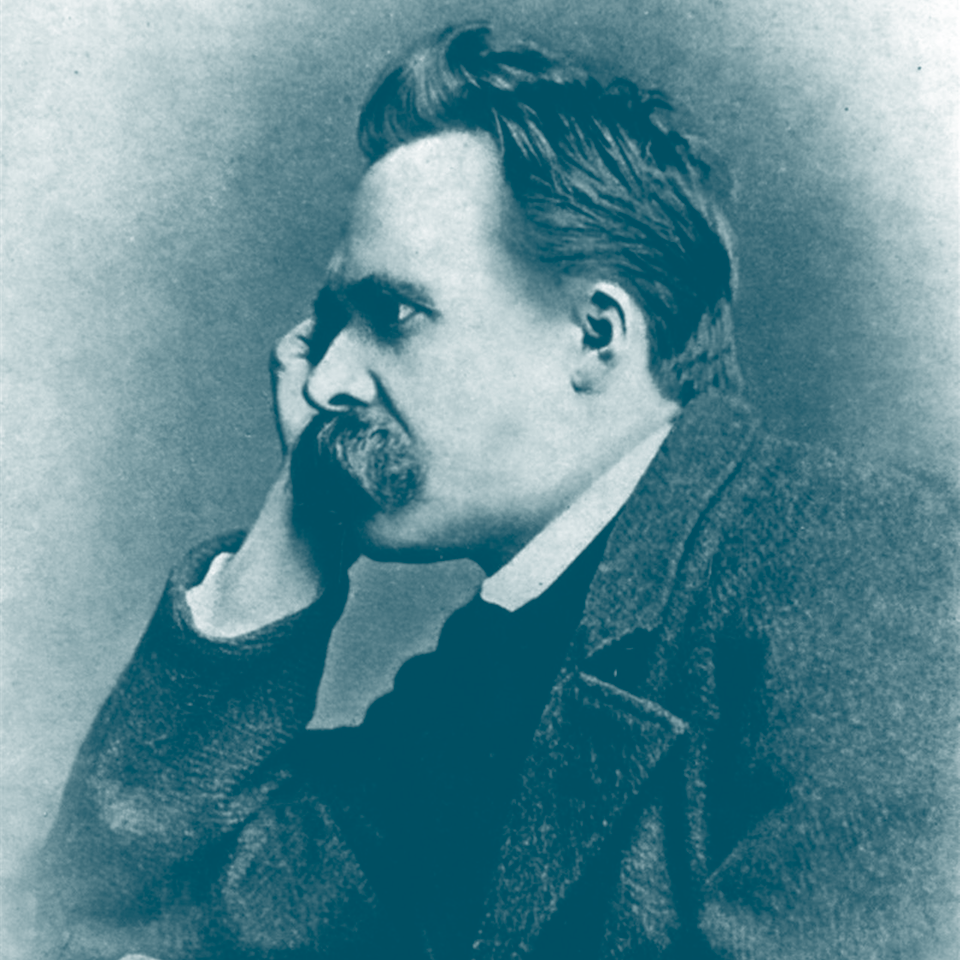

In the first part of our interview, Dr. Grant Kaplan introduced René Girard and the basics of his theory of mimetic desire. In this last part of the interview, Dr. Kaplan explains why Girard’s analysis is apologetically useful and similar to some insights made by modern figures like Nietzsche and Freud.

Robert Mixa: Besides Freud, who else influenced Girard?

Grant Kaplan: Nietzsche. Nietzsche sees the situation very clearly. He cannot stand what he sees, and so when he talks about the priest, he will talk about the priest in this very nasty way and say the priest is this “vampire” of society.

The challenge is to go through the exercise. Imagine you have two primitive societies with equal access to natural resources. They have the same access to water, food, etc. Imagine that one society is going to be areligious. They are going to say, “We have nothing to do with religion. We are just going to work; we are going to build our stuff; we are going to hunt; we are going to farm; etc.”

The other society is going to be religious. They say, “We are going to take this 10% of the population; they are not going to work; they are going to tell us that we need to hand in this portion of our animal-kills or our grain, and it is going to be burned.” Just completely burned up and used for a ceremonial ritual to keep it raining or something like this.

Now, maybe the priest class can fool people for a while; people get caught up in it. But at the end of the day, if you have these two societies next to one another, it seems like the nonreligious society would flourish. You would think that the nonreligious society would be the more advantageous one. Nietzsche cannot stand priests, but he knows they are there in history. But why are they there? Girard notices every human society, every ancient culture we know, has something like religion. Why? Wouldn’t it be disadvantageous to have religion?

