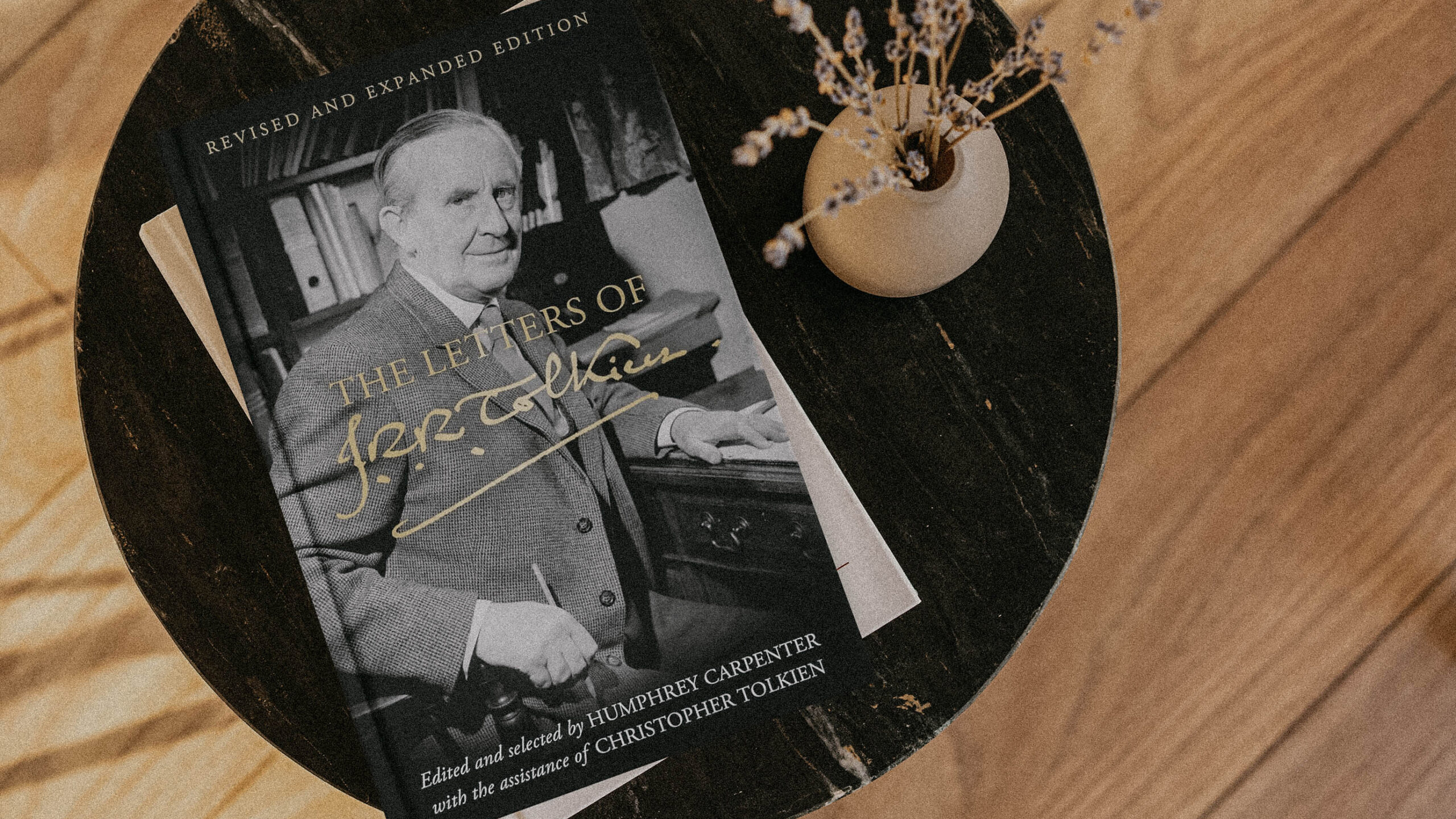

J.R.R. Tolkien is not only justly famous as the author of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, and indeed as the creator of the entire richly detailed legendarium of Middle-earth, he also deserves fame as a great writer of letters. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, first published in 1981, only eight years after his death, has become an indispensable resource for anyone seeking to understand him and his work more fully. His letters are also an absolute delight to read, giving a sense of Tolkien’s personality, his wit, his faith, and his humanity. It is therefore a matter for rejoicing that, in this year of the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death, an Expanded and Revised Edition of the Letters has been released.

