. Many beloved classics follow the coming-of-age formula of a young protagonist embarking on the adventure of adulthood (think Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ The Yearling or Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women), but The Secret Garden is the only classic story I can think of that is an anti-coming-of-age tale. The challenge its characters face is not leaving childhood behind but discovering it. In Burnett’s novel, the young characters awaken from cynicism to childlike joy. More than just a heartwarming story, The Secret Garden illuminates how beauty can evangelize us. It is a compelling answer to the claims of modernism that deny that God speaks to us through his creation.

Burnett’s story begins in India, where a cholera outbreak orphans young Mary Lennox. Unpleasant and spoiled as a consequence of her frivolous parents who ignored her existence and left her care to servants, Mary is shipped to England after their deaths to live at her widower uncle’s estate on the wild moors of Yorkshire. With her uncle on an extended trip overseas, Mary is again left alone and is tyrannical, rude, and miserable. She has never been cared for by a loving guardian, enjoyed the friendship of other children, or learned to joke or play. She has never learned how to be a child at all. But due to overwhelming boredom, she is pushed by a kind maid named Martha Sowerby to the outdoors to entertain herself in the gardens of Misselthwaite Manor. The chilly air of the moor, the scent of the soil, and the warmth of the sun begin to awaken in Mary an interest in life. She begins to delight in the natural world, and the idea of having a garden of her own starts to ease the malaise afflicting her. As bulbs stir beneath the soil, Mary “was becoming wider awake every day which passed at Misselthwaite.”

The Secret Garden speaks to how God evangelizes us through the works of his hands . . .

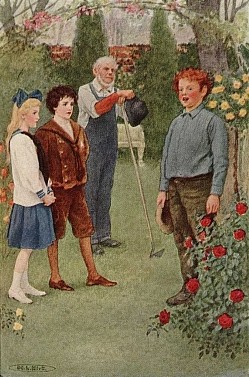

As Mary begins to fall in love with nature, she also experiences a surprising new feeling toward God’s human creatures: affection. Having never cared for a soul, she is startled to find that she likes Martha, the maid, as well as Misselthwaite’s aged and grumpy gardener, Ben Weatherstaff, and the friendly robin that follows him about his work. And by reputation, Mary likes Martha’s brother, Dickon, and mother, Susan, and is eager to meet them. When Mary needs help resurrecting a neglected and secret walled garden, she seeks out Dickon’s help and her first friendship blooms. While “Mary, Mary, quite contrary” often acts like a sour old woman, cynical and cold, Dickon Sowerby is the opposite. He is like a fairy prince of childhood. He is full of warmth and life, and wild animals befriend and follow him as if he has them under a magic spell. In Mary’s words, “He’s always looking up in the sky to watch birds flying—or looking down at the earth to see something growing. He has such round blue eyes and they are so wide open with looking about. And he laughs such a big laugh with his wide mouth—and his cheeks are as red—as red as cherries.” Dickon roams the moor in joyous wonder. By virtue of simply being himself, he calls Mary to view the world around her with childlike awe, as he does.

The glory of the garden and of friendship has a physical effect on Mary. She gains weight and color, as playing in the garden makes her strong and hardy, and thus cultivates a new interest in her meals. But the enchantment of the garden doesn’t just change Mary; it equips her to awaken others. Mary discovers her ten-year-old cousin, Colin, who is an invalid, isolating himself in one room of the vast manor house, never leaving his bed. Born just as his mother died after an accidental fall in the walled garden, he has been avoided by his grieving father and left to tyrannize the staff. Newly invigorated by the garden (and by Mary and Dickon), Colin stands for the first time on his own, begins to walk, and then runs. But Mary and Colin’s inner transformations are just as significant as reclaiming their physical health. The formerly somber and selfish creatures learn to play, skip, work the earth, revel in flowers, and love other people. They are healed inside and out in their beloved garden, which is a symbol of the children themselves—a place full of potential just under the surface despite years of neglect by those who should have tended to it.

. . . when we embrace an attitude of childlike wonder and gratitude, we become evangelizers ourselves.

While the children have instinctual desires for what is good, their guardians have never cultivated their young souls. Burnett reveals a glimmer of Mary’s natural desire for participation in the beauty of God’s creation long before she comes to Misselthwaite and is truly introduced to the joy of gardening. Back in India before her parents’ deaths, she would amuse herself by “planting” cut hibiscus flowers in the earth; they then wilted and died in the sun. Without any guidance or nurturing, Mary, like the doomed flower cuttings, could not bear fruit. But despite the great failures of Mary’s and Colin’s parents, there is someone working for their welfare behind the scenes: Martha and Dickon’s mother, Susan Sowerby. Although Mary and Colin do not meet her until the very end of the story, they are fascinated by every description of this hard-working, practical, selfless woman who is quite different from Mary’s narcissistic late parents and Colin’s absent father, Mr. Craven. Mrs. Sowerby embodies maternal warmth and is concerned about not only her family but any child in need of a mother’s care. Well-respected for her wisdom and skill at raising children on a shoestring budget, she is interested in Mary and Colin as soon as she knows of their existence and advises Mr. Craven about what children need to thrive.