Now, someone like Richard Dawkins will compare this to moths and their evolutionary short circuit. They fly toward the nocturnal light, which for the most part was the moon. That is why they fly to the lamp and kill themselves. It seems like a suicide mission. He wants religion to be something like that. It is just something we are genetically wired for, this belief in God. Maybe it was of use when people were scared and huddled in caves 10,000 years ago, but it is just not of any purpose now.

But these side explanations are nuts! The fundamental task for Girard is to be able to explain why religion emerges. Why religion not only survives but thrives in all these ways. Think about the Egyptians and their pyramids. Well, these are just elaborate crypts for the dead. It is all just about burying the dead. Or think about Aztec society. They expended tremendous energy to hunt people down so they could take their hearts and offer them up to the sun so the sun god did not turn the lights off on them.

On its face, it just seems like so much of religion is unproductive. Girard says maybe there is something useful in religion, and we must try to figure out what it is. He thinks the scapegoat mechanism is that thing.

Then he gets to the Bible. He was raised Catholic. He said he basically stopped going to church the first chance he could. He was born on Christmas Day, 1923, to a typical French family. At the time, for an upper-middle-class family, it was normal for the mom to be religious and the dad to be secular. That is what his family was.

His mother was a pious lady, but he basically stopped going to church. He had all the suspicions about Christianity. When he initially considered the Bible, he thought it was like these ancient myths: full of violence, a God that seems to be vengeful (and that it is just one more myth).

But the problem he noticed is that Christians do not want to see any similarity between the Bible and myths. The problem with seculars is that they just want to see them as identical: “You have got this resurrected victim, right? This is a common mythical theme, a resurrected victim. That is what Jesus is.”

Curiously, Nietzsche—and Girard makes a big deal out of this—sees that it is the interpretation that matters. Dionysus and Christ are both victims of mob violence. But Christians interpret it in a certain way. This is what Girard picks up on. He says from the Abel story onward the stories are told not from the perspective of the perpetrators who commit violence against the victims, but they are told from the perspective of the victims.

You see these classic victims. You see Job, classic victim. Joseph, another classic victim. Compare them to Oedipus, right? Oedipus and Job have a lot in common. But how are they interpreted differently?

Let us go back to Sophocles. What starts the whole thing? It is like the first murder mystery. Everyone is dying in Thebes. There is a plague. No one knows what is going on. “Someone must have committed a religious transgression!” Oedipus, the king, says, “Let us go find this person. Let us find him!” It turns out that it’s him. But what is the crime? Well, he kills his father and sleeps with his mother. Two big no-nos, right?

Now, go back to Genesis. What is Joseph’s problem? Well, he annoys all of his brothers so he gets sent there. Then he is in Egypt and what is he accused of? Well, not sleeping with his mother but sleeping with the wrong person. He is an outsider. Oedipus, classic victim. He walks with a limp, so he is a classic sign of a victim in ancient literature and myth.

RM: He is a victim in our interpretation, right?

GK: Yes. We would say, “So what if he killed his father and slept with his mother. It has nothing to do with the plague!” But for the Thebans, it absolutely did. “Even if Oedipus is guilty, he is still innocent”—that’s what we would say, right? And so with Job. Somehow he got too cocky or whatever it was. But there is a key line in there where he basically says, “No, this is not true. This is not really the case. I do not deserve this!” With Joseph, it is of course a classic story, but it has this twist. Girard thinks it was originally a myth and then it became part of biblical revelation. You get God on the side of the victims in the Old Testament, and then you have God identified with the victim in the New Testament.

Jesus knows exactly what is going on and he is a victim of these forces all working together. And then he is telling everybody this is what is going on, but nobody gets it; they are blind to it, and then they recognize it afterward.

RM: Is this recognition novel?

GK: This is such a radical break from the pattern of archaic religion that it is almost like a new way of thinking about religion. It is the reversal of everything about religion. In a way, you can read biblical religion as a kind of anti-religion. It is against all the things that had been built up. In the archaic religions, it is always somebody else’s fault: “God is on our side, they are the problem; if we can get rid of them then we can have peace again”—all of our peace is built upon this victim.

Again, look at some parallels. Rome was founded with the murder of Remus. And then you get the same thing with Cain and Abel—but there is a difference. In one, the violence is justified; in the other, it is God—“your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground!” (Gen. 4:10)—who is not going to forget the victim. For Girard, this changes everything. The Gospel changes everything. The Resurrection changes everything. It puts us on a totally different course.

RM: But what happens to human society once the scapegoat mechanism is unveiled?

GK: This is the real crisis and this is why Girard can say some things that sound negative and dark and apocalyptic and not very hopeful.

RM: He sure sounds that way in his interview Battling to The End.

GK: Yeah, you see that pessimism in there. The thing with the scapegoating cultures is that it works, but only for as long as people do not know that that is what is happening. But once you actually say what you are doing here—“You are just making me out to be a scapegoat but you are still going to be stuck with yourselves and I am not the fault of everything here”—once that can be said and people believe it, then it takes out the power.

You need to believe in it. That is what that story “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson is about. People have been going back to it: The New Yorker republished it and Thomas Chatterton Williams wrote an essay where he starts talking about it and how every day on Twitter there is a lottery and you just hope you are not the one. That is what it is.

But when Jackson wrote that story people were outraged. Hundreds of people canceled their subscription, thinking, “This is just a sick story!” But it is basically about mob violence, in which people think it works. Otherwise it does not work.

For those ancient religions, it works. But it is built on a lie. What the biblical religion does is it pulls the curtain back on all of this violence. Just read Matthew 23 to see how God is on the side of the victims.

RM: Is that pulling back of the curtain? Is that revelation for him?

GK: Yes. Here is Matthew 23: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, you hypocrites. You build the tombs of the prophets and adorn the memorials of the righteous, and you say, ‘If we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have joined them in shedding the prophets’ blood.’ Thus you bear witness against yourselves that you are the children of those who murdered the prophets; now fill up what your ancestors measured out!” But of course they would have. It is what they did! Girard’s analysis of that passage, when I read it, just blew me away and I continue to go back to it.

Christianity, it opens up this possibility. But then the thing is, do we really want to be this way, and for Christ to be the one we imitate? Paul says, “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1). There you get your passage of imitation. That means that there is another way. The other way is the path of reconciliation. It is a path of recognizing ourselves as sinners. . . . One disciple denies him, one betrays him, and the others (except John) basically just run away and hide. And then, when the risen Christ is revealed to them, first they are kind of scared. Then they realize they are are invited to become a community of forgivers, of forgiven ones. We are sinners who have been forgiven. That is the good news.

RM: In the Gospel of John, the resurrected Christ says to his disciples, “Peace be with you.” And then he showed them his wounds. It is beautiful that in knowing we’re sinners we find peace.

GK: We are sinners. It is usually not very pretty. And then you have a community of people who do not think they are sinful at all, which is actually what enables them to commit a bunch of sins because they say, “Those are the bad people. We are not bad, we are good people, right?”

The Church is really a community of sinners who are conscious of being sinners. They come to this awareness of being forgiven, and if you are forgiven then you are able to forgive another more easily.

If you think you have never done anything wrong, then the problem is always going to be the wrongdoers: “Everything was going perfectly, but this person started smoking cigarettes, or put a liquor store in the neighborhood”—or something like that—“We were all good and then they ruined it.”

We love those narratives—but that is just not Christian. It is not a Christian consciousness. We are aware that we are sinners, and then that we are forgiven. The Church is that particular kind of community that practices habits of reconciliation. It figures out ways to nonviolently deal with problems and allows people to become reconciled to one another and to God—nonviolently, peacefully. I would say that the great religious traditions do this. They have figured out this part of it. But the problem is that it is dangerous.

We have seen occasions in the history of Christianity when Christians turned back to the ways of the archaic religions: witch hunts, the persecution of Jews, and these sorts of things. We see it in milder ways with communities that seem to think, “Well, we are the ones who show up and our shirts are tucked in and our hair looks nice and we do not have dirt under our nails. We’re the decent and good Christian community. And then there are those dregs out there.”

James Joyce famously said the Catholic Church is basically like “here comes everyone.” In different ways, we have been unable to live up to it. It is a lot to live up to, and we cannot do it just on our own, pulling ourselves up by our own bootstraps. But only through good habits and liturgies of reconciliation and forgiveness. This is what the sacraments are about. Think about what Baptism is doing, what the Eucharist is doing, how we are recalling this violent event that we actually took part in. And then we think we are giving something to God at the beginning of the Eucharistic Prayer, but God is actually giving something to us.

RM: The first step of acknowledging ourselves as sinners in Mass seems to be congruent with Girard’s theory of conversion.