It is, of course, still a selected letters, not a complete collection by any means, but the new edition lives up to its “expanded” title. It contains 154 entirely new letters, bringing the total to 508. Helpfully, the new letters have been inserted in the correct chronological order, but with alphanumeric references so that the original numbering of the letters is preserved. So, for instance, Letter 38 to Stanley Unwin (from the first edition) is now followed by Letter 38a to Michael Tolkien (a new letter). In addition to these new letters, material has been restored to forty-five of the letters already included. Interested readers can find a helpful overview in the Guide to Carpenter’s Revised Tolkien Letters Changes found at the Tolkien Collector’s Guide website, which also has a very useful database with information about all of Tolkien’s letters (published and unpublished).

The Expanded and Revised Edition provides significant new material that shows how integrated his faith was into his daily spiritual life, in a variety of ways, often in small but significant details.

As we learn in the foreword, the 2023 edition consists of the manuscript as the editor of the original 1981 volume, Humphrey Carpenter with the assistance of Christopher Tolkien, submitted it to the publisher, Rayner Unwin. However, Unwin felt that the selection was too long to be able to publish in an affordable edition at that time, and so Carpenter abridged it, cutting about 50,000 words. It is this material which has now been restored.

One of the effects of the restored material is to help make the Letters a more well-rounded portrait of Tolkien as a man. The 1981 edition was focused (and, as we now know, pruned) in such a way that it placed an emphasis on Tolkien’s work on The Lord of the Rings: its writing, preparation for publication, and reception. The wider sampling of correspondents and the more varied content now gives a fuller and richer view of his friendships and professional relationships.

One of the highlights of the expanded edition is that we have many more letters to his children, from 1934 onward; the Tolkien Collector’s Guide notes in its statistical overview of the new edition that 40% of the new letters are to family members. These family letters are a delight, giving a real sense of Tolkien as a father, an aspect of his character that those who knew him well considered of the greatest importance. Simonne D’Ardenne, who became an ‘unofficial aunt’ while staying with the Tolkiens for a time and was a lifelong friend and correspondent of Tolkien, observed that “Among the different aspects of Tolkien’s humanity, there is one which deserves special attention, that of paterfamilias. All his letters, extending over about forty years, tell of his concern about his children’s health, their comfort, their future; how best he could help them to succeed in life, and how to make their lives as perfect as possible.”1

Naturally, having drawn on the 1981 Letters in my research for Tolkien’s Faith: A Spiritual Biography, I was eager to see what new insights might be found in this edition, and I was not disappointed. The Expanded and Revised Edition provides significant new material that shows how integrated his faith was into his daily spiritual life, in a variety of ways, often in small but significant details. For instance, the Expanded Letters has more than thirty instances of him writing “God bless you,” over against only nine in the 1981 edition. We can now see for ourselves what Clyde Kilby meant when he observed that Tolkien would reference his faith very naturally in conversation: “he would just fling out these things: talking on the phone with a priest friend, I heard him say at the end of a conversation, ‘Well, may the Lord bless you’ in the most sincere feeling tone.”2

I found one restored passage particularly moving. We now have the original opening of Letter 54, which in the 1981 edition begins with “Remember your guardian angel.” Tolkien, writing to his son Christopher who is serving in the Second World War, gives advice that shows how his faith was deeply felt and integral to his life:

I hope conditions and life are bearable. I am afraid there is nothing now left for the pater to do for you, beside pray for you. God bless you. Don’t forget, all the same, that I am always at your service for such advice, or comfort, as can be sent by letter; and for any matter in which my exertions or small influence can help you at all. At the moment, I have no advice to give except to practise your religion as well as you can: taking every opportunity of the sacraments (esp. Confession) and pray. Pray on your feet, in cars, in blank moments of boredom. Not only petitionary prayer. But remember me: I have a good many difficulties to face.