Mrs. Sowerby’s simple motherly love is an invisible force that drives the plot and shows the children that the world is full of goodness, truth, and beauty that points them to God. The children are full of wonder, but initially, they lack the language to express the goodness of God’s creation and their own transformation. They call it “magic,” although they do not yet know the “magician” behind it. Colin explains, “I keep saying to myself, ‘What is it? What is it?’ It’s something. It can’t be nothing! I don’t know its name, so I call it Magic. . . . Sometimes since I’ve been in the garden I’ve looked up through the trees at the sky and I have had a strange feeling of being happy as if something were pushing and drawing in my chest and making me breathe fast. Magic is always pushing and drawing and making things out of nothing.” Although Mary and Colin do not know the name of the Creator who creates ex nihilo, they are so thankful for this magic that they desire to give voice to their gratitude. “I feel as if I want to shout out something,” says Colin, “something thankful, joyful!” Dickon teaches them the Doxology, and they praise God from whom all blessings flow. Finally, the force of love and life has been named: it is God who is the source of the beauty of nature and who evangelizes us through his creation.

As if the hymn beckons her, Mrs. Sowerby arrives unexpectedly in the garden. Motherless Colin looks at this maternal figure with a “kind of bewildered adoration and he suddenly caught hold of the fold of her blue cloak and held it fast. . . . ‘You were just what I—what I wanted,’ he said. ‘I wish you were my mother—as well as Dickon’s!’ All at once Susan Sowerby bent down and drew him with her warm arms close against the bosom under her blue cloak.” It is difficult to ignore the Marian symbolism of her blue garment and her motherly embrace. After their encounter, Mrs. Sowerby intercedes for Colin, boldly writing to Mr. Craven and urging him to come home so that he can know his son and redeem their lost relationship. He returns to see the shocking transformation of his formerly bedridden son and awakens to a new life himself. The Secret Garden speaks not only to how God evangelizes us through the works of his hands but also to how, when we embrace an attitude of childlike wonder and gratitude, we become evangelizers ourselves. We see how participation in the wonder and beauty of God’s creation is contagious. It passes from Mrs. Sowerby to her children, Martha and Dickon, who communicate the truth to Mary and Colin. From Mary and Colin, this wonder reawakens even crotchety Ben Weatherstaff and the anguished Mr. Craven to the goodness of life.

The Secret Garden is a critique of a modernist worldview that denies the truth that, as Fr. Harrison Ayre puts it, “God is able to communicate with creation through his creation.” The story reveals how God’s creation (the beauty of the earth and the communion of his creatures) can mediate his message of love to the human soul. One such moment comes when, still far away from home and drowning in depression, Mr. Craven sees a blue flower and cries, “I also feel as if—I were alive!” As with the prophet Isaiah who spoke of the mountains and hills bursting into song and the trees of the field clapping their hands (Isa. 55:12), creation calls to Mr. Craven, reminding him of who he is called to be and pushing him toward home and his son.

This lovely tale is a story of redemption. A woman’s literal fall in a garden leads to death, the severing of relationships, isolation, and an inability to see the reality of God’s enchanted world. But the site of tragedy becomes the site of grace and rebirth. The garden is where the children awaken to a much truer story than what they once believed. At first, Mary and Colin’s narrative was set in a cold world of monotony, where they were alone and unwanted. In the garden, they discover that they are precious, beloved, and walk on an earth full to bursting with the Love that gives life to all things. Mary and Colin learn to see the world sacramentally, as the Sowerbys see it, as a love letter from the God of the universe calling them to awaken to abundant life—a song that beckons us also to turn with grateful hearts to the Creator of tulips, roses, friendly robins, and even ornery children. If we are to walk like children of the light then, along with Colin when he first hears “Praise God from whom all blessings flow,” we, too, should cry out, “I want to sing it, too. It’s my song. How does it begin?”

As Pope Francis reminds us in his encyclical Laudato Si,’ “Rather than a problem to be solved, the world is a joyful mystery to be contemplated with gladness and praise.” The Sowerbys, Colin, and Mary show us how to live out this mystery. In The Secret Garden, we see the powerful effect of a human being fully alive. What kind of story could be more valuable, whether we are ten years old or one hundred?