GK: I think the sacraments are built around what the Christian life is supposed to look like—that we learn how to imitate one another peacefully. Think about the lives of the saints: it is a chain of people who have figured it out and provide a model for us. It is not that we are supposed to somehow be John of the Cross or Teresa of Avila, but that we are supposed to be ourselves, but be ourselves in such a way that we imitate their holiness and grow closer to Christ. And then that brings us to a Christ-consciousness, an awareness of sin.

RM: Why do you bring Girard and philosopher Charles Taylor together in your book?

GK: Taylor and Girard basically both agree with what Karl Jaspers called pre-axial religion. For Girard, it is basically just archaic religion. Then you push through to the axial age, which is prophetic Judaism, the Vedas, some of the Chinese religious breakthroughs, and Greek philosophy, where you just have this idea of the Good. It is not the good of our particular thing but just the Good. Taylor says a story like the good Samaritan is unimaginable in a pre-axial culture. But in an axial age you can see that the good for the stranger is just a good. “Here is something beyond my tribe.”

Girard would not necessarily call it pre-axial. Actually he would say something like archaic and then biblical religion, and then Taylor sees the “secular age” as the third great religious atmosphere or revolution. It is called the axial age precisely because it is an axis, it flips. But the secular is an iteration of this Christian point of view, this Christian culture. Girard would see it the same way, that these secular values are basically Christian values: human rights, dignity of the individual, these sorts of things. They are Christian values that come out of a Christian moral grammar, even if you wouldn’t use that particular language. There is a sense of concern for the victim.

But can human society really survive in such a situation? If you drop humility and awareness that you are part of the problem and the understanding of your own sinfulness—that the sinfulness isn’t just bad acts that you do but it is an inherited thing, that is both social and individual—and then believe that, then based just on your own actions you are probably not going to be good, so you need God’s grace.

If you get rid of all that stuff, then what are you going to get? Girard says it pretty clearly in I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. He calls it, I think, a hyper-Christianity where it is just people trying to out-victimize one another. It is basically saying, “I am the real victim here”—“No, I am the real victim here—“Well, this person’s the victim”— and so on.

RM: So now the victim has power?

GK: You get people wanting to claim the mantle of victimhood because it has a kind of moral status. The crazy thing is that the right and the left both do this. They both do this obsessively in terms of victim status.

Now, the people whom the right exalts as victims are different than the people whom the left exalts as victims. And then different media pundits are effective to the degrees to which they can make arguments that convince enough people that no, this is the real victim here. It just becomes a game of trying to out-victimize one another. The irony of the whole thing is that most human societies and cultures throughout history have not cared about victims. They are not remotely concerned with the victim. For most of human history, the thought has gone, “If you are a victim, it is because you deserve it.”

Only biblical society says that the victim has a value status. You have got this irony of contemporary atheism, a kind of moral atheism, that says, “I could never be a Christian because there is persecution of Jews and women and the Inquisition,” and all that stuff. “I do not want to be a Christian because Christianity is not for the victim enough.” But what they are ultimately saying is: “I want to be more for the victim than the religion that says God is identified with the victim.”

Now, yes, some people want just robust apologetics asserting that Christianity has never done anything wrong and defending every Christian action throughout history as good. Or as simply a kind of victorious Christianity. You just have a “God-on-our-side apologetics.”

And then you get the apologetic that says, “We can defeat them.” We have analytic philosophers who are Christian and can come up with a better proof of God and so we will get an airtight, logical argument. We will go back to Anselm or whatever it is. That sort of philosophical apologetics is, I think, a much less harmful version.

The Girardian apologetic is not as linear. It is not quite as direct and pugilistic. But I think it is the best response. I think Karl Rahner said in the 1950s, “The Christian of the future will either be a mystic or he will not exist at all.” Fifty years later, we can possibly say, “The Christian of the future will either be Girardian or will not be one at all.”

Now, that is an outrageous statement. You do not need to be a Girardian to be a Christian. But I do think that he holds the most promising apologetic for Christians in that he understands what Christianity is—and Charles Taylor’s very good at this too—and he understands its role in the historical development of religion.

It is not just these things that you memorize for catechism, but it is understanding how it radically overturns everything. Flannery O’Connor has that line from “The Misfit”: “Jesus thrown everything off balance.” That is right. I think that the apologetic value of Girard is just phenomenal and needs to be read by as many catechists as possible to get the right kind of approach.