This considerably larger selection allows us to hear Tolkien’s voice more fully and with greater depth and nuance.

There is so much fascinating material in the new Letters that it would be all too easy to allow this first look to become an epic. Here are just a few samples from the new material that struck me as particularly interesting, amusing, or illuminating:

Letter 80a, to G.E. Selby, 19 September 1944, congratulating him on the birth of his daughter: “There is something peculiarly gracious and empriding (to coin a word) about being the father of a daughter. I had to wait a good while for mine, fourth after three sons.”

Letter 91c, to Christopher Tolkien, 10 December 1944: “I gave myself a pre-Xmas gift in the shape of a pole-pruner – a 12 foot scarlet lance with a hook at top and a pruning knife worked by a handle at bottom. I must have looked a bit odd cycling back from Goundrey’s in my garden clothes (both knees out and insuff. screened by an old overcoat) with my red spear at rest. In a swish of wind I only just missed unhorsing Mrs Barrington-Ward as she ground along on her ancient bicycle.”

Letter 144a, to P.H. Newby, BBC, 3 May 1954, about a possible BBC Radio talk on the eighteenth-century Grammarians: “I am sure there is matter for a broadcast-talk on the subject which you mention, as long as you and anybody who talks remember the fact, pointed out by Bernard Shaw, that odium philologicum is more bitter than odium theologicum, and that a murderous spirit may well be aroused by any controversy about English grammar or usage. All the more fun.”

Letter 196a, to Michael George Tolkien, 24 April 1957, giving some advice to his grandson in his academic studies: “However, there are too many absorbing things in the world. One has to choose and stick to a few.”

Letter 242a, to Austin and Katharine Farrer, 16 December 1962: “Perhaps I may say also now (as I have meant to do for some time) that though I only briefly thanked Austin for his booklet on the Rosary (I hope I did!), I have now had it by me for a long time, and have derived profit and encouragement from it. I was late in finding the Rosary, and it has been in addition a great delight to know that others whose virtue and learning is far above mine are companions. I began to use it only after hearing [Ronald] Knox (on a private occasion) say: ‘Personally I do not like the Rosary, but I have a suspicion that Our Lady does.’ Very Knox. But obedience to one’s Mother is only a beginning! It can be greatly rewarded.”

Letter 331a, a reply to a letter from a psychiatric patient in Broadmoor Hospital, December 1971: “I am so glad that you have read my book again, and have liked some of the poems; and also that you are feeling better. The ‘hobbits’ of course were meant by me to be just ordinary kindly human people, fond of food, and fun, small in size but strong and brave and very good at driving away all nasty creatures and at helping other people that were troubled by such things. . . . If you want to, or wish to have anything explained, write again. It is, I am afraid, too late now for this to reach you at Christmas, but I hope you had some of the love and peace which you kindly wished me to have.”

Tolkien’s daughter, Priscilla, was of the opinion that Tolkien’s letters are of great interest because they offer “an authentic means of understanding” an author; indeed, “his letters are his authentic, conscious voice.”3 This considerably larger selection allows us to hear Tolkien’s voice more fully and with greater depth and nuance. The Letters have always been a treasure trove, now with even more treasure to be found.

1 S.T.R.O. [Simonne] d’Ardenne, “The Man and the Scholar,” in J.R.R. Tolkien: Scholar and Storyteller. Essays in Memoriam. Ed. Mary Salu and Robert T. Farrell. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979. 33.

2 Clyde Kilby, “Dr Clyde S. Kilby Recalls The Inklings,” Notes from an interview with Michael Foster, October 10, 1980. Marquette University Department of Special Collections and University Archives. 4–5.

3 Priscilla Tolkien, “The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien.” Talk given to the Oxford University C.S. Lewis Society, April 30, 1